Poet Sandra Beasley at The Phillips Collection. Photo: James R. Brantley

This Thursday, poet, essayist, and translator Forrest Gander reads from his work in response to the Angels, Demons, and Savages and engages in conversation with poet Sandra Beasley as part of the Folger Shakespeare Library’s O.B. Hardison Poetry Series. In anticipation, Sandra Beasley–author of three books including I Was the Jukebox and winner of the Barnard Women Poets Prize–guest blogs about her experience of the exhibition.

One of the pleasures of growing up in the D.C.-area is a longstanding relationship with art. My old albums include crooked middle-schooler snapshots of Brancusi sculptures, the camera’s flash creating bounces of light. The Rothko Room at the Phillips became a favorite refuge ten years ago, when I first moved to a studio at 18th and S Streets, NW. So when I walked into Angels, Demons, and Savages: Pollock, Ossorio, Dubuffet and saw Jackson Pollock’s Number 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist), I grinned: There you are!

Alfonso Ossorio at the Creeks, 1952. Photograph by Hans Namuth ©1991 Hans Namuth Estate, Courtesy Center for Creative Photography. Jean Dubuffet’s Francis Ponge (noir sur fond), 1947, appears at near left; Jackson Pollock’s Number 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist) at center; and Dubuffet’s Les Petits Yeux Jaunes, 1951, at right.

Lavender Mist holds a particular place in my heart. I was so enthusiastic when I met the work at the National Gallery that I bought the print in their gift shop. But when I went to put it up in my high school locker (who needs Tiger Beat pin-ups when you have Pollock drip-paintings?), I noticed something was missing. Specifically a strip of composition along the righthand edge, cropped for the print’s dimensions, noticeable because it includes a splotch of rust-orange paint not found anywhere else on the canvas. This is the Pollock that taught me that nothing can replicate the experience of seeing art in person.

Similarly, my first exposure to Jean Dubuffet’s work also has the earmark of revelation. As a teenager visiting Paris with my family, we trekked to the Centre Pompidou, which houses Le Jardin d’Hiver (The Winter Garden). Somewhere in another album is a snapshot of my sister, hunkered down in its contoured black-and-white recesses. This was my first experience thinking of work as an immersive experience, resonant with the recent Phillips installation by Wolfgang Laib. (Wax Room is a lot more fragrant, though the Dubuffet room pipes in music.)

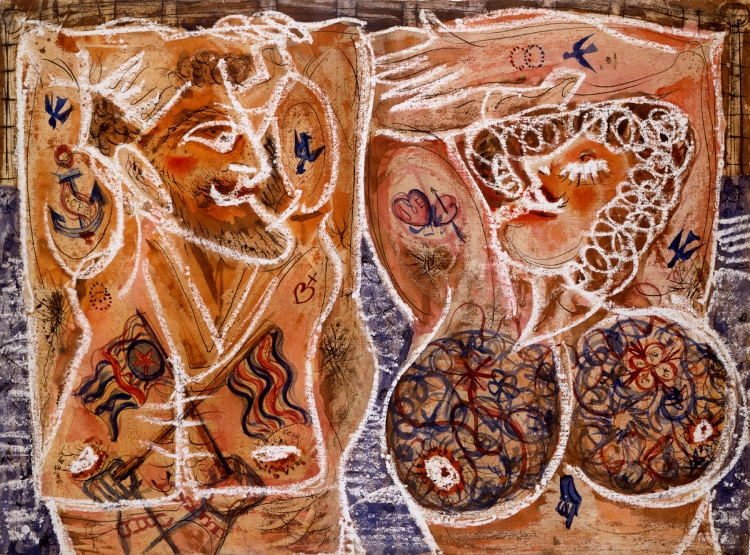

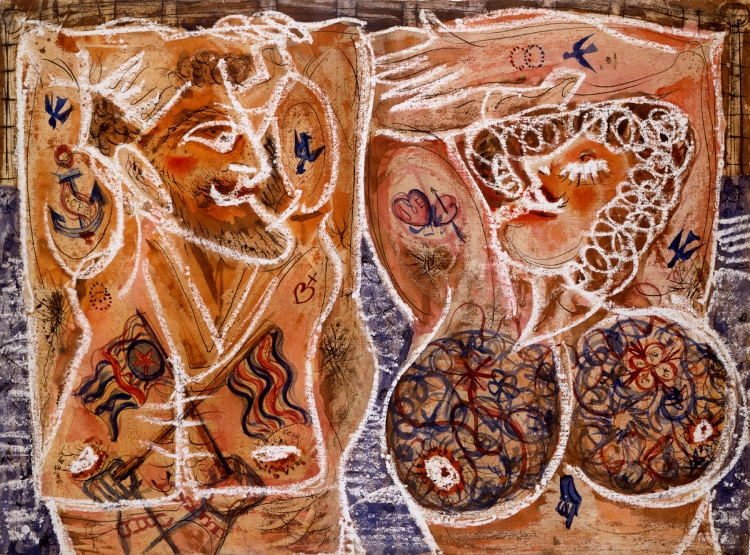

Alfonso Ossorio, Tattooed Couple, 1950. Watercolor, ink, and gouache on paper, 20 3/4 x 25 1/2 in. Collection of Michael Rosenfeld and halley k harrisburg

If Pollock and Dubuffet are old friends, then Alfonso Ossorio was a blind date. But I am moved by the intensity of his art. My admittedly biased, writerly gut tells me that Ossorio used narrative as a catalyst. He fell in love with a primary relationship, often signified in his titles (Maimed Mother and Child), and the first-level rendering was of that relationship in a suggestive sketch. This is particularly apparent when he uses wax to create a resist of white paper, as in Tattooed Couple. Then he complicates his “stories” with rich color, recursive lines, and decorative–borderline distracting–ink flourishes.

