Director of Music Jeremy Ney on Renée Stout and the blues. Visit our Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter August 10-30 to learn more about the intersections of art and music.

“How can you capture a wail in an artwork, which is basically a silent thing?”[1] This was a question posed by artist Renée Stout in an interview from 1994 with art historian Marla C. Berns. The wail Stout refers to is the vocal and guitar sound of bluesman Robert Johnson, who was the inspiration for Stout’s 1995 installation project Dear Robert, I’ll See You at the Crossroads. In the blues folklore, Johnson was said to have sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads in exchange for becoming a virtuoso blues guitarist. Johnson’s short life (he died in 1938 at the age of 27) is full of such legends and metaphysical encounters, and his raw, soulful blues is captured on only a handful of recordings taken at the end of his life when he was a traveling musician performing in and around the Mississippi delta in the late 1930s, enduring—like so many others—the extreme trauma of segregation.

What is it about the sound of a musician like Robert Johnson that Renée Stout seeks to “capture” in “silent” art objects like paintings or sculptures? This kind of synthesis is not a question of semiotic transference between one material domain (the aural) to another (the visual), but is more about a sense of shared emotional territory, a question of affect, feeling, and mood. Music is often thought to possess the most direct and emotive effect on our senses; music is visceral, it can transform the way we feel. This is what Robert Johnson’s music does, it speaks of pain, suffering, and hardship, but also joy, hope, and creative spirit. Renée Stout describes how, “When I first listened to Robert Johnson’s music it really hit me because it was clear this man was in pain and needed to sing about it. I’ve heard other blues singers I like just as much, but his music hit me differently. It made me want to see what it was that he saw…I just have this need to ‘illustrate,’ as best I can, the music of a man that I’ve become so fascinated with.”[2]

Thinking through music—both in the way that it “hits” us and the historical associations that underline its social meaning—can help reveal rich conceptual depths in the work of an artist like Renée Stout. Stout’s visual explorations of the “blues aesthetic”[3] (a term coined by art historian Richard Powell), are inextricably linked to her parallel interest in African history and the diasporic traditions that have shaped the musical, social, and spiritual origins of the blues as the “first completely personalized form of African American music.”[4] Two works recently acquired by the Phillips exhibit Stout’s ability to recall elements of African culture, spirituality, and mysticism, and set them in dialogue with the African American experience, generating contemporary objects that are suffused with what theorist Paul Gilroy has called “diasporic intimacy.”[5]

The 2015 mixed media sculpture Elegba (Spirt of the Crossroads) invokes the complex trickster deity of West African Yoruba culture. Elegba (or Eshu or Èsú in other African cultures) is god of the crossroads, a spiritual location where an individual must confront difficult decisions in life. The crossroads metaphor simultaneously signals a site of danger or opportunity, and in West African culture Elegba was believed to hold the spiritual potential to effect change. Through ritual and divination, where music, dance, religion, and spirituality where united in an indivisible network of social practices, the Elegba deity could be drawn upon by humans to influence events in their lives and in the world. The Elegba deity features prominently in Stout’s explorations of the legend of Robert Johnson.

Renée Stout, Elegba (Spirit of the Crossroads), 2015–19 Mixed media, 39 x 17 x 13 in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of the artist and Hemphill Gallery, 2019

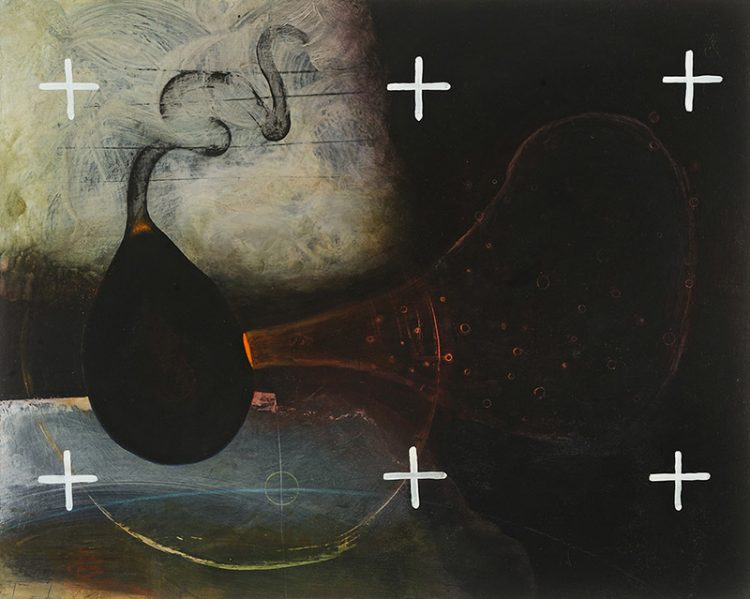

Renée Stout, Mannish Boy Arrives (for Muddy Waters), 2017, Acrylic and latex on wood panel, 16 x 20 x 1 1/2 in., The Phillips Collection, Director’s Discretionary Fund, 2018

But the powerful Elegba symbol also appears elsewhere. In Stout’s 2017 painting Mannish Boy Arrives (for Muddy Waters), the shape of the Elegba sculpture seems to manifest itself with a bright orange light that appears to signal a path forward, perhaps indicating a choice to make at the crossroads. In the song “Mannish Boy,” bluesman Muddy Waters sings, “I’m a hoochie-coochie man,” invoking a veiled double meaning: the sexually provocative 19th-century dance and the hoodoo spiritual traditions that connected enslaved Africans of the Mississippi Delta (the birthplace of both Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters) to their ancestral homeland. The “diasporic intimacy” of these traditions, as scholar George Lipsitz has observed, allowed “displaced Africans in the American South to keep alive memories of the continent they came from through a wide range of covert practices.”[6] Stout’s deployment of the Elegba icon in Mannish Boy Arrives (for Muddy Waters) is similarly covert and coded, and the image of the crossroads serves a blues-tinged metaphysics, an imagined transitional and transcultural site where African ancestry and African American experience meet. Renée Stout’s sculptures and paintings thus perform the cultural memory of the blues, conjuring a space in which an acoustic past resonates in the visual present. Far from being “silent” objects, they vibrate with sonic potential, calling out to us to look, listen, and respond.

Adapted from the forthcoming catalogue Seeing Differently: The Phillips Collects for a New Century (D Giles, 2021), published on the occasion of The Phillips Collection centennial.

[1] Quoted in in Marla C. Berns, Dear Robert, I’ll See You at the Crossroads: A Project by Renée Stout (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press), 38.

[2] Ibid.

[3] See Richard Powell in “Introduction: The Hearing Eye,” in The Hearing Eye: Jazz & Blues Influences in African American Visual Art, ed. Graham Lock and David Murray (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 4.

[4] Lawrence W. Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), 221.

[5] Paul Gilroy, Ain’t No Black in The Union Jack (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 156.

[6] George Lipsitz, “Diasporic Intimacy in the Art of Renée Stout,” in Marla C. Berns, Dear Robert, I’ll See You at the Crossroads: A Project by Renée Stout (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press), 10.