This is a multi-part blog post. Read Part 1 and Part 2, and check back next week for Part 4.

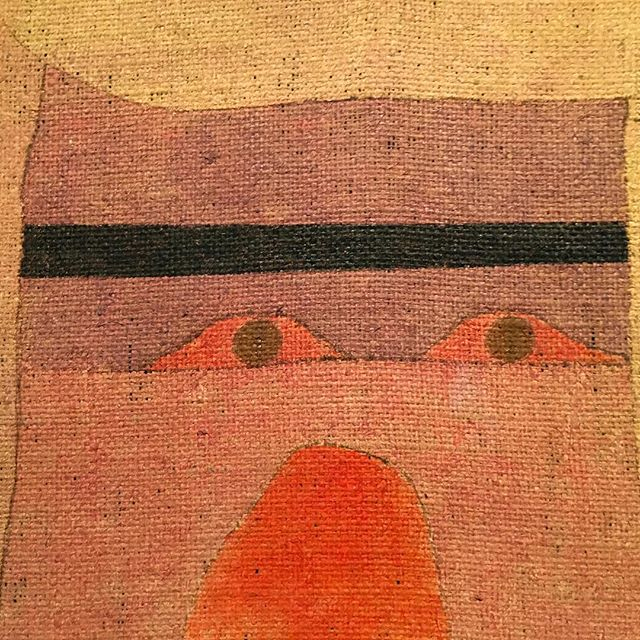

After trying my own hand at interacting with Franz Erhard Walther’s Red Song, I stood in the gallery and admired the true beauty of this piece that at first glance I hadn’t understood. Soon, two visitors, Janet and Cate, entered the gallery. After reading the Red Song text and checking which piece it was referring to, they put the provided plastic covers over their shoes and carefully walked over. As they began this process, I noticed how their body language changed. When they entered the gallery, they were confined and quiet; now they became curious, talkative, and lively, echoing my own experience. They removed the hanging items and draped them over their bodies in different fashions. Janet had turned what I thought was an apron into a cape, and Cate had taken two arm pieces and made an entire jacket. When they finished, I asked both women two questions: “what are your thoughts on interactive art?” and “what was your overall experience?”

Janet: “Interactive art is great. We (all) would like to touch more art. I didn’t understand it at first, but I don’t think you need to understand it to really enjoy it. I thought it was a great experience!”

Cate: “You are taught at an early age that a museum is a place confined by rules, but this piece is very inviting. It definitely breaks your expectation of what art is, which makes it fun. Being able to interact with it is immediate. You don’t have to think about it. It really reminded me of playing make believe, or dress up.”

I also spoke with Museum Assistant and Registrar’s Intern Jimin:

“This is interesting to see in a museum considering we have been taught to not touch the artwork. Overall I didn’t understand the subject, but I was still able to appreciate my experience with it. This whole concept is eye-catching. Once I became a part of the sculpture, I realized it’s three different pieces. Is it supposed to be one outfit worn by one person, or three different people? Why is it red? What was the artist’s intention?”

Gina Cashia, Marketing & Communications Intern