Curatorial Intern Jason Rosenberg on Luca Buvoli’s Astrodoubt and the Quarantine Chronicles, which was recently acquired by The Phillips Collection.

“We’re all bored, we’re all so tired of everything…” Singer-songwriter Taylor Swift wrote these lyrics to New Romantics back in 2014! In retrospect, widespread feelings of burnout had been brewing for years; however, the recent surge in exhaustion and lethargy spurred by COVID-19 is a phenomenon unparalleled to any time before. Trapped in an endless cycle of flip-flopping restrictions and evolving viral mutations, life in the pandemic has felt like a catch-22 none of us will ever get out of. And yet, through it all, a beacon of hope has continued to shine on the other side: humor.

Philosophically, comedy has proven to be most valuable during these trying times. It offers a rare respite from the depressing reality we find ourselves in, constructing a shared spectacle to laugh at and rally behind. Fundamentally, it is a gateway to the unification of a community.

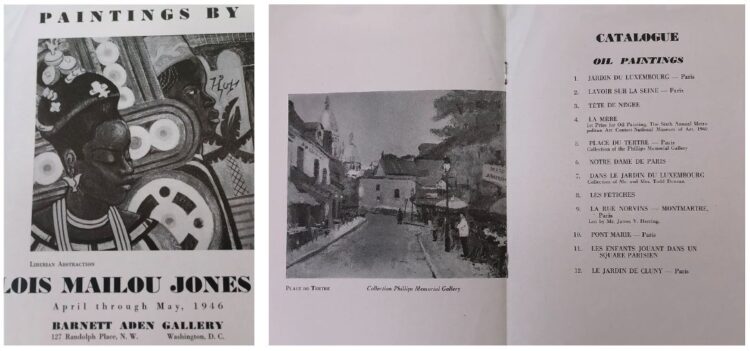

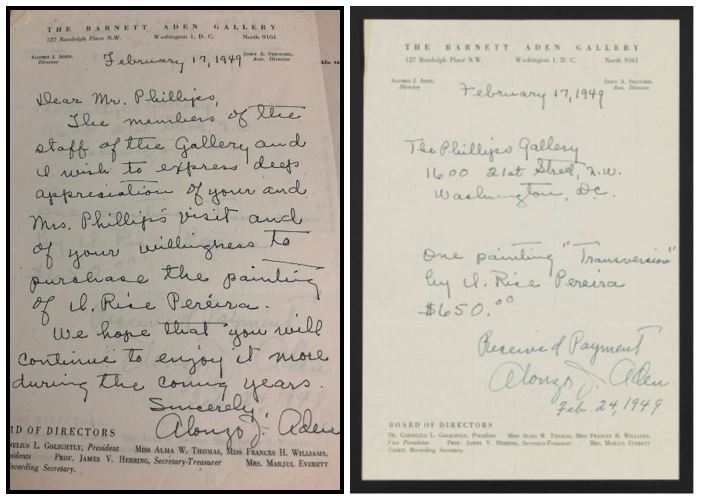

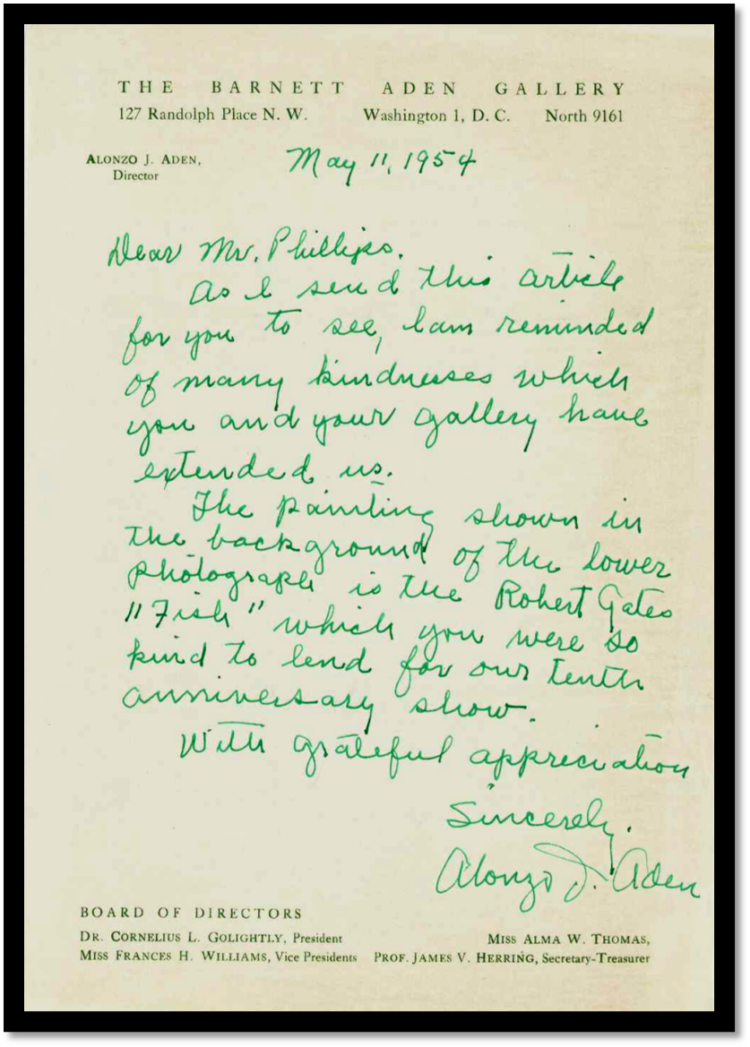

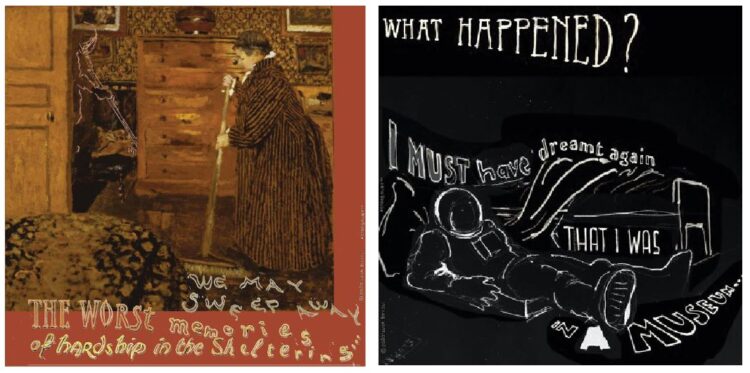

