![]()

![]()

![]() Sydney Vernon: Interior Lives is currently on view at Phillips@THEARC. The Phillips Collection Fellow Arianna Adade met with the artist to talk about her practice.

Sydney Vernon: Interior Lives is currently on view at Phillips@THEARC. The Phillips Collection Fellow Arianna Adade met with the artist to talk about her practice.![]()

Sydney Vernon at her exhibition opening, Photo: AK Blythe

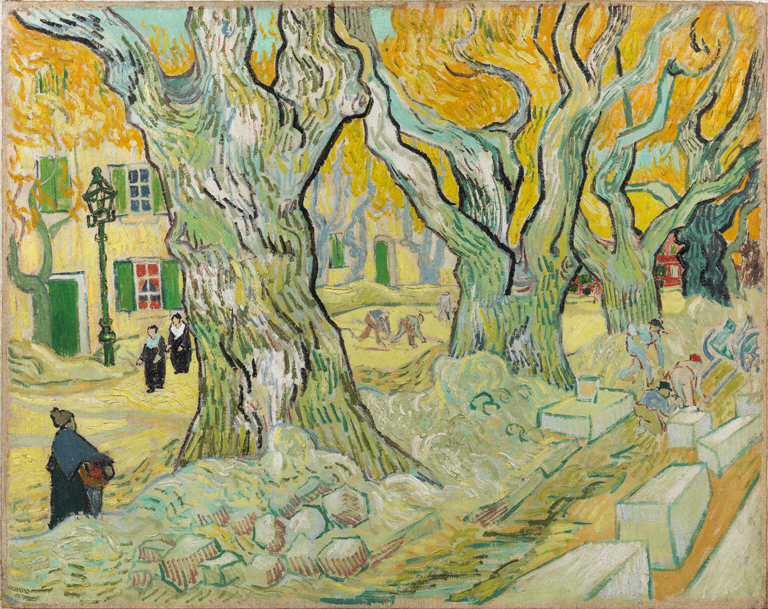

Hailing from the arts-driven Prince George’s Country, Maryland, Sydney Vernon can trace her connection to art back to her childhood. Coming from a family of diverse artists, Vernon’s path to artistry is not unexpected. From the age of four, Vernon attended Thomas G. Pullen Creative and Performing Arts School and later Suitland High School, enriching herself in an array of fine and performing arts. Vernon’s artistic talent grew with the influence of art styles such as Les Nabis and Pierre Bonnard, but her beginnings in art begin with her mother, a fashion designer. Vernon first learned to draw through fashion illustration, tracing over her mother’s drawings and designing clothing for dolls to wear.

Sydney Vernon’s mother, Photo courtesy of Sydney Vernon

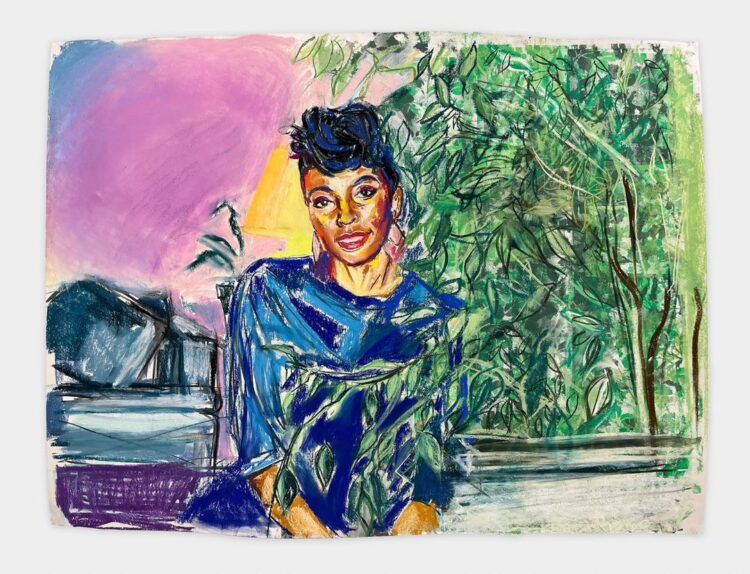

Sydney Vernon, Hide and Seek, 2024

Vernon relocated to New York at the age of 21 to pursue her bachelor’s degree at The Cooper Union. Being far from home, she used the distance as a way to explore ways to connect her artistry to her family. Over the last five years, Vernon has crafted layers to her family’s mementos, piecing together oral histories of her lineage.

Items from Sydney Vernon’s person archives, on view in the exhibition, Photo: AK Blythe

What started from a place of homesickness quickly blossomed into an intimate familial research practice. As Vernon discovered more about her family’s history and collected scans of family photos, she also reconnected with cousins, passing stories with one another.

Lugarry Vernon and Doreen Marrow, Photo Courtesy of Sydney Vernon

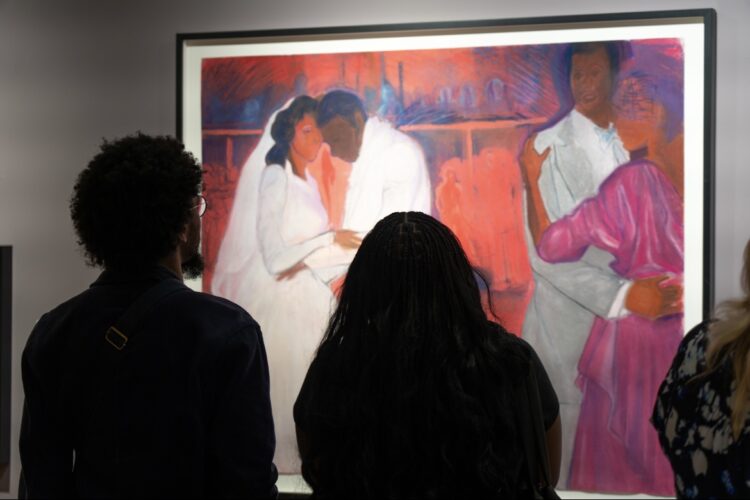

Visitors looking at Sydney Vernon’s The Real Thing Strange, 2023, at the exhibition opening. Photo: AK Blythe

Vernon’s work is distinguished by her unique approach to reinterpreting the positions and postures of the people seen in her archival family photographs. Through her creative lens, she beautifully combines personal recollections and accounts with broader historical and cultural perspectives, such as the Black femme experience. Vernon’s works show that she is not only a visual artist but also a collector of memories that span time, encouraging viewers to consider the connection between individual memory and ancestral heritage.