Kundiman Executive Director Cathy Linh Che and Managing Director Ryan Lee Wong come to The Phillips Collection on July 28 for The Asian American Literature Festival. As they are both festival organizers and writers, Curatorial Research Intern at the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center Carlo Tuason asked them a few questions about shaping The Asian American Literature Festival and their motivations behind getting involved.

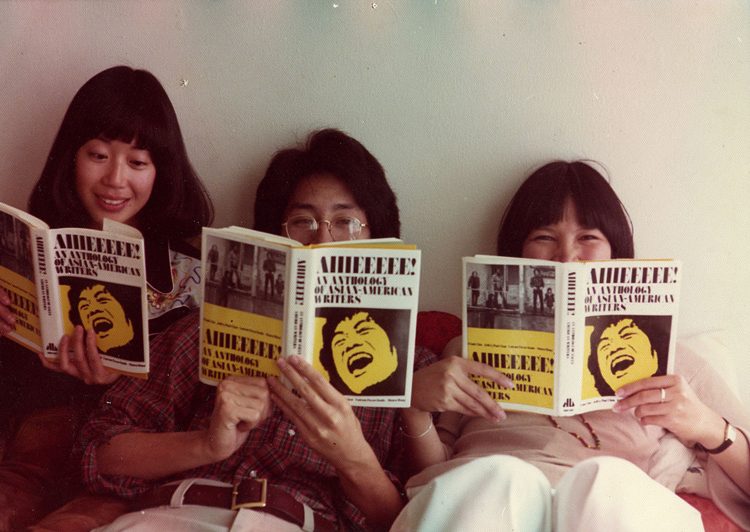

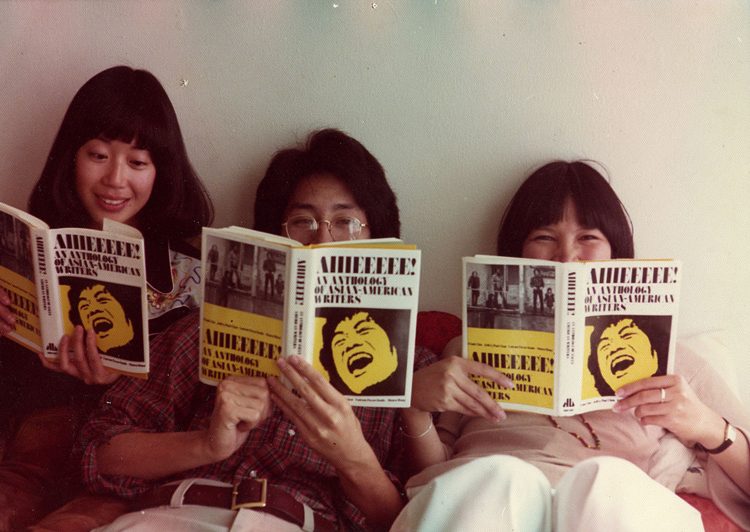

Aiieeeee! An Anthology of Asian-American Writers

What about the concept of an Asian American Literature Festival made you want to get involved? What meaning does this type of event hold to the Asian American Community?

Cathy: Kundiman is an organization dedicated to the creation, cultivation, and promotion of Asian American literature, and it seemed to me that the Asian American Literature Festival would be a groundbreaking forum for advancing this mission. I love that the event is free and open to anyone who would like to attend.

Kundiman’s programs tend to provide close up and intimate engagement, and we always are looking for ways to serve more people. In partnering with other organizations and funders, we are able to provide a larger, but still nurturing, connective space where readers and writers can co-create what Asian American Literature can be!

Ryan: A lot of my work has been around researching the origins of Asian American identity, as a strategic, coalitional movement in the 1960s and 70s. That was also the time period that gave rise to Asian American literature, with anthologies like Aiiieeeee! and cultural spaces like Basement Workshop and Kearny Street. Then there was the 90s, with Charlie Chan Is Dead and the birth of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop.

Now we’re living through a renaissance of Asian American letters, where the diversity of forms, styles, ages, histories, genre, and concerns is boundless. A festival like this, I think, acknowledges that diversity, and is less about ‘defining’ Asian American literature than offering a laboratory, a meeting space.

Roots: Asian American Movements in Los Angeles, an exhibition at the Chinese American Museum in Los Angeles, curated by Ryan Lee Wong

Ryan, as a previous museum professional, what’s the significance of holding the Asian American Literature Festival in The Phillips Collection, a museum of modern art? What implications does this have?

