This spring, former Phillips curator Beth Turner taught an undergraduate practicum at the University of Virginia focusing on Jacob Lawrence’s Struggle series. In this multi-part blog series, responses from Turner’s students in reference to individual works from the series will be posted each week.

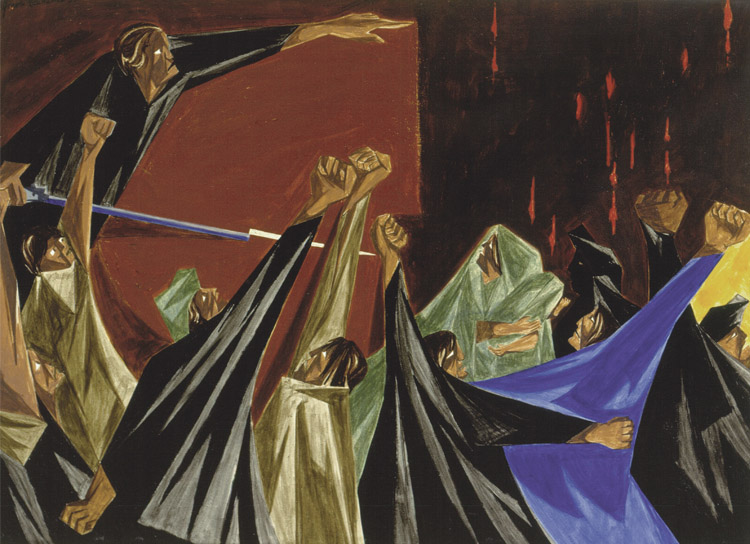

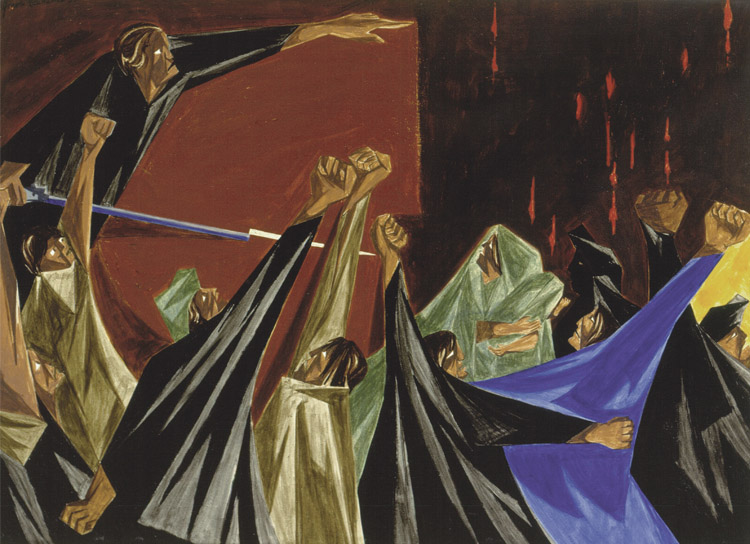

Jacob Lawrence, Struggle … From the History of the American People, no. 1: Is Life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?, 1955-56. Egg tempera on hardboard, 16 x 12 in. Private Collection of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross. © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“…is life so dear and peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?” – Patrick Henry, 1775

This panel shows the tenacious reaction to Patrick Henry’s 1775 call to arms. Given at the Virginia Convention in Richmond, VA, Henry’s words created such a fervor among the audience that George Mason stated, “Every word he says not only engages, but commands the attention and your actions are no longer your own when he addresses them.”

The forcefulness of a community coming together to fight a common injustice is something Lawrence saw as applicable not only in the 18th century, but also during his lifetime. The year of this panel’s production saw many uprisings in the fight for civil rights, including the December beginning of the Montgomery bus boycott. Tremendous tension was building as many southern states combatted the Supreme Court’s rulings for integration laws on multiple occasions, including the passage of Brown II, which stated that school integration must most forward “with all deliberate speed.” This unease spiraled in many communities and resulted in the murders of two Civil Rights activists, Reverend George W. Lee and Lamar Smith, as well as the murder of teenager Emmett Till for whistling at a white woman in Money, MS. Lawrence was no doubt aware of these tragedies and the massive amount of support they provoked. This panel is not only a call to arms for the Revolutionary War, but also aims to arouse the same fierce response to contemporary events. Using the upraised fists that would later become a symbol of the Black Panther party, Lawrence guides the viewer’s eye through the crowd before settling on the ominous upper right corner of the panel. Devoid of anything except for a few blood splatters, the future of the struggle is left in a state of ambiguity.

Madeline Bartel