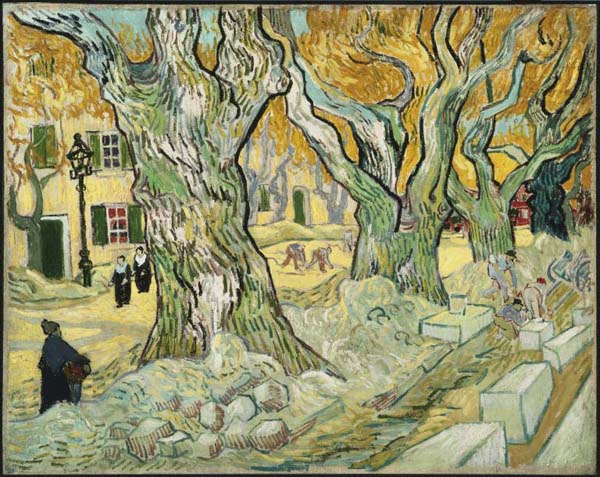

Vincent van Gogh, The Road Menders, 1889. Oil on canvas, 29 x 36 1/2 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1949.

This is the succinct title of Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith’s biography of the iconic Dutchman (Random House, 2011). The title is the only thing succinct about this thoroughly detailed and well-researched 953-page tome. Unlike generations of publications probing the artist’s posthumous fame, what artistic movement he should be associated with, and his work’s meaning, The Life focuses on Vincent van Gogh’s life and times.

Naifeh and Smith, acclaimed for their 1991 biography about Jackson Pollock, have again produced a myth-busting account of an artist who lived hard, died young, and suffered for his art. Readers suffer with him as the biography so completely documents van Gogh’s many disappointments and the guilt and remorse he felt towards his family. The authors demonstrate greatest empathy for van Gogh’s family, especially his younger brother Theo. They make the case that without Theo’s ongoing financial and emotional support and his strategic position as a mainstream art dealer, we would almost certainly not know of van Gogh’s art today.

The following adjectives describe Vincent’s behavior: mad, depressed, delusional, defensive, paranoid, envious, bizarre, isolated. The authors, like Vincent’s family, seem driven to their wits’ end by him, writing: “But Vincent could not be satisfied. Every attempt at appeasement was met with greater and greater provocation as he focused the anger of a lifetime on his captive captors (his parents). He saw only criticism in their gifts . . . and condescending indulgence in their courtesies.”

This is not to say that Naifeh and Smith do not appreciate van Gogh’s art—their descriptions of his work is penetrating and vivid: “From the limestone outcropping of Mont de Courdes in the east…he documented the view at his feet. Then, with an intensity and inventiveness astonishing even by Vincent’s standards, he filled the outline with an ecstasy of tiny pen strokes. No furrow, no fence picket, no stubble of wheat, no plug of grass, no matter how far away, went unrecorded by his obsessive quill . . . he transformed the map-like vista into a magical place.”

But these descriptive passages of praise are few and far between, as The Life relentlessly but compellingly accounts van Gogh’s path to tragedy. Because he was so unappreciated during his lifetime there is little to lift readers’ spirits from van Gogh’s delusional hope, grandiose plans, bitter disappointments, and paranoid denunciation of family and friends, followed by guilt stricken regret and mania. The Life concludes with a surprise: Naifeh and Smith make a strong and well documented case that van Gogh did not commit suicide.

Reading the book is a long, difficult journey, but like van Gogh’s art is a worthwhile endeavor. Even more important than knowledge and insight about the artist, the reader learns about the human spirit and how much self-destruction one can endure to follow van Gogh’s seemingly unobtainable goal during his lifetime: to be recognized as a meaningful artist.