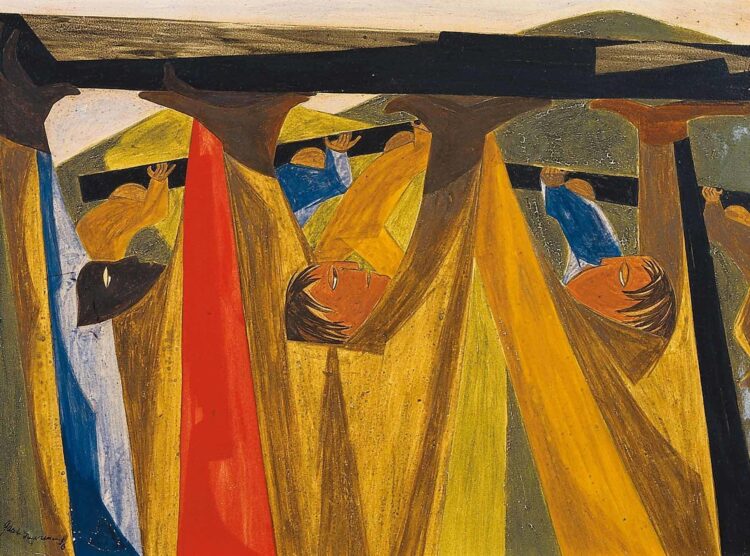

Paul Butler, The Albert Brick Professor in Law at Georgetown Law and legal analyst on MSNBC specializing in issues of race and criminal justice, penned this response to Panel 5 of Jacob Lawrence’s Struggle: From the History of the American People.

Jacob Lawrence, Panel 5, We have no property! We have no wives! No children! We have no city! No country!—petition of many slaves, 1773, 1955, from Struggle: From the History of the American People, 1954–56, Egg tempera on hardboard, 16 x 12 in., Collection of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross. © 2021 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“Jacob Lawrence was critical race theory before it was cool. Or controversial. In the Struggle series, Lawrence re-told the revolutionary part of United States history, including the saturated colors, the angles that cut, the blood. “The part the Negro has played in all these events has been greatly overlooked,” he said. “I intend to bring it out.” Especially for the children, which is why Lawrence made the images small—portable to classrooms, where they might teach a different story than the textbooks filled with the lies of the victorious.

The first glance of Panel 5 reveals something not quite legible but soaring, rising triumphant, toward a blue sky, like a stained glass window in a strange church. But it turns out you looked up because that’s where the bayonets are pointed, some of them. Other weapons are aimed by the Black enslaved and white enslavers at each other. The Black people, for once in this history, are given expression. They look angry, scared, and determined. They are dripping blood. Lawrence made the enslavers look like monsters, which of course they were. That’s why they deserved to die, Lawrence’s image shows us, their blood no more sanctified than that of the British redcoats we see vanquished in other images in the series.

The story many Americans are told about slavery includes the cotton gin, the Great Emancipator, and, lately, Juneteenth. Not so much the bloody uprisings of the enslaved. The Black American revolutionaries who Lawrence painted understood the price of liberty in a different way than Patrick Henry or Paul Revere. When and if the descendants of the enslaved obtain our freedom, the victory will owe more to the unknown Black revolutionaries than the known white ones.”

—Professor Paul Butler, Georgetown Law