Over the past year, The Phillips Collection has distributed over 2,000 Wellness Kits to families near our campus at THEARC (1801 Mississippi Ave SE). These kits contain masks, hand sanitizer, toys, and all the art supplies you need to complete an included activity. Now we want to do the same activities with you! You can assemble your own Wellness Kit activity by purchasing the supplies and following the instructions below.

For this project, you will need:

- Cardstock paper (8.5 x 11 in.)

- Markers

- Model Magic

- Book folding template (from the National Museum of Women in the Arts)

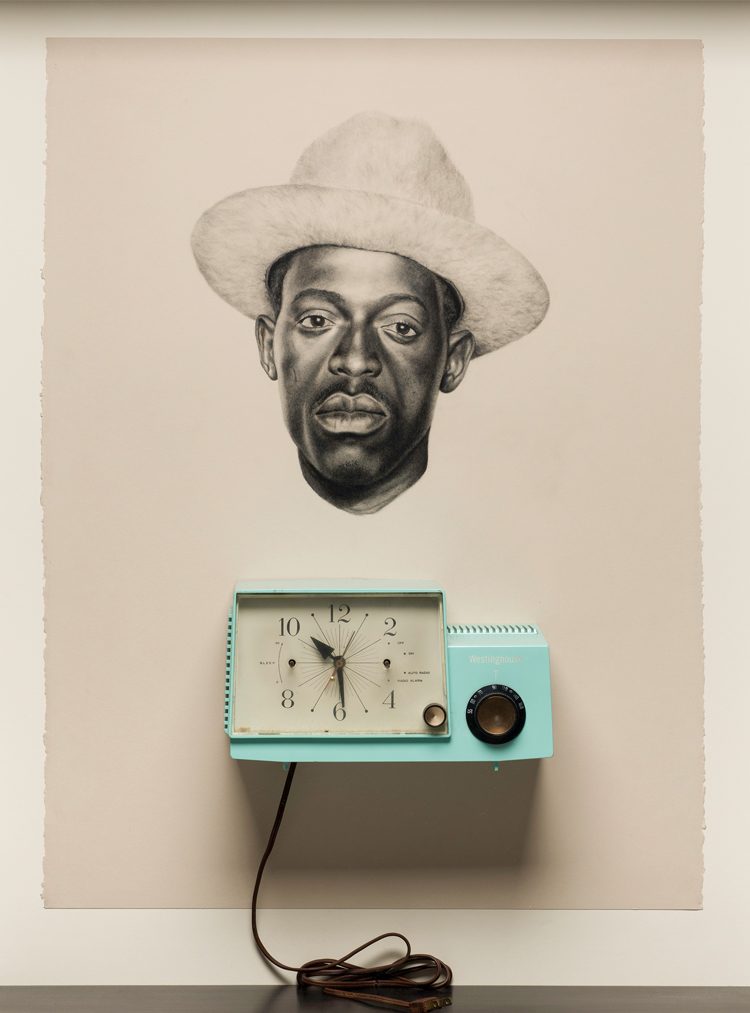

Whitfield Lovell, Kin XXXV (Glory in the Flower), 2011, Conté on paper, vintage clock radio, 30 x 22 3/4 x 5 3/4 in., The Phillips Collection, The Dreier Fund for Acquisitions, 2013

Look Closely:

“The importance of home, family, ancestry feeds my work entirely. African Americans were generally not aware of who their ancestors were, since slaves were sold from plantation to plantation and families were split up. Any time I pick up one of these old vintage photographs, I have the feeling that this could be one of my ancestors.”—Whitfield Lovell

Look closely at the man in this work of art. Who do you think he is? What might he be thinking? How could he be feeling? Whitfield Lovell drew this face by hand. He studies old photographs and carefully draws every detail. Notice the clock radio below the drawing. How might the clock be connected to the portrait?

Inspired by old, anonymous photos, Whitfield Lovell created the Kin series. Kin means a family member or relative. Even though Lovell does not know the people he draws, he imagines a kinship with them. This kinship makes him want to spend time with them, creating detailed portraits. He envisions their full life, choosing objects that represent their complex identity. By celebrating these people in art, he makes them important and makes sure they will no longer be forgotten.

Celebrating Kin:

Inspired by Whitfield Lovell, we will create art that celebrates people who are important to us. Lovell uses three-dimensional frames, or “shadow boxes,” to display his drawings and found objects together as one work of art. In this activity, we will be creating a three-dimensional object and a house-like structure that will serve as a frame for our object. We can decorate our paper “frame” with drawings that celebrate our special person.

Sculpt Your Object:

- Before you begin, decide who you will represent in your art. Why is this person important to you?

- Next, think of an object that relates to this person. What does this object tell us about this person? Does the object connect to a memory you have of this person?

- Sculpt your object using Model Magic.

- You can add color to your sculpture using markers.

- Model Magic hardens when you leave it out to dry. If you want to create your sculpture during the Sunday workshop, do not open your Model Magic ahead of time.

Fold Your Paper “Frame”:

- Find your cardstock paper.

- Follow the diagram from the National Museum of Women in the Arts to create the “frame” for your sculpture.

- Stand your frame up so that it looks like a house.

Create Your Portrait:

- Decide where to create your portrait on the frame. Think about how you will display the frame with the sculpture.

- The portrait can be as realistic or abstract as you want. Whitfield Lovell’s portrait is realistic; it looks like a photograph. An abstract portrait uses symbols and colors to represent how a person makes you feel.

- Use markers or any other art supplies you have.

- Get creative! You can decorate any and all sides of the frame.

- Display your frame and sculpture together.

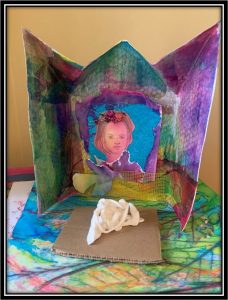

Portrait of Frida Kahlo with birds and roses.

Portrait of artist’s mother with abstract sculpture inspired by nature walks.