Hello from Donna Jonte, your Phillips at Home host. Thanks for spending time with me and works of art from The Phillips Collection, slowing down to look, think, wonder, and respond creatively.

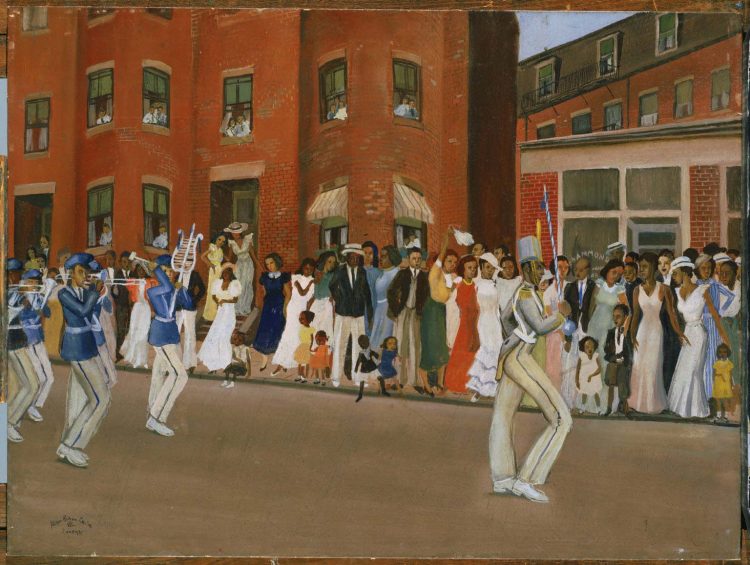

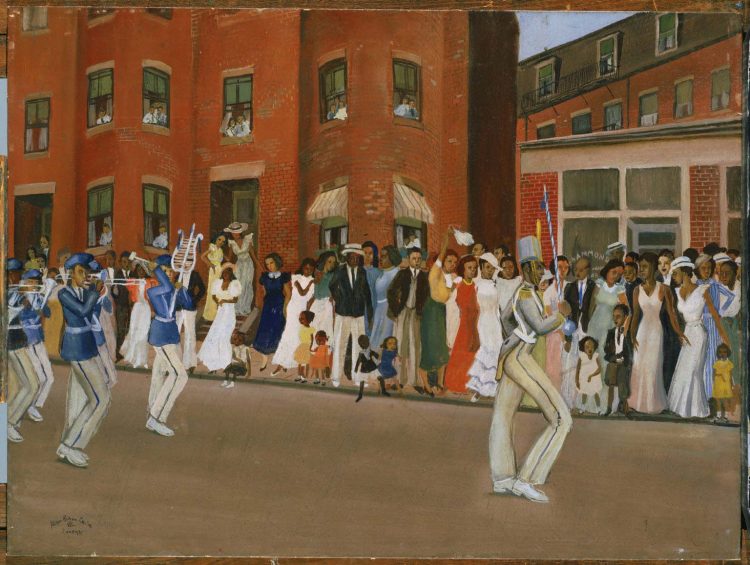

We have practiced a thinking routine called See-Think-Wonder with a still life, a landscape, and a cityscape. Now, using the same mindful-looking technique, let’s explore stories in Allan Rohan Crite’s Parade on Hammond Street and Luca Buvoli’s Picture: Present.

Materials Needed:

Time: 30-45 minutes

Ages: 4+

Allan Rohan Crite, Parade on Hammond Street, 1935, Oil on canvas board, 18 x 24 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1942

Ready to explore? I wonder what the parade is celebrating, don’t you?

(STEP 1) Observe

Find a comfortable place to sit where you and your family members can see Crite’s painting on the screen. Take a deep breath in and exhale slowly.

With your family, look carefully at the image for at least 30 seconds. Let your eyes travel slowly from side to side, top to bottom. Notice what is in the background, middle-ground, and foreground. Notice what takes up the most space in the composition. Notice if there is empty space. Notice the colors, shapes, and lines.

• What did you see? Where did your eye go first? Next? How does the artist lead you through the painting? What colors stand out to you? Lines? Shapes?

• What do you think about what you see?

• What is happening in the street? What is happening on the sidewalk? What is happening in the windows of the red brick row houses? Where is the sky?

• What do you notice about the people in the neighborhood? Does one person especially interest you?

• Do you notice the child who is about to step into the street? How does the artist make sure that we can see the children clearly? Why might he have done that?

• What might the weather be like?

• What is the mood of this painting? What do you see that makes you say that?

• How does the painting make you feel?

• Does this painting remind you of a place that you have visited with your family?

• What do you wonder about this place, the artist, and his process?