Jean Dubuffet, Corps de dame—Château d’Étoupe (Body of a Lady—Stuffed Castle), 1950. Oil on canvas, 45 3/4 x 35 3/8 in. Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio. Gift of Joseph and Enid Bissett © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

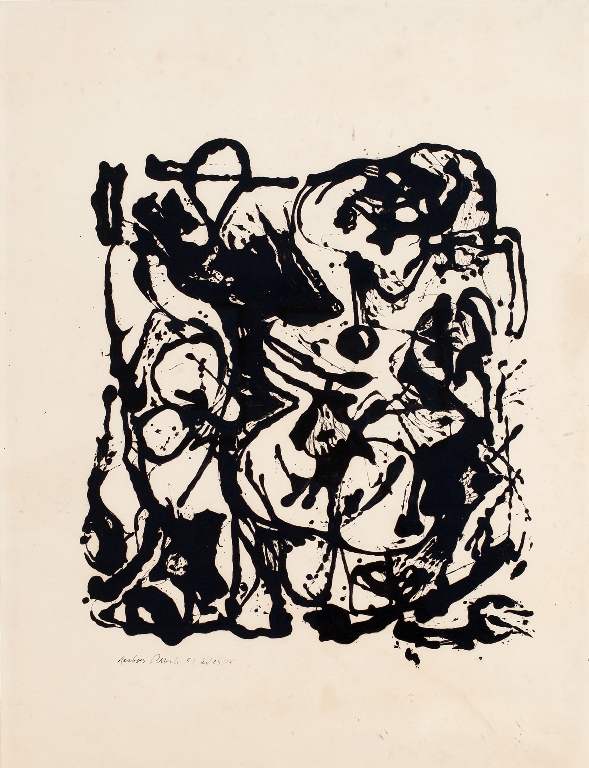

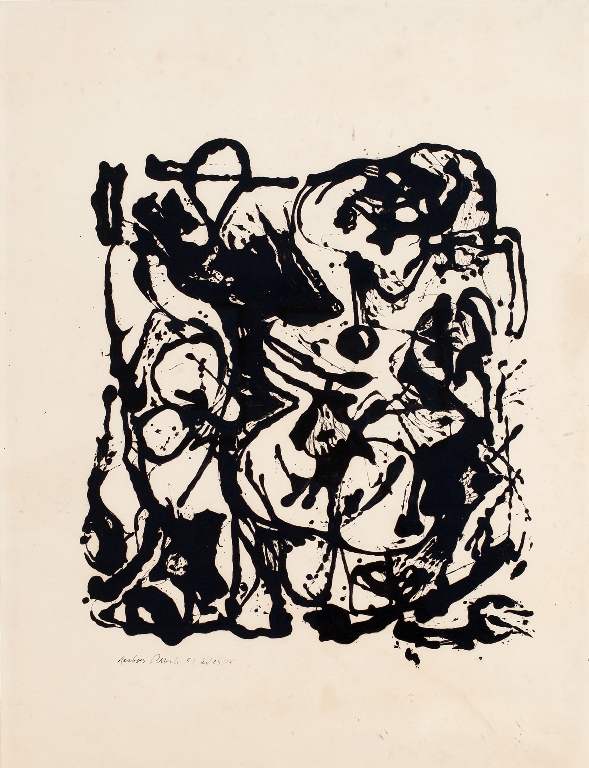

These qualities stand in contrast to Dubuffet, whose narratives often seem a later-level rendering, e.g engraving arms and pubis on an abstract shape to make it more figurative. Or for that matter, Pollock, whose works are always difficult for me to penetrate in terms of intent versus chronological process. Even with umpteen visible paint layers, they seem singular in concept. In this context, I particularly appreciate the exhibition’s attention to Pollock’s denial of “accidents” and the 1951 screen print series, composed in part in Ossorio’s studio.

The exhibition accomplishes what I consider a high goal of curation–it lets me eavesdrop on an influential conversation between artists as friends and colleagues. They did not always agree, but they did engage. The individual works are stellar. The juxtapositions are illuminating. I suspect Forrest Gander will have his own take, and I look forward to our event on Thursday. But in the meantime, I am grateful to hunker down in sheer enjoyment. And to know that next time I encounter an Ossorio, I will grin, and think: There you are.

Sandra Beasley, poet

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1951. Enamel, India ink, and graphite on paper, 29 x 22 in. Private Collection © 2012 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York