At Karen Schneider’s retirement party last week, she shared with the staff some of her favorite moments over her 41 years at the Phillips (which included a lot of parties!). We’re excited to share some of them with you here.

Becoming the Phillips Librarian: Laughlin Phillips, son of Duncan and Marjorie Phillips, was the director when I started at the Phillips. He was a kind, gentle man who was also shy and modest. He loved getting to know the eccentric staff and delighted in seeing our artwork. He was also a terrific writer and editor and he would make whatever we wrote infinitely better. My background is in studio art. I was an artist in residence for two years and taught art to middle and high school students at National Cathedral School. I needed something for the summer and came to the Phillips. During my interview, I was asked if I had worked in a library before. I said yes, at Bennington College. Laughlin (he liked to be called Loc) led me upstairs to the the library, which was on the fourth floor of the house. The room had been Marjorie Phillips’s studio and the site of the Phillips Gallery Art School as well as Loc’s nursery. Loc opened the door and it was complete chaos. There were workmen on ladders building bookshelves, drop cloths spattered with paint, and the radio was blaring. Loc looked down at me and cleared his throat, which I later learned was a sign that he was nervous. Just then two cats raced across the room, Bazooka and Fiona. Loc asked me, “Do you think you could do something with this?” I said, “Yes.” I worked at the Phillips that summer and really enjoyed it. There was much to be done. I wrote a list of why the Phillips needed a librarian and what that person would do and I nominated myself. When I was back at National Cathedral School the head of the art department came up to me with a wide-eyed look and told me that Laughlin Phillips was on the phone. He told me “We like what you wrote. You’re on!” The fact that I had no art history or library degree did not matter to him. He was a good judge of character and loved to hire artists. He delighted in all of our eccentricities.

The Ham: John Gernand, the museum’s first registrar, fed Bazooka and Fiona promptly at 1:00. The cats came into his office precisely at 1:00 and John unwrapped aluminum foil which contained thin pieces of ham. After they had their lunch, Bazooka relaxed belly up on John’s desk under his lamp which was next to his phone. I always wondered what would happen if he received a call from the MoMA. Did the person on the end of the line hear Bazooka go Rarr?

Art Barn: One year we had our staff show at the Art Barn in Rock Creek Park. One of the staff members came running up to me—”Laughlin Phillips bought your work on paper!” I thought, “Drat! I should have added more zeroes to the price!” Loc wanted to talk to me about my work, which he put on the mantle of his fireplace next to a Braque still life.

The Hat Party: We had a hat party in the original courtyard. Everyone had to wear a hat. There was a fringed lampshade hat that someone found in one of the offices, a Sherlock Holmes hat worn by Jim McLaughlin, our curator, a red fez as well as my black pillbox hat. By the end of the alcohol fueled event, Giacometti’s Monumental Head in the middle of the courtyard had a huge pile of hats on top of its head.

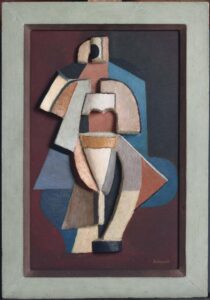

Come as a painting party: One of our best parties was one in which we dressed up as a painting. I think that Bill Koberg made a hat that had a reproduction of Walt Kuhn’s Plumes. I was the guitarist in Manet’s Spanish Ballet and made my guitar using foamcore.

Present at the Unveiling: In the 1980s, the small staff was permitted to watch the uncrating of works of art, something that would be forbidden today, when only the curators, registrars, preparators, and director are allowed that privilege. I will never forget the joy experienced by all of us as a stunning Bonnard landscape from a French museum was unpacked from its enormous crate. It was included in a major Bonnard exhibition in 1984.