Cicely Ogunshakin, a 7-8th grade Social Studies teacher at School Without Walls at Francis-Stevens, reflects on her experience in the Phillips-UMD Prism.K12 course. The student artwork produced from the course is shared in the Community Exhibition The Virtual Classroom as Artspace.

When I signed up for this course, I really didn’t expect it to be so good. My past professional developments had been kind of dry with few takeaways that I could implement in my class, but I was excited to learn about different ways I could integrate art into my classroom. There were some other benefits as well—professional learning units (PLUs), a year membership to Phillips, the ability to network with other educators, and the class would be 100% virtual. These all made it easier to hit the register button.

I admit that when I received my art supplies in the mail, I was immediately giddy. Crayons, markers, construction paper, colored pencils, a couple of sharpies, glue sticks and some other art materials made me feel like a kid again.

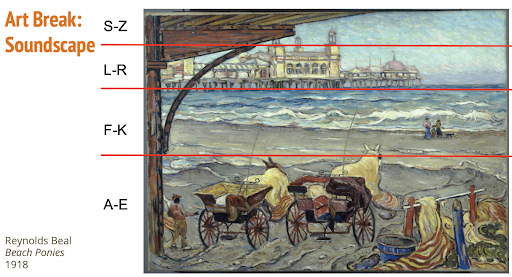

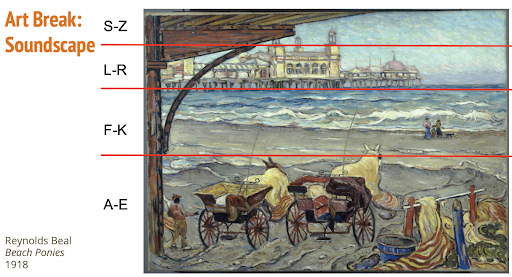

On the first day, we were thrown into an ice-breaker activity in an attempt to set the pace and tone of the course. It was a strategy called Soundscape in which we had to examine different parts of a painting and make sounds related to the painting. In this picture there were horses, carriages, a pier, an ocean, and a family with a dog. Sounds of Nahhhhhaaa, swooshhhhh, clop clop clop, stomp stomp stomp, ruff ruff, and so on, filled our virtual space. We were grown adults on a Zoom call making these sounds, actually practicing this strategy to be able to bring it alive in our very own classrooms.

Screenshot from Week 1 course presentation.

The foundation of our class was based on the Prism.K12 strategies of Identify, Connect, Express, Empathize, and Synthesize. As we progressed over the weeks, I was intrigued to experience how each lesson was relatable and applicable to all of the teachers. Our Facilitator, Hilary, made it look simple. Each week, I left the virtual class excited and feverishly searching The Phillips Collection to see what I could use to implement this strategy in my own classroom.

Part of the class required that you complete a Core Project. I decided to focus on an upcoming unit, The American Revolution. The goal was for students to use the 7-Word Story Strategy to express their ideas, thoughts, and emotions through art and words. I gathered some historic protest images from the Internet and had students examine one of those images.

As they examined the images, they answered these questions:

- -What do you see?

- -What do you hear?

- -What do you feel?

- -What do you think?

- -What do you wonder?

I also had them think about the photographer’s perspective and whether a person could tell a compelling story based upon the image(s).

Here are are some of the 7-word stories that my students created:

- -Screaming, running, woman distressed, wrong unjust death

- -Preferences respect me, respect you respect LGBTQ

- -Humans, the Earth’s protection and inevitable destruction

- -Let me be who I want. Free.

- -Dreamers and believers are dying in sorrow

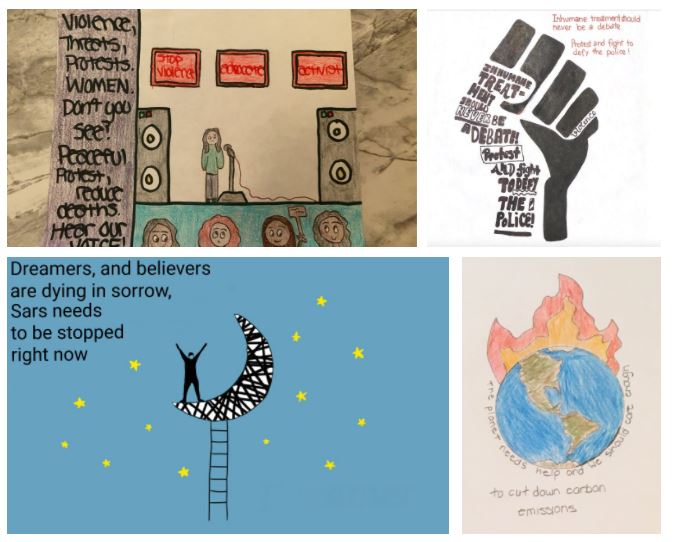

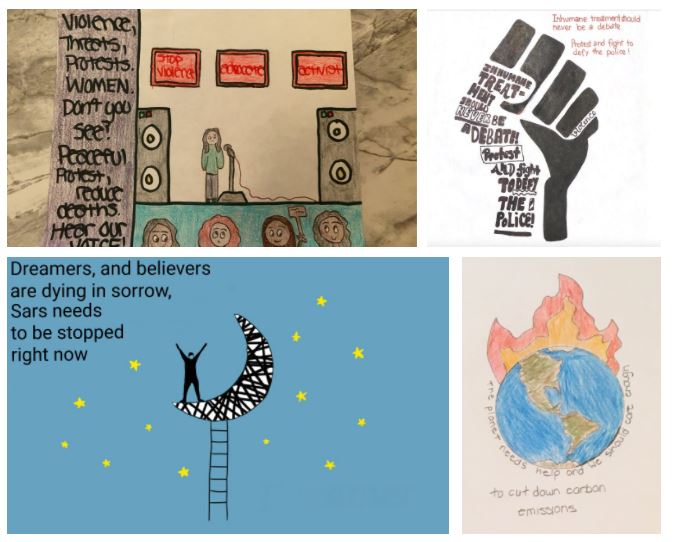

For the exit ticket students had to add 7 more words that presented a possible solution for the same image. They also had to include a visual. Students had the option of completing this activity on paper or digitally.

Examples of student artworks with their 7-word stories, 7-word solutions, and a visual.

My students enjoyed this lesson. They analyzed and shared ideas through collaboration. They learned about other protest movements through images, reflecting on the artist’s work and purpose. They used key words to describe an image and they added 7 more words to identify a solution, all while expressing themselves through their artwork. My students were excited to share their creations and receive compliments from their peers. Using this activity changed the whole mood in my class, which was great since we were in virtual mode and have been virtual since last year. So if you are wondering whether or not to click register, just CLICK IT! You will not be disappointed.