Curatorial Associate Wendy Grossman reflects on the process of presenting the exhibition Man Ray, African Art, and the Modernist Lens—and the potential controversies surrounding it—at the Phillips in 2009.

The flurry of conversations and controversies in the museum world in the wake of our society’s efforts to reconcile a history of racial inequity in both institutional structure and programming has prompted recollections of my experience a decade ago in bringing to fruition the exhibition Man Ray, African Art, and the Modernist Lens at The Phillips Collection. Looking back to look forward is important for our institutional identity. I believe that hosting this exhibition is something for which the institution can and should take pride.

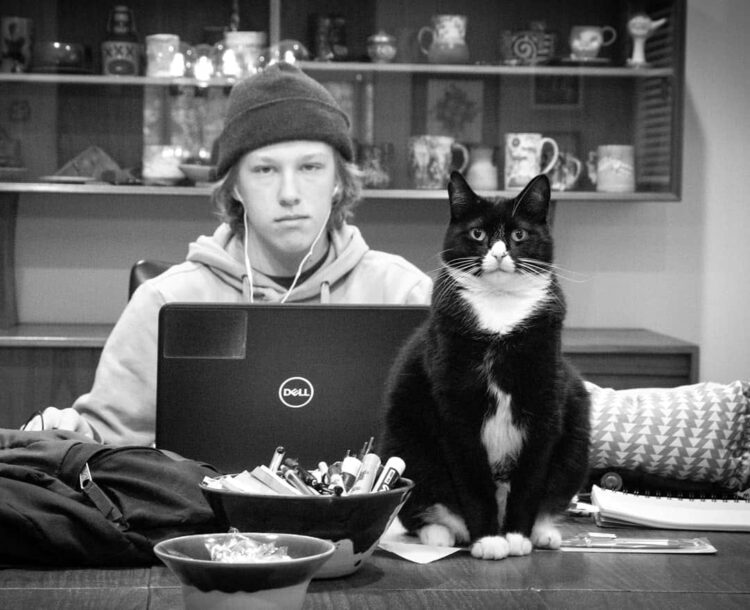

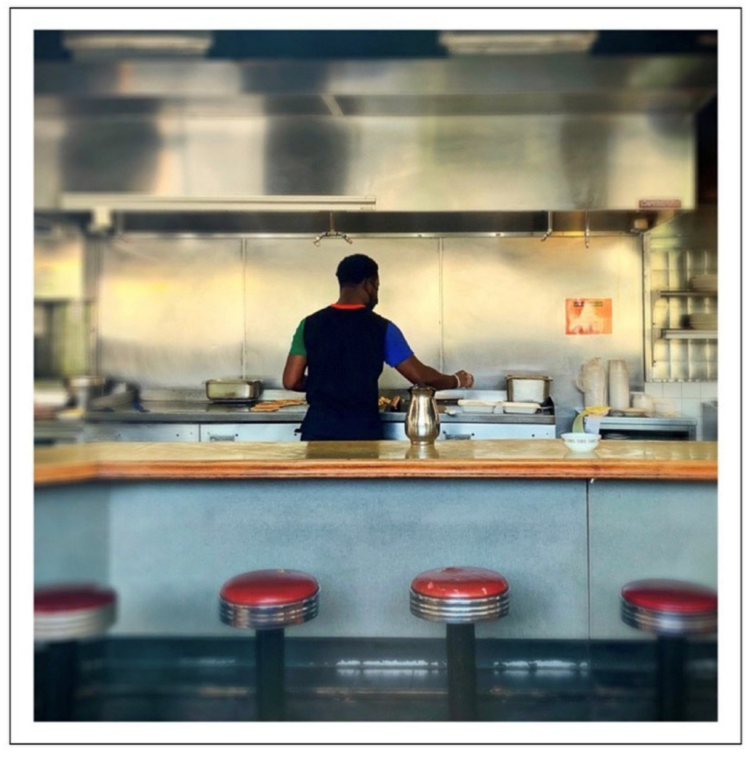

Installation photographs of Man Ray, African Art, and the Modernist Lens at The Phillips Collection. RIGHT: Kuba drinking vessel (Democratic Republic of the Congo) and Portrait of James Lesesne Wells by James Latimer Allen. Both on loan from Howard University, Washington DC

The product of years of research investigating the role African art and culture played in the construction of modernism and recognition of photography’s central place in this process, Man Ray, African Art, and the Modernist Lens took on thorny issues of race and representation within this framework. Although the Paris-based American artist Man Ray was the marque name and fulcrum around which the interdisciplinary project was constructed, the exhibition also featured far lesser known modernist photographs alongside the exact African sculptures that inspired them. Significantly, it brought to light a previously unrecognized relationship between the iconic Harlem Renaissance painting by Loïs Mailou Jones, Les Fétiches, and Walker Evans’s photographs of African sculptures from MoMA’s seminal 1936 exhibition African Negro Art. It also showcased African sculptures from an internationally renowned collection that had never before been seen outside of Denmark.

Admittedly, this was a complex project, calling on viewers to engage critically on multiple levels. A few of the images were problematic, trafficking as they did in exoticized notions of the Black female body prevalent in the period in which they were produced. But none of the issues the project raised should, in my mind, have been obstacles to the show’s success. Indeed, as an independent curator, I had anticipated and carefully worked through these concerns with a number of well-seasoned individuals in the art world, including prominent African American scholars and curators (David Driskell was on the committee for my dissertation that spawned this project). Nonetheless, despite the excitement the proposal elicited, one museum after another backed away from their initial enthusiastic responses, letting fear of controversy influence their final decision to pass on hosting the exhibition.

Installation photographs of Man Ray, African Art, and the Modernist Lens at The Phillips Collection: All sculptures from the Carl Kjersmeier Collection of African Art, National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen

In contrast, Dorothy Kosinski, the newly appointed director at the Phillips at the time, quickly embraced Man Ray, African Art, and the Modernist Lens, leading to its opening here in fall of 2009. To the museum’s credit, it took on the project with the usual all-hands-on deck enthusiasm characteristic of its efforts. Potential controversies were faced head on; one of the first steps was to organize an advisory board that engaged members of the community in conversations and public programming. Activities were coordinated with Howard University, the David Driskell Center at the University of Maryland, the Millennium Arts Salon, and the National Museum of African Art, expanding the audience for the show to communities beyond the museum’s traditional audience. These efforts paid off. Rather than provoking controversy, the show created dialogues. The involvement of local African American artists and scholars in the programming encouraged increased attendance and participation in related activities from the African American community.

This is not to say, however, that we should just pat ourselves on the back for this endeavor. We might want to investigate what happened to alliances that were forged during this exhibition. Were these initiatives followed up and further cemented? What might the museum have done to maintain relationships with members of the advisory board in a more meaningful way that could have contributed to retaining the expanded audience reach of that exhibition? What did we learn about engaging with complicated material and not backing away from doing difficult work for fear of controversy? And finally, how can we rethink what being a museum of modern art within a global framework means without abandoning our institutional strengths, indeed building on them, as this exhibition did?

As we continue to face the many challenges of an institution striving to live up to commitments to equity and inclusion, perhaps it could be fruitful to mine our history for other examples upon which we can build.