Explore how artists in Pour, Tear, Carve: Material Possibilities in the Collection (on view through May 14) use various materials in different ways in their art, and how their choices convey meaning to their work.

Take a look at the works below that incorporate plastic and consider:

- • What materials are familiar? Which are surprising?

- • How does the artist’s choice of materials influence how you view the artwork?

- • How do the materials affect your interpretation of the artwork?

A. Balasubramaniam, Hold Nothing, 2012, Fiberglass, resin, and acrylic paint, 42 x 24 x 7 in., The Phillips Collection, The Dreier Fund for Acquisitions, 2014

A. Balasubramaniam, Hold Nothing, 2012

Hold Nothing is from Balasubramaniam’s four-part series entitled Kayaam (“invisible body” in the South Indian language Tamil). In this series, the artist created rubber casts of his own body, which he contorted and then recast in fiberglass. The results test what defines and confines human forms.

Jeanne Silverthorne, Dandelion Clock, 2012, Platinum silicone rubber, phosphorescent paint, and wire, 33 x 29 x 16 in., The Phillips Collection, The Hereward Lester Cooke Memorial Fund, 2014

Jeanne Silverthorne, Dandelion Clock, 2012

With forms cast in wobbly, silicone rubber, Silverthorne’s sculptures capture feelings of instability. After a clay model is made, Silverthorne creates a mold, pours in platinum silicone rubber, and then demolds her object. The phosphorescent pigments added to the rubber allow the work to glow in the dark, creating a haunting effect. Silverthorne’s overgrown creation invades.

“Dandelion Clock is a reminder of transience and mortality. It is infected by signs of morbid excess [its giant size], decay [the faded or ‘blown’ flower], and toxicity [its ability to glow in the dark].”—Jeanne Silverthorne

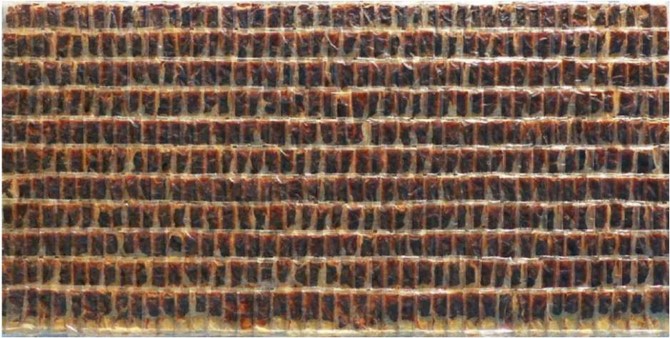

Dan Steinhilber, Untitled (Mustard Packets), 2003, Plastic mustard condiment bags mounted onto an acrylic panel, 24 1/2 x 48 in., Gift of the Robert S. Wennett and Mario Cader-French Foundation, 2021

Dan Steinhilber, Untitled (Mustard Packets), 2003

“Collecting and counting and sequence and repetition provide the idea and the embodiment of time.”—Dan Steinhilber

Steinhilber repurposes mass-produced consumer items manufactured to hold commodities that have been used or discarded. Here, he examines how time interacts with the physical and aesthetic properties of aged mustard packets collected from Mayflower Chinese Carryout in the Mt. Pleasant neighborhood. Acknowledging how his work has changed, Steinhilber explained: “This painting took 20 years to dry. This slow drying is part of the process.” His investigations suggest the possibilities held in mundane objects that often elicit memories.