• What might the marching band’s music sound like? It makes me think of the Treme Bass Band from New Orleans. Do you think it matches the mood in this painting?

Thank you for sharing your observations and ideas about Parade on Hammond Street with your family.

(STEP 2) Get to know the artist

Allan Rohan Crite (born North Plainfield, NY, 1910; died Boston, Massachusetts, 2007) loved this neighborhood in Boston called Roxbury, where he lived most of his 97 years, carrying his sketchbook everywhere. Describing himself as “an artist-reporter, recording what I saw, “ he stated: “I made these drawings . . . simply to show Black people as . . . human beings that had their loves and their distresses, their joys and happiness and sorrows—just plain, ordinary people. So I made all these different street scenes with the horse carts, the vegetable man, the fish man; or people gossiping, children playing in the streets or the playground—all of these sort of homely things.” (Read his full Smithsonian Archives of American Art oral history interview)

In 1998, in an interview with the Harvard Extension School Alumni Bulletin, he said: “I am a storyteller of the drama of man. This is my small contribution—to tell the African American experience—in a local sense, of the neighborhood, and, in a larger sense, of its part in the total human experience.”

Crite was not only a painter, draftsman, and printmaker, but also an author, librarian, and publisher. He had a day job, too! For 30 years he worked as an illustrator for the Boston Naval Shipyard. Filled with curiosity, he never stopped learning. At an early age his mother encouraged him to draw and paint, and he took art classes at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Massachusetts School of Art, and Boston University. Later he focused on history and the natural sciences, earning a Bachelor of Arts from Harvard University and an honorary doctorate from Suffolk University in Boston. That is a lot of education! Does Allan Rohan Crite inspire you to become an “artist-reporter”?

(STEP 3) Extend the story

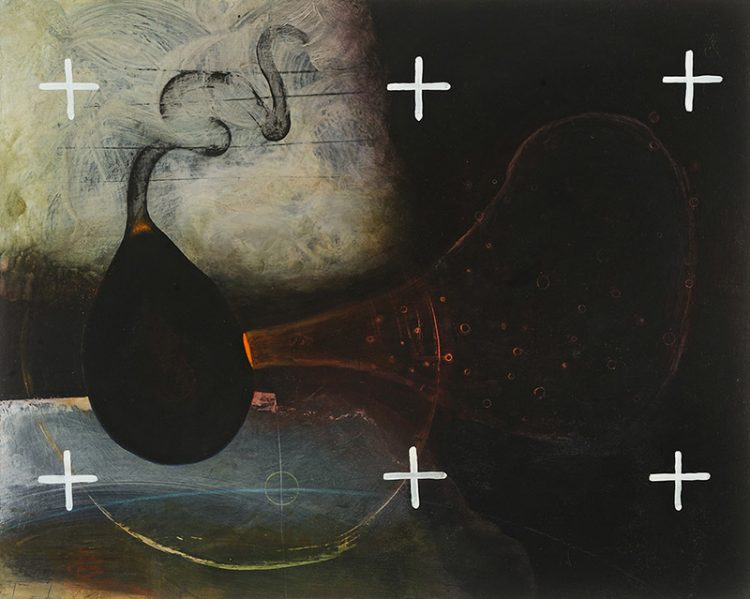

Are you ready to extend the story we found in Parade on Hammond Street? But first, let’s look at a more fantastical story by another artist—Luca Buvoli.

New York-based artist Luca Buvoli (born Brescia, Italy, 1963) invented a story based on artwork in The Phillips Collection, just like we are doing now. When Buvoli was a child he loved to read comic books and create his own. Guess what? As an adult he still does! He made a series of artworks as part of the Phillips’s Digital Intersections contemporary art projects. Picture: Present is the most recent episode from the artist’s Astrodoubt and The Quarantine Chronicles series that features tragicomic visual narratives commenting on the covid-19 health and social crisis. The 12 scenes, which were unveiled on the Phillips’s website from July 20–August 7, will be available on the website through December 1, 2020.

Like Crite, Buvoli is trying to capture the human experience in his illustrations:

Buvoli said: “Through Astrodoubt, and particularly in this opportunity to interact with the Phillips’s collection, I have enjoyed the pleasure of experimenting and playing with time travel, compositions, words and images, and stream of consciousness. I developed these stories to be used as a tool of amusement, reflection, and relief during the pandemic.” Where else do you think Astrodoubt has traveled?

Thinking about Picture: Present, let’s turn back to Parade on Hammond Street. If you stepped into the picture:

- Who will you be? A member of the marching band? The child in the middle of the sidewalk, wanting to step into the street to join the marching band? A person in a window looking down at the parade? Maybe you are not a