The Phillips Collection invites everyone to participate in Community in Focus, a community project to capture a unique photographic snapshot of an unprecedented year. We asked you to show us your inimitable spirit, suffering, joy, and resilience, and here are some images that captures those human emotions that connect us all. Stay tuned for more photos and submit your own!

Kristian Ivanov, April 6: The photograph was taken during the first wave of the lockdown in New York in early April. I was coming back home after more than 24 hours of flying internationally, the last shoulder of which was a commercial flight from London to New York with only three passengers on board including me. Upon landing, I couldn’t go straight back to my house so I quarantined at a friend’s empty apartment in Clinton Hill for 3 weeks. The first time I heard everyone’s claps and shouts expressing their gratitude to all front line workers I grabbed my camera and captured a couple of neighbors standing on their balconies cheering. It was a truly moving moment to experience the multitude of people’s reactions to what was happening in New York and around the world.

Nikki Brooks, May 30: While participating in a Black Lives Matter car parade, I happened to pan over to the left of me to see this black joy! I saw the generations, and the future all in one.

Catiana Garcia-Kilroy, July 10: “Justice can’t wait” The photograph was taken on H street in DC, diagonally from Lafayette Sq.

Sara Allen, July 20: This is the solitude experienced during the summer of 2020 when I could not get together with my family (which lives in CA and Israel) for our annual reunion at the Lebanon Opera Festival in NH. I am a widow and live alone. This is meant to express the absence of loved ones, the loneliness, the solitariness of the experience of COVID.

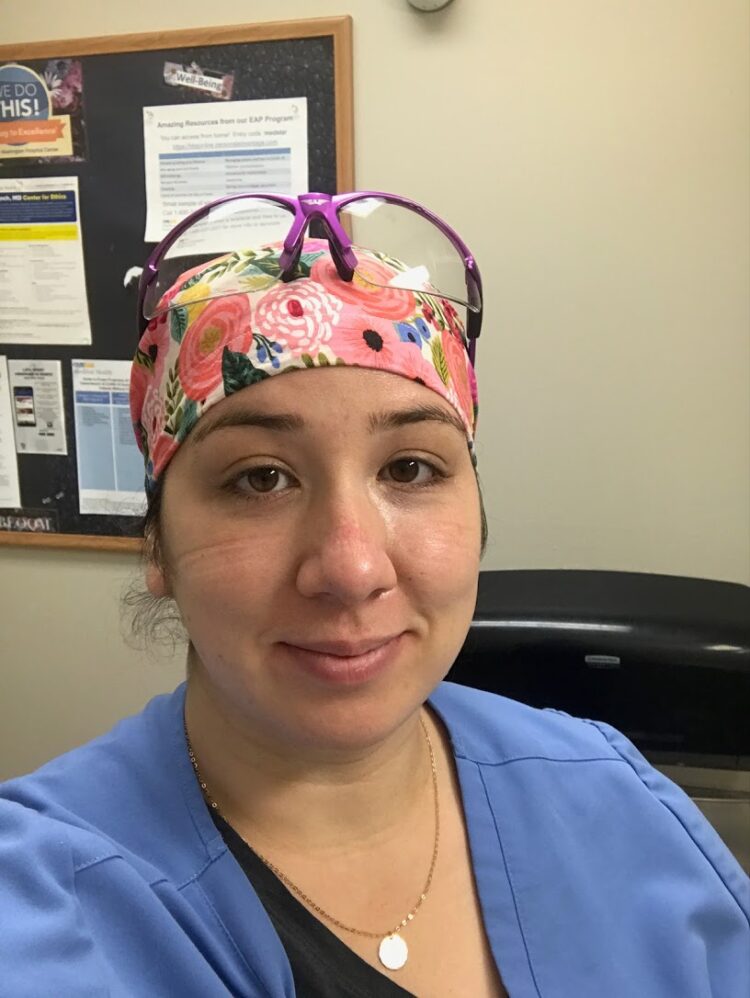

Carly Kinney, August 29: This was a selfie my wife Carly took during her work on a Neuro Trauma ICU in Washington DC. The combination of the N95 pressure marks, her exhausted eyes, and determined smile paint a vivid picture of nurses fighting on the front lines of this crisis.

Geoff Livingston, Nov 7: This celebrant and her nursing child proudly claimed victory over Donald Trump. I am not a political pundit, but I am the father of a 10-year old young lady. The historical arc of the United States forever changed when Kamala Harris became the country’s first female Vice President-Elect.

Michael Aaron, September 16: The lions at the National Zoo entrance let visitors know that you need to wear a mask to enter.

Jenny Mendes, November 2: I made these vignettes daily for the month before the election as my personal vote campaign. Made from nature where I live, a daily meditation with a positive intention. Once I began posting them on social media I realized it was not only for me but that they brought hope, joy and positive energy to many people. This is a compilation of some of them that I shared on election day. Every vote really did matter this year more than ever.