The Phillips prides itself, rightly, on its impressionist and modernist holdings. It’s important to remember how radical and unappreciated those styles were in their day. So the best way to converse with the Phillips is to break form, convention, and our old definitions of ‘literature’ and ‘art.’ I think it will be a very productive, funny, problematic frisson between the Renoirs and Picassos and the Asian American writers having tea, conversing in mentorships, and reading poetry in front of them. Asians in America, who were rarely seen by cultural institutions as having voices, let alone in literature, are remaking our culture by our presence there.

Kundiman Retreat, 2017

Cathy, can you share a little more about your work, particularly your poem in the most recent issue of POETRY magazine? Are there any themes in your work that you find you return to again and again?

I’m a poet, and my many communities have raised me: my family and friends, my high school teachers, undergraduate professors, my MFA program instructors and cohort, Cave Canem, Kundiman, every residency I’ve attended, every student I’ve taught. I find that what compels me most in writing are the ways that, in writing into silence, trauma, joy, the taboo, anger, we can expand possibilities of expression.

My book Split was about my parents’ experiences of the Vietnam War and about my experiences as someone who’s been hurt by sexual violence. My next book will be about my parents’ experiences as extras in the film Apocalypse Now. Here are two people who risked their lives to flee a country and a war, and while they were refugees in a camp, waiting to find a new home, were placed into the margins of their own stories.

One of the poems in the most recent issue of POETRY is about a terrible incident that happened last year with my father, and its aftermath. I can’t help but connect him to the war that shaped him for 12 years. I think that in writing these things out, we create connections, and connections reify our collective humanity—creates the possibility of belonging through understanding and perhaps even healing.

As organizers of this event, how have you seen this event transform throughout the planning process? Can you explain a little bit more about what you kept in mind when shaping and conceptualizing the Asian American Literature Festival?

Cathy: We were interested in creating spaces for emerging writers that were non-hierarchical, intimate, and participatory, so from the beginning, we programmed in late night salons, where anyone who comes can read and speak. We are also very interested in mentorship, in considering what it means to bring up the next generation of Asian American writers. We are still in progress and we are thinking through things like: How are we serving those who have the greatest need? How do we forge intergenerational bonds? How do we build meaningful mentorship relationships?

Ryan: One of the flagship programs we’re developing for the Literature Festival, in conjunction with APAC and the Asian American Literary Review, is the Mentorship for two writers with Paisley Rekdal and Alexander Chee. It’s been a wonderful process to solicit writers, read the applications, and facilitate letter writing and a reading. The mentorship fellow for Paisley, in poetry, is Justin Monson, who is currently incarcerated. We were very glad to know the call reached places that literature and mentorships often don’t. We’ve learned a lot about working with incarcerated writers—the email system, the logistical questions. Grace Lee, the fiction fellow, is also geographically separate from Alex—technology has really furthered the reach of the mentorships.

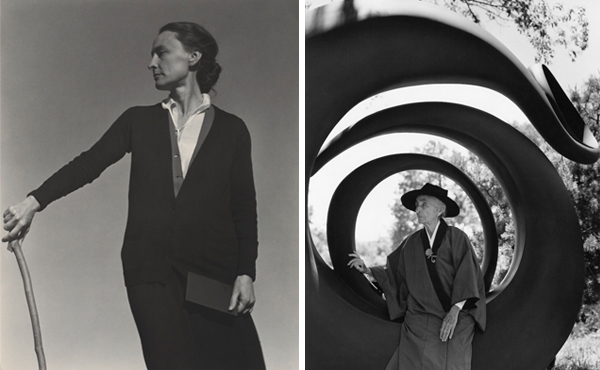

Cathy Linh Che, photo by Jess X. Chen; Ryan Lee Wong, photo by Louis Chan

What do you want attendees and participants to take away from this experience? What have you personally taken away from your experience planning this event thus far?

Ryan: I hope that younger and emerging writers in particular come away from the festival with a sense of lineage. Even today, with all the discussions around the whiteness of literature and MFAs, the great majority of writers taught and studied are white, and form is often divorced from history, politics, and identity. Of course, any study of Asian American literary history shows how capturing experiences of diaspora, writing across languages and nation, and portraying a community all require formal innovation. We have some amazing innovators like Karen Tei Yamashita and Li-Young Lee coming to the conference. One of the most powerful things we can do is converse across generations—not that we must imitate or canonize those figures. This is a chance to repair and remix our literary DNA.

Cathy: I hope that attendees come away with a sense that they have joined a community that demonstrates radical care for one another. I want folks to feel a sense of inclusion, expansion, inspiration, and a changing idea of the possibilities of what Asian American literature could mean. When we gather as Asian American writers, the quality of the conversation changes. I hope that folks come away feeling that they have agency to shape, alter, challenge, and pay homage to this idea of Asian American Literature.