Artist Shelley Lowenstein of the Otis Street Arts Project reflects on the workshop she led: WIRED: Line Drawing in Space.

What a year! How can I bring joy into a world turned upside down?

That was my first thought when our studio (Otis Street Arts Project) was asked to create a series of hands-on zoom art classes for The Phillips Collection. I reluctantly volunteered even though I don’t enjoy public speaking. Why not? I asked my inner voices. If not now during a pandemic, then when? Growth. Face your fears and do it anyway.

For some time, I had been weaving with wire, and I decided to share my endless enthusiasm for Alexander Calder while creating Calder-inspired wire portraits with the Zoom participants. It was easy to be enthusiastic about this artist. I fell in love with Calder as a child. I was so amused by his toy figures and hanging portraits. I was not alone: “My fan mail is enormous; everyone is under six,” explained Calder. He believed that “above all, art should be fun.” And what better way to create a relaxed, inclusive few Zoom hours than by focusing on the joyful Calder and his brilliant work. And so, we began to work with the wire while learning more about the man.

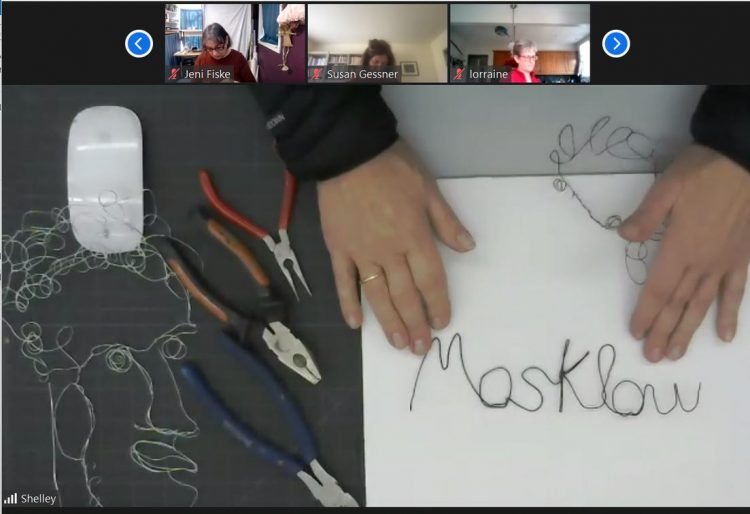

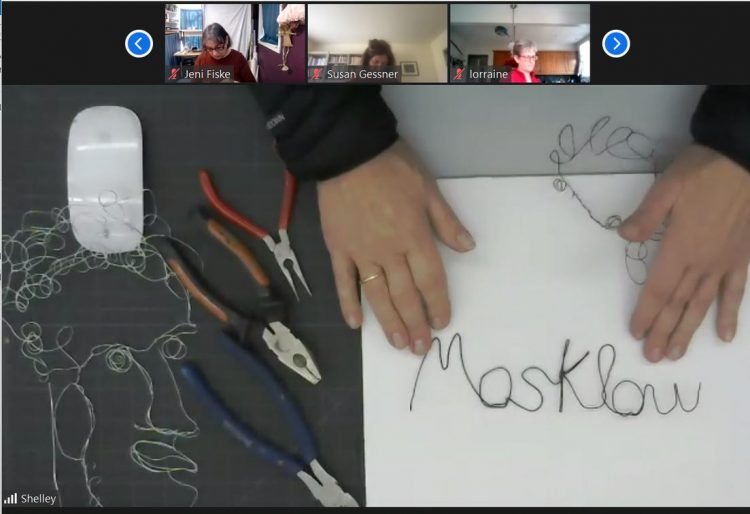

Drawing with wire during the online workshop

Alexander Calder, known as Sandy, was a playful genius. He became one of the most beloved American sculptors of the 20th century. Only recently, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City opened a new exhibit about him. From the review in the New York Times: “The Modern has welcomed Calder back with a beauty of a show that, over the next several months, will make the world a better place.” Calder once said, “I think best in wire.” He was a big man with large strong hands, perfect for bending wire. And he loved to laugh, seeing humor in the world.

After college, he went to Paris to become an artist. He rode a bright orange bicycle around town, with a large spool of wire over his shoulder. He’d studio hop, visiting his famous artist friends to see what they were doing. And often, he would create a portrait likeness of these celebrities, sometimes on the spot, by bending wire—Joan Miró, Josephine Baker, Fernand Léger, Edgard Varèse, and many more. He called himself an “illumination engineer” because the shadow cast by the wire was as important as the portrait itself. Simply put, he was contour drawing in space.

It was on a visit to the studio of Piet Mondrian that his world changed. Studying Mondrian’s geometric paintings of red, blue, and yellow shapes, Calder’s mind turned to the idea of “kinetic art.” What if those big shapes of color could actually move? What if I can draw in space? And that “spark” evolved into the invention of the mobile.

Drawing with wire during the online workshop

Via Zoom, the participants and I began to bend, twist, and curl wire. We made circles and squares. We made hearts and zig zags. We learned different ways to join wire. I recommended using 18-20 gauge wire because it’s easier to bend than what Calder actually used. Basic tools included flat-head pliers, needle-nose pliers, and wire cutters.

In no time, some 54 participants were getting comfortable with the materials. We examined a number of Calder portraits, how he elegantly joined wire connections, how he created various shapes, and how he created simple contour drawings―just the simple outline of the features of a face. No shading. No color. No value. Calder’s genius―he emphasized only the prominent features, not the detail, because our mind can fill in the blanks.

And soon, to the amazement of the Zoom participants, we were making three-dimensional portraits. There was joy in the air on that Zoom. Participants were chatty, asking questions, sharing their work, laughing. We were “playing” with art, as Calder had advised. And the feedback was heartwarming. Above all, art should be fun.