Back during the peak of reported COVID cases in summer 2020, multimedia artist Luca Buvoli tapped into this universal power through his Digital Intersections project, Picture-Present—part of his ongoing “Astrodoubt and The Quarantine Chronicles” series. Expanding on images from the Phillips’s permanent collection by a multitude of featured artists including Edouard Vuillard (Woman Sweeping) and Pierre Bonnard (Narrow Street in Paris), Buvoli integrated his satirical style through added texts and images to reflect on the emotional unrest experienced throughout the pandemic.

Select images from Picture: Present, an episode from Luca Buvoli’s Astrodoubt and The Quarantine Chronicles

His handwritten messages are witty and hopeful, often mirroring the subjects of the pictures they adorn; Vuillard’s woman with a broomstick, for instance, helps to sweep away the memories of hardship. Others, however, are intentionally ambiguous and open-ended, such as the last scene in which the main protagonist Astrodoubt finds himself awakened, wondering if the coronavirus is still around or whether it was all a dream.

As a whole, Buvoli’s digital 12-panel storyboard reads as a narrative of isolation, anxiety, and wishful delusion; feelings we’ve all collectively experienced within the span of the past few years. As the first commissioned Digital Intersections showcase, Picture: Present welcomed audiences to the same virtual world as Astrodoubt: a remote landscape where the museum’s past could be explored and take on a new life remotely.

