Welcome to Phillips at Home!

I’m your host, Donna Jonte, Manager of Art and Wellness and Family Programs. I invite you and your family to spend time with works of art from The Phillips Collection, slowing down to look, think, wonder, and respond creatively.

Materials needed: A few pieces of paper (copy-paper size or larger), any drawing materials (pencil, crayon, marker, paint)

Time needed: 30-45 minutes

Designed for families with children ages 4-14

We are all in our homes and getting to know our surroundings really well. What do we learn when we compare the items on our tables with The Round Table by Georges Braque?

Let’s begin!

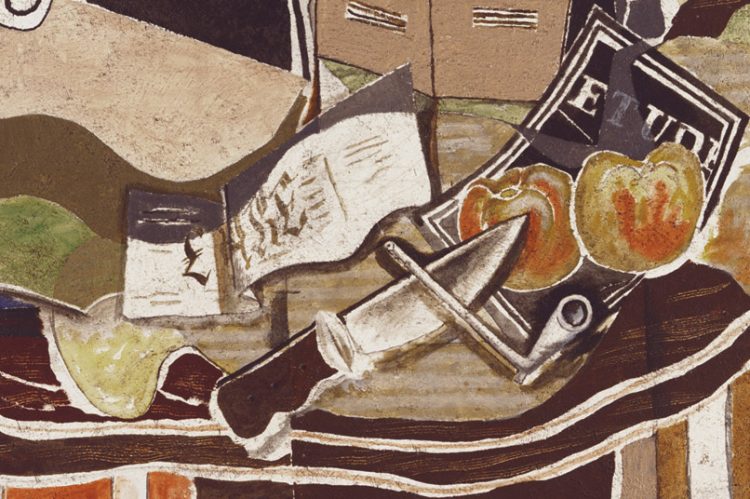

Georges Braque, The Round Table, 1929, Oil, sand, and charcoal on canvas, 57 3/8 x 44 3/4 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1934

(STEP 1) With your family, find a comfortable place to sit together to look at Georges Braque’s The Round Table.

• Look at the image of The Round Table for 7 seconds.

• Now, turn away from your computer to talk with your family. What is one detail that caught your attention? Have a brief conversation about what you think the painting is about.

• Next, take a deep breath. Exhale slowly. Are you ready to look at the image again, slowly and silently for 30 more seconds? What will you notice this time?

• Can see details clearly? The table legs, the objects on the table, the shapes on the walls, the little details at the edge of the canvas. Notice colors, lines, and shapes. This might take you an entire minute. Look slowly and carefully.

• Can you see the entire painting on your screen? Look at the composition, or how the artist has arranged the items. Notice how much space is occupied by each object. Notice where your eye goes first and how the artist guides your eye through the painting. This might take another minute or so. Thank you for looking closely. Now it’s time to talk.

• Share observations with your family. You might want to make a collective list, writing down all the details you and your family noticed. Did someone in your family notice something that you did not? We all notice different things.

• What are some of your thoughts about this painting?

• What do you think about these objects? Are they familiar to you and your family? Which ones are unfamiliar or mysterious? Which object interests you the most?

• How might these objects be connected?

• What might these objects tell us about the person who uses them?

• What do you think about the marks and shapes on the wall behind the table? How might these marks connect (visually and thematically) to the objects on the table?

• Look at the way the tabletop tips up. Why might the artist have painted it this way?

• What do you wonder about the painting? What do you wonder about the artist and his process? Ask questions! Share your questions with your family. Like artists, we are curious. Ask another question!

(STEP 2) Thank you for looking closely, thinking about what you noticed, and being curious. Before we make art, let’s learn about artist Georges Braque.

The Round Table by Georges Braque on view at The Phillips Collection in 2013

• Georges Braque (French, 1882-1962) painted The Round Table in 1929. It’s a very large painting, almost 5 feet high and 4 feet wide. Maybe it is taller than you are!

• Braque loved music as much as he loved art. He was classically trained as a musician and played the violin, flute, and accordion. He was good friends with composer Erik Satie. Do you see a piece of sheet music on the table with fancy letters that might spell “SATIE”? Do you see a musical instrument? Do you like music too?

Detail of The Round Table

• Braque experimented with art methods just as Satie experimented with musical conventions. Braque added sand to his oil paint to give texture to the surface. In some places he left the canvas unpainted.

• Braque said, “You put a blob of yellow here, and another at the further edge of the canvas: straight away a rapport is established between them. Color acts in the way that music does.” Does this statement help you see his painting in a new way?

• Braque was also good friends with Pablo Picasso; together they invented a kind of art called Cubism. They liked to paint objects from many points of view at the same time! Cubist artists like to show an object from the side, the top, the front, the back—all at once. You can see that in The Round Table in the way the table top is tipped up, showing many views of the objects.

(STEP 3) Let’s get ready to sketch items on our tables. Remember, a sketch is like a rough draft in writing—it’s a no-pressure sort of drawing.

• Find paper and a writing tool—pencil, pen, marker, color pencil, crayon. Your choice!

• Before you make your first mark, ask yourself: Are you going to create a sketch of a table top in your home that you can see at this very moment? Will you sketch from observation?

• Or will you sketch from your imagination, drawing objects that are important to you but might not be on your table at this moment? What would the objects be? A musical instrument? Your favorite snack? A board game? Your cat? You choose!

• While you draw, you might want to listen to Erik Satie’s compositions.

• When you finish your sketch, give it a title.

• Discuss with your family the objects you drew, the title you chose, and the ways that Braque’s painting inspired you.

