Alma Thomas taught art at Shaw Junior High School for 35 years. She said: “People always want to cite me for my color paintings, but I would much rather be remembered for helping to lay the foundation of children’s lives.” To honor and connect to Thomas’s career as a teacher, we asked DC-area educators to respond to works of art in Alma W. Thomas: Everything Is Beautiful . These educators participated in the Phillips’s 2021 Summer Teacher Institute, exploring ways to adapt arts-integrated lessons to their students. Read their perspectives on how they personally connected to Thomas’s artworks.

Read more responses in Part II

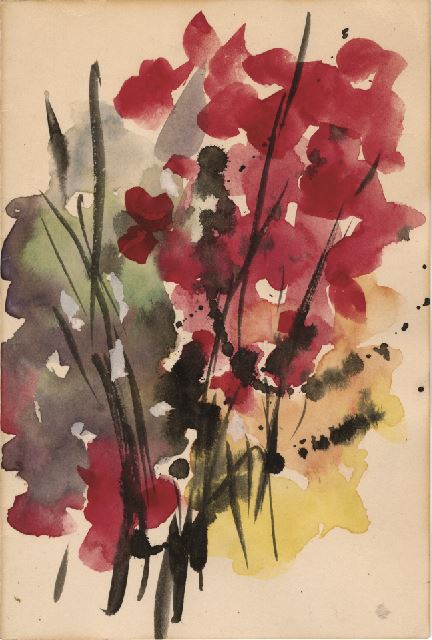

Alma W. Thomas, Cover of a birthday card, early 1960s, Watercolor on paper, Closed: 7 × 5 in., The Columbus Museum, Gift of Miss John Maurice Thomas in memory of her parents, John H. and Amelia W. Cantey Thomas and her sister Alma Woodsey Thomas, G.1994.20.141

How do you select a greeting card—by image outside or by message inside? If you are like me, I am drawn to the image first. The image strikes my eye with a message of its own.

This small watercolor illusion of a bouquet of flowers has been carefully arranged by Thomas, as if the flowers are laid out, waiting to be placed in a vase. Notice how she carefully layers her bleeding colors starting with a background of blotches of yellow, then greenish grey, and topped by red. Black streaks give structure to the blotches making the flower illusion hold.

What kind of card would you select this painting for? Birthday? Mother’s Day? Sympathy? What do you think is the written message inside? Who did Alma Thomas have in mind when she painted it? What message is she sending you?

—Mary Beth Bauernschub, School Librarian, Beltsville PK-8 Academy

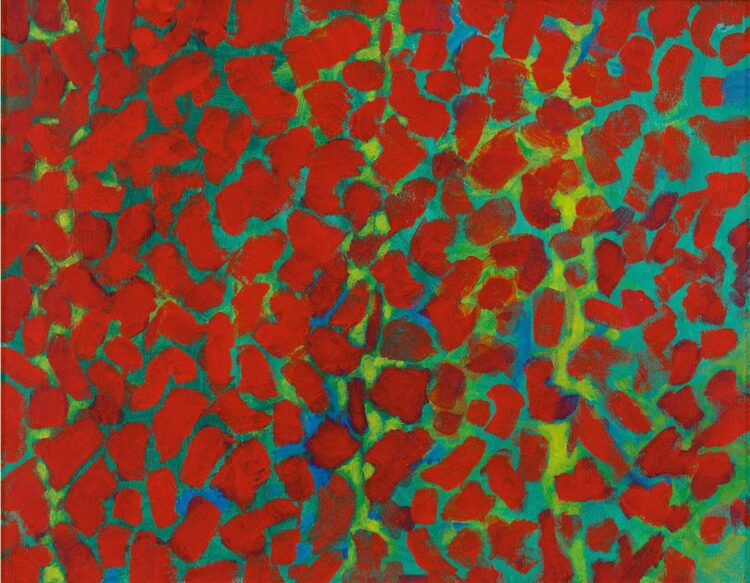

Alma W. Thomas, Falling Leaves, Love Wind Orchestra, 1977, Acrylic on canvas, 21 1/2 x 27 1/2 in., Private collection

When leaves seem unembarrassed and stubbornly brave to show their ruby color on bright bold days, I know that nature calls us in a whisper to say, “Don’t fear your evolution. Everything must change.” So I dance with abandon as the gentle wind blows. I will not fear change. I will let it all flow. I will trust in the process, this journey, this life. I will trust in the cycles, the beauty of life.

—Colie Aziza, Early Childhood Special Educator, Pre-K, Frances Early Childhood Center

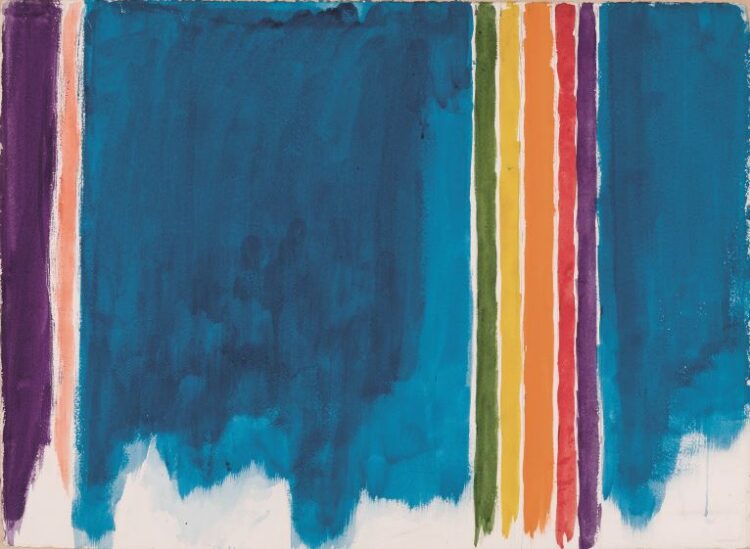

Alma W. Thomas, Sea of Tranquility, c. 1971, Watercolor on paper, 22 x 30 in., Alex and Lissette Stancioff

Gazing at this beautiful masterpiece of Alma Thomas reminds me of my own journey migrating from the Pearl of the Orient Seas to the Land of the Free. The challenges of migration offer opportunities for growth and resilience. Migrants have varying circumstances and make a move for different reasons, including economic, socio-political, and environmental factors. Initially, for me, it was the call to liberate myself from the hostile working environment back home, an experience that adversely affected my mental health and well-being.

Walking in the Manila Bay area in the Philippines on a sunny day, I had an epiphany. It was time to embrace change and pick up the broken pieces of my inner self. Luckily, I was offered employment in the United States, and after a few years of service, I was nominated for a countywide recognition. It’s also in this country where I found my lifetime partner, and we have been blessed with a miracle baby girl. Nowadays, I am making the time to explore what truly makes me better, greater, and happier. I knew if I did not take the risk, I would never have reached my own “Sea of Tranquility.” Are you ready to find and explore yours?

—Irene De Leon, Service Coordinator / Early Childhood Special Educator, Judy P. Hoyer Early Childhood Center