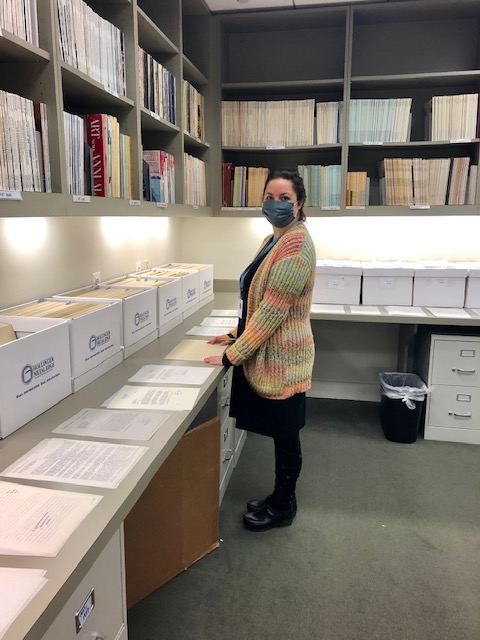

Rachel Jacobson, Digital Assets Librarian at The Phillips Collection, is managing the project and explains the process.

Digital Assets Librarian Rachel Jacobson with boxes of archival material.

There’s been a scheme going on at The Phillips Collection and we are ready to let you in! For the last few years, various staff members have been planning for an ambitious undertaking: to establish an archival digitization program for the museum’s library and archives. Although this plan has been in the works for several years, it was in October 2019 that substantial steps were taken to make this dream a reality.

In order to make sure that this project would be successful, The Phillips Collection had to prioritize the most valuable, pertinent, and relevant archival collection. The Directorial Correspondence produced by the museum’s founder, Duncan Phillips, was selected. The letters in this collection stretch from before the museum was established to Duncan Phillips’s death in 1966, when Marjorie Phillips became the director of the museum. Deciding on a collection is crucial, but it’s only a piece of the process. Next steps include planning and assessing how to get these precious documents imaged.

Juli Folk, processing archivist, alphabetizing and re-housing letters from 1955.

Keeping in mind the goals of digitization, which are accessibility and preservation, I assessed and selected a digitization vendor, Pixel Acuity.

Between March and August 2020, Juli Folk, our part-time processing archivist, and I prepared 23 boxes of archival material for Pixel Acuity. The two of us were able to start the digitization process despite complications brought on by the onset of COVID-19. The 23 boxes of material, which Pixel Acuity received and began imaging in August 2020, account for only a third of the total material being digitized. Those 23 boxes hold 3,882 archival folders, all of which have been returned, both physically and digitally, to The Phillips Collection. As of late February 2021, Pixel Acuity has 21 new boxes of material that they are working on.

Please stay tuned for more updates as this project continues.