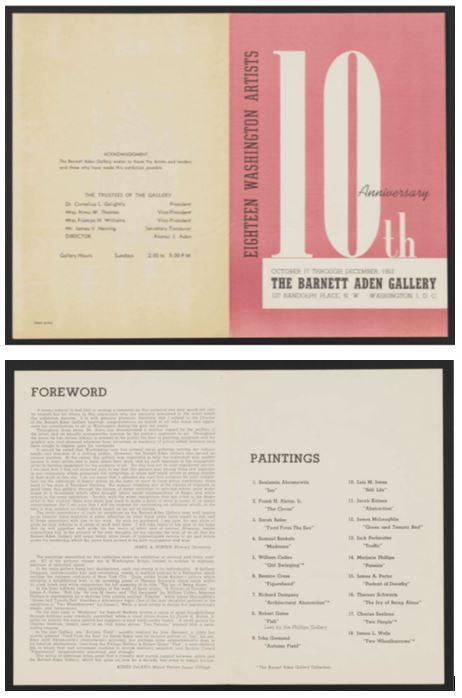

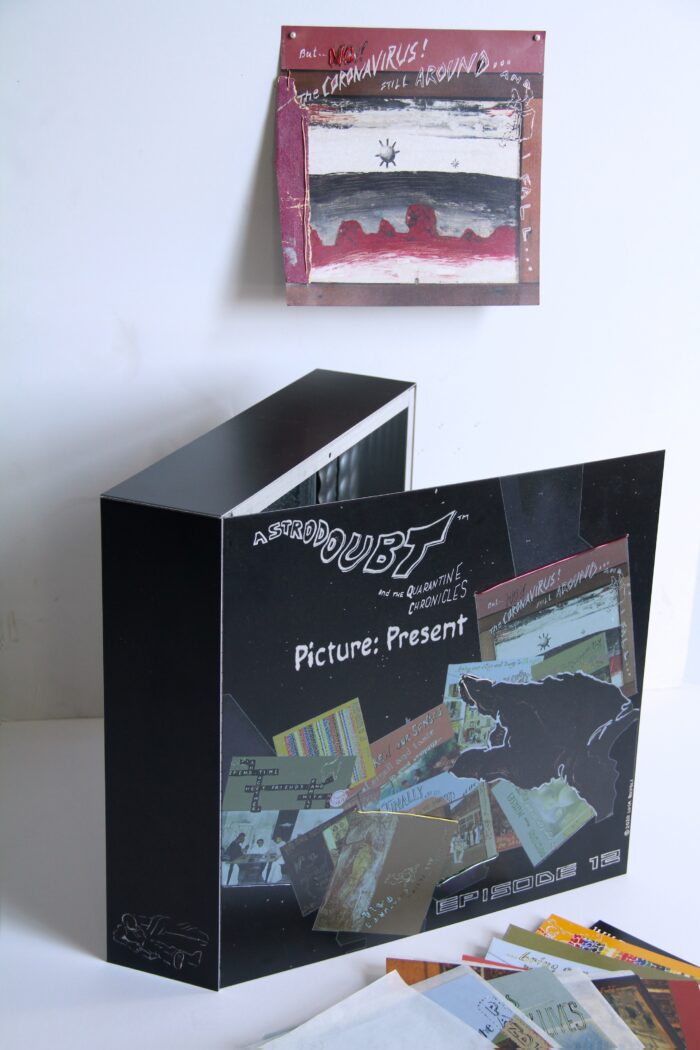

Today, Buvoli’s project marks a unique time in our cultural history, connecting the past with the present by means of an intangible digital medium ubiquitous to everyday life. Recently on view at the Cristin Tierney Gallery in New York City, Astrodoubt’s journey has been inverse to many others in the art world: evolving from digital back to analogue. The Phillips’s recent acquisition of Buvoli’s physical Cosmos-In-The-Box book edition of “Astrodoubt and the Quarantine Chronicles” logs the first of many interdisciplinary, dynamic exhibitions. Picture: Present paves the way for a new era of accessibility in art, a facet central to the long-term survival of museums and artistic institutions in the years to come.

Luca Buvoli, Astrodoubt and the Quarantine Chronicles (Episode 12), 2021, 13 collaged drawings in metal box each: 7 x 7 in; The Phillips Collection, The Dreier Fund for Acquisitions, 2021