The Phillips Collection is proud to partner with @samesexinthecity to celebrate, honor, and examine queer art during Pride and beyond. Here, @samesexinthecity discusses what is at stake by queering art history, exploring a history of LGBTQ identity through art history, and pairing artists with this facet of their identity. Visit us on Instagram @phillipscollection to learn about some queer artists in our collection.

Why should a museum like The Phillips Collection focus attention to queer art and artists?

What is at stake by queering art history, by exploring a history of LGBTQ identity through art history, and by pairing artists with this facet of their identity?

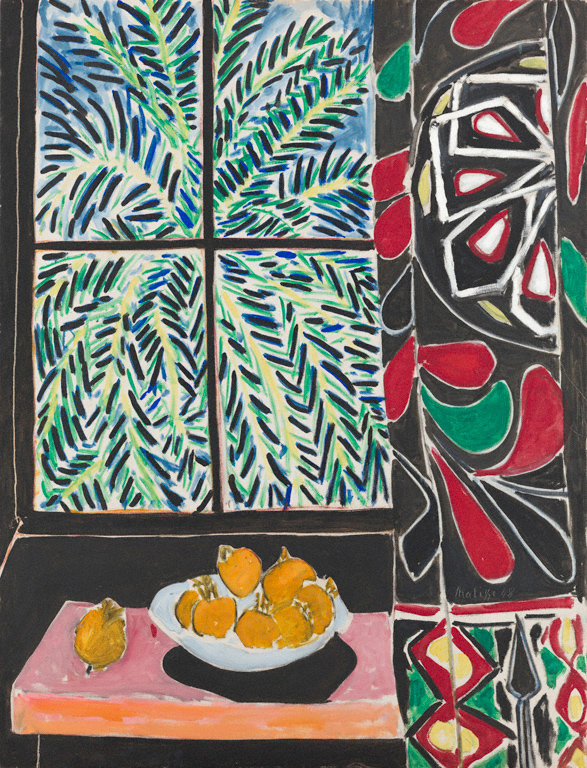

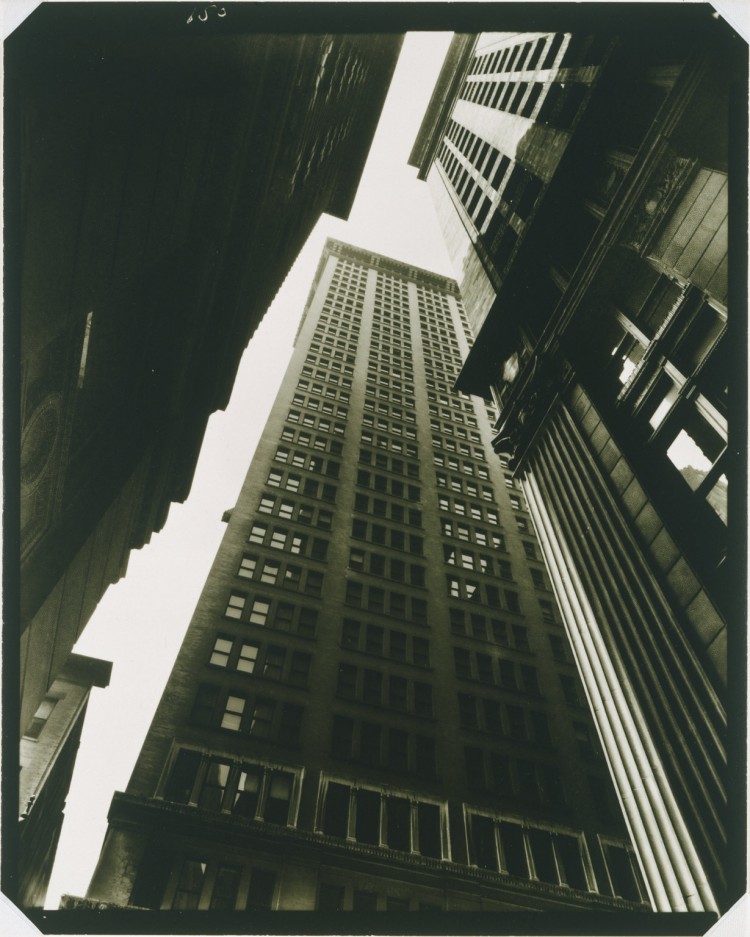

The works within the Phillips’s permanent collection don’t necessarily shout “gay” to a viewer. Artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe, David Hockney, and Charles Demuth, who gained notoriety even in their lifetimes for the frank, sensual depictions of same-sex desire are represented in the the Phillips’s collection; however, their artworks in the collection don’t address any of those themes. Other artists, such as Zilia Sánchez, Howard Hodgkin, and Whitfield Lovell, create artworks that at first can appear abstracted, solemn, and to be exploring other ideas, but they also do not exactly scream “queer.” Some artists made the decision within their lifetimes to disavow categorization by this aspect of their identity, choosing instead to push different narratives about their art-making and place in the art world. Many artists, especially in the early 20th century, preferred to have their works judged just as artworks, and rejected categorizations based on race, gender, and sexual identity (Berenice Abbott’s letter to artist Kaucylia Brooks comes to mind.). However, the impact of the art object on us as a viewer can only be enriched by acknowledging that identity plays a part in the artworks’ creation and our reading of it.

I’m always struck, when considering these types of questions, and reminded of a 1999 artwork by Harmony Hammond, titled Small Erasure #3 (not in the Phillips’s collection). Hammond spent several years compiling lesbian artists and artworks for her 2000 publication Lesbian Art in America, the culmination of decades of work attempting to fit queer women into the New York art world conversation. In the book’s introduction, Hammond references media attempts to “commodify and consume the lesbian [and her art] as chic spectacle”—the book is literally Hammond’s way to resist such consumption. Small Erasure #3 consists of a letter, one of many that Hammond received from artists who did not want their artwork in her book for fear of reprisal and art world shaming. Hammond obscured the letter’s text with eggy latex and paint, creating yellowed streaks and areas of shadow, referencing the self-erasure that queer artists were continually fighting against at the same time as art world erasure and homophobia. The piece also speaks to self-censorship that artists underwent, and to some extent might still undergo today.

Nikki S. Lee, The Lesbian Project (14), Chromogenic print, 28 ¼ x 21 ¼ in., The Phillips Collection, Gift of heather and Tony Podesta Collection, Washington, DC 2011

The history of art has long upheld the myths of individual genius, separated from sexuality as it best suits the historian. However, at the same time, the cultures, codes, and images of homosexuality has long been a resource for artists of all identities to push the boundaries of creating. Take the art object in the permanent collection that has the most overt depiction of same-sex desire: Nikki S Lee’s The Lesbian Project (14), created by an artist who does not claim a queer identity, but instead created the photograph as part of an ongoing exploration of cultural signifiers of various groups. Her art has received widespread acclaim for challenging the very question about the importance of identity, and assimilation. Seeing The Lesbian Project (14) in a gallery at the Phillips was probably the first time I had seen a contemporary artwork of two women kissing—and despite complicated feelings about the project and artist, I do feel it’s important to have images of same-sex desire in museum collections.

The definitions of queer, gay, lesbian, homosexual, identity, have all changed and remain unfixed as we grapple with new understandings of identity. And as Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer state in their tome Art and Queer Culture, inserting queer culture into the history of art forces an expansion of the boundaries of what art and history actually is. A museum’s identity is not fixed, but changes institutionally as the individuals within it evolve and uphold different ideas—why shouldn’t the art and the art history upheld by a museum change too?