• Notice how different your sketches are, even if you drew the same objects on the same table.

(STEP 4) Now let’s look at the work of another artist who spent time at The Phillips Collection looking closely at paintings by Georges Braque and other artists: David Driskell (American, 1931-2020).

• David Driskell’s 1966 painting of a round table might remind us of Braque’s round table. Mr. Driskell was well respected for his scholarship on African American art, his teaching, his mentorship, his promotion of younger artists, and his paintings, prints, collages, and gardens. Sadly, Mr. Driskell recently passed away. We find joy in his legacy and the important works of art he left behind.

David Driskell, Still Life with Sunset, 1966, Oil on canvas, 48 x 32 in., Collection of Joseph and Lynne Horning, on view in Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition.

• Talk to your family about how Still Life with Sunset is similar to Braque’s The Round Table. How is it different? Remember that it is important to take your time to look closely. What do you see? What do you think? What do you wonder?

• We call art works such as The Round Table and Still Life with Sunset “still life” paintings, probably because the subject of the painting doesn’t move. Often still life paintings (or sketches or drawings) show everyday objects in our homes like fruit, books, pottery, or musical instruments.

• Driskell said about his painting: “Looking back to the 1960s, I used still life subjects as an avenue to seeing a union of household objects as beautiful forms blending in with the natural world. Here, the studio extended into the exterior space of the natural world, where the sunset gave flavor to a unified composition.” Listen to him talk about this work.

(STEP 5) Let’s make art. Inspired by Driskell’s painting, create another sketch.

• If you can, use a different art tool this time. If you used crayon before, try pencil. If you used paint, use an ink pen. Artists love to experiment.

• What colors will you use? What might you put in the background? Will you add a window, connecting inside and outside, as Driskell has?

• Give your sketch a title. Put your first and second sketches side by side. Share your thoughts with your family.

• Do you think spending time with objects in your home, as we are doing now, makes them more precious to you? Are you thinking about how you are connected to the objects inside the home and to the world outside the window?

Thank you for spending time with me. I’d love to see your creations. You may email photos of your art work to me at djonte@phillipscollection.org. Observe! Imagine! Make art!

Here is some more inspiration:

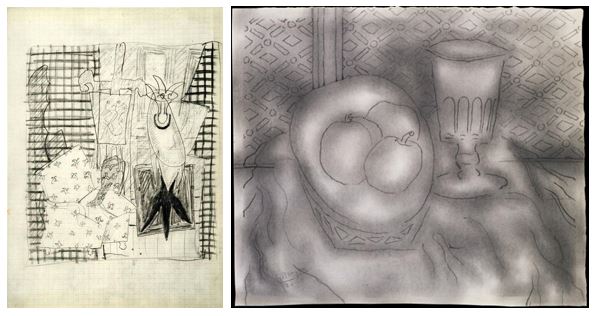

(left) Still life drawing from Georges Braque sketchbook, Archives Laurens (right) Georges Braque, Still Life, 1924, Charcoal and graphite on paper, Tate

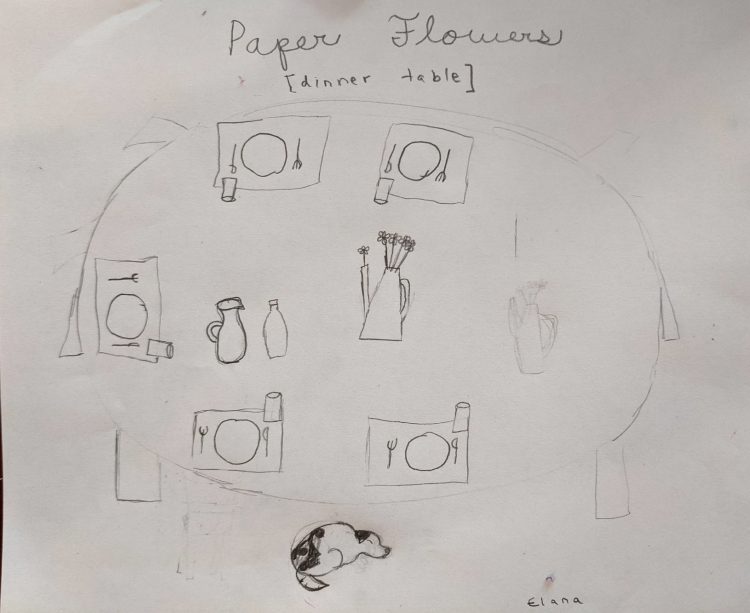

Paper Flowers: Dinner Table, by Elana, age 11, Chevy Chase, MD

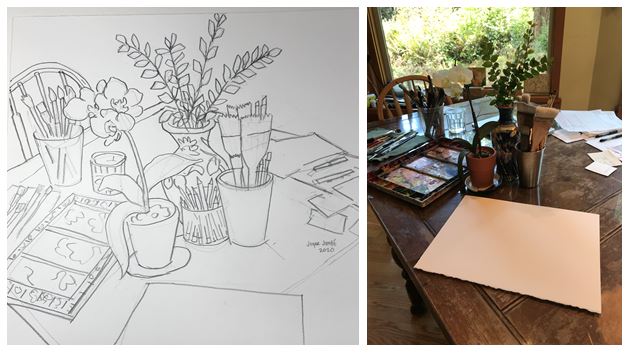

Kitchen Table, by Joyce, Arcata, CA, with photo of Joyce’s kitchen table

The guided looking sequence was adapted from Harvard’s Project Zero’s Thinking Routine “See-Think-Wonder.” Learn more about Visible Thinking Routines on the Project Zero website.