Los Carpinteros (Marco Castillo and Dagoberto Rodríguez) is an internationally acclaimed Cuban artist collective best known for merging architecture, sculpture, design, and drawing. Through two films and a group of sculptural portraits, Los Carpinteros’s exhibiton Cuba Va!, produces a social landscape of Cuba’s modern history that has been at once utopian and dystopian. As part of the Phillips’s Intersections series, the project is on view through January 12, 2020.

In this two-part series, Senior Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Vesela Sretenović discusses Cuba Va! with the artists. Read Part I about the portraits.

Marco Castillo (left) in front of Comodato and Dagoberto Rodríguez (right) in front of Retráctil at The Phillips Collection. Photos: Carl Maynard

VESELA SRETENOVIĆ: When and how did you start to do film?

LOS CARPINTEROS: We started doing film not that long ago. Our first experience was Conga Irreverisble in 2013, an urban intervention in which performers sing and dance the Cuban traditional dance called conga but in reverse. In conga—which goes back to the festivities of black slaves—musicians lead the way while people march behind, following the rhythm of the drums. By reversing the direction and performing the dance backwards, conga became anti-conga, alluding to the concept of “(ir)reversibility” of truth practiced by many Cuban politicians and the press. We documented this performance by using a camera, and instead of making direct political commentary, we made a video that incited great fun for both the participants and the public, emphasizing joy and happiness over ideological critique.

But even before Conga, we talked a lot about doing a movie. We lived in Los Angeles for a while and learned a lot about movies. We also knew what we didn’t want—we didn’t want to do experimental movies or sound-based movies. Instead, we wanted to do a traditional linear narrative; we wanted to tell a history for people to see and to be seen. We were missing something in our art—a type of narrative that includes a human presence.

VS: But I think that all of your work has a human presence, implied through its absence. Your films are, in my opinion, not that much different than your other works—in fact, I think they are the cinematic version of them. They embody the same kind of poetic yet poignant nostalgia, but unfold differently through moving images so that the storytelling is more direct.

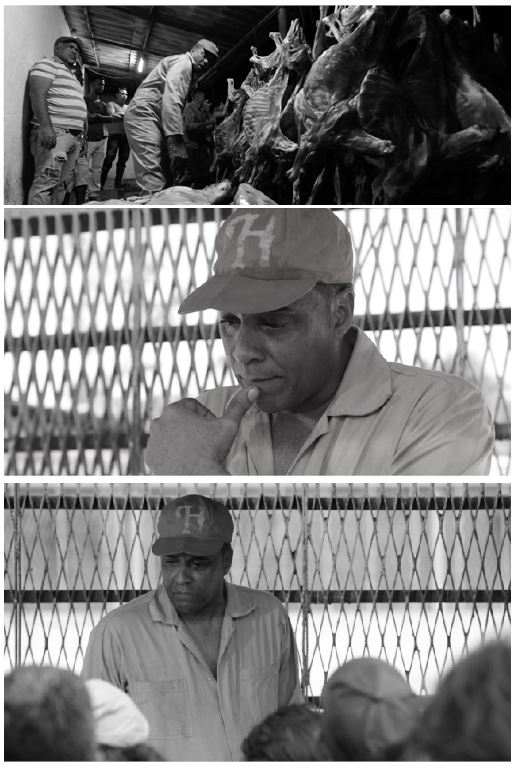

Stills from Comodato (2018). Courtesy of the artists.

LC: That’s good to know. These two films are for us travels in time. Retráctil is based on a true event from the early 1970s, the so-called “Padilla Affair,” when the book of poems by Heberto Padilla, Fuera del juego (Out of the Game) from 1968, was awarded the yearly poetry prize, only to be censored because of its so-called counterrevolutionary content. Consequently, Padilla was forced to renounce his views and publicly apologize. This was a very dramatic event; Padilla was our “Tropical Galileo,” punished in front of the public; his “apology” marked a turning or “irreversible” point in Cuban modern history—a firm disbelief in the ideals of the revolution. We edited down his four-hour speech to 17 minutes by taking some of the most important statements and hired a non-professional actor to play it. In this film, Padilla is presented as an anti-hero having to denounce everything he stood for.

The other film, Comodato, functions as the result of Retráctil—we, Cubans, didn’t become equal despite a large sacrifice. If Retráctil stands as the beginning of the end of the revolutionary ideals, Comodato bears witness to the disillusionment in so-called egalitarianism. For Comodato, we filmed at least 17 houses that detect the deep inequality, hypocrisy, and paradox of our society. It’s a silent, peopleless documentary, a monument to inequality. Cinematically speaking, both videos are rooted in a tradition of Cuban film from the 1950s and 1960s that pays respect to film noir, neorealism, and in particular to the 1964 film Soy Cuba which was done in a single shot and directed by Russian filmmaker Mikhail Kalatozov. Retráctil is black and white and was taken as a continuous shot by a single camera; Comodato has a faded-color quality and long takes. This was intentional and pays homage to previous cinematic traditions.

Stills from Retráctil (2018). Courtesy of the artists.

VS: How do you see the portraits in relation to the films?

LC: Essentially, they are all monuments. Retráctil is a monument to a loss of freedom of expression, Comodato is a monument to inequality, and the portraits are monuments to anti-heroes. They are all reflections of our life in Cuba, embodying living contradictions we have experienced. On the other hand, by showing this body of work in Washington, DC—the city of national memorials—we wanted to grapple further with the notion of the monument and emphasize its dual or reversible character: grandeur, power, heroism, but also weakness, failure, and anti-heroism.

Read Part I of the interview about the LED portraits in the exhibition.

Read the full interview in the Los Carpinteros: Cuba Va! catalogue, available in museum shop.