In partnership with the US Department of State, The Phillips Collection collaborated with museums across Italy in fostering diversity and inclusion for audience and program development. Anne Taylor Brittingham, Deputy Director for Education and Responsive Learning Spaces, and Donna Jonte, Manager of Art + Wellness and Family Programs, discuss the virtual workshops created for the first part of this collaboration in February-June 2021.

The past two years forced us to think differently about the work we do. We had to shift how we work, how we think about programming, and how we develop partnerships and collaborations. Connections to new audiences and new ways of thinking about our work has come out of this difficult time.

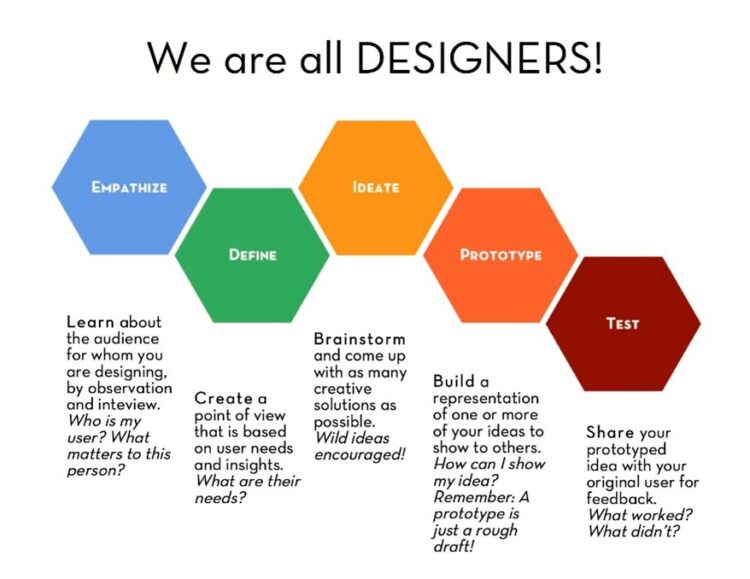

In 2021, The Phillips Collection conducted a series of virtual workshops with museums in Italy focused on bringing more intention to diversity and inclusion in audience and program development. Phillips education staff developed interactive virtual workshops to discuss the use of empathy to connect with and grow audiences as well as design thinking to encourage creative problem solving, innovation, and collaboration in programs and exhibition development.

Starting with “The Who”

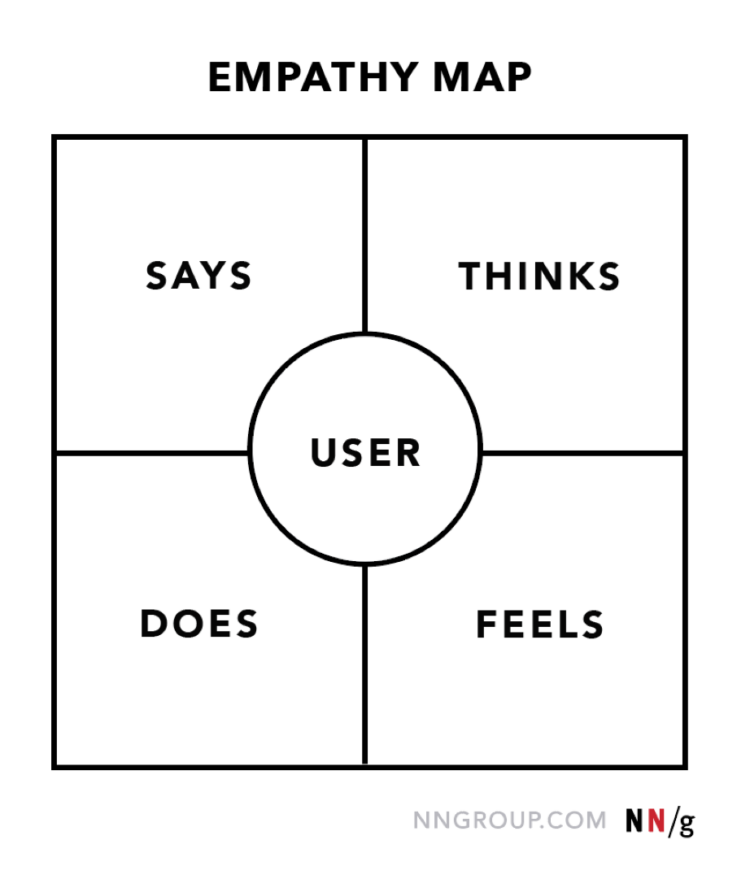

How can we use empathy to identify an audience we want to reach? It starts by thinking of our audiences as real people. For this exercise, we created a narrative about an audience we wanted to engage. We gave them a name and created a story. We personalized their experience and humanized them. And we got specific. How old are they? Where do they live? What do they do for a living? What do they do for fun? Have they visited the museum or participated in a museum program? If so, what did they think of it? What was their experience like? What impact did it have on them? We created an Empathy Map identifying what they would say, think, do, and feel about an experience with the museum.

We used design thinking to encourage creative problem solving, innovation, and collaboration in program and exhibition development.

Design Thinking: https://form3.com/thinking-about-design-thinking/

We continued our exploration of Design Thinking by asking each participant write a problem statement:

What is the problem you want to solve? (Be specific)

___________ needs to do ___________ because of __________

Then a staff member from an Italian museum was paired with a Phillips education team member to come up with 3-5 radical ways to meet the audience’s needs/solve the problem, thinking outside the box.

After four Zoom sessions, each museum implemented the ideas explored in the workshops at their individual museums. We got back together virtually in March 2022 to discuss the work we had been doing.

Stay tuned to learn more about the Phillips’s workshops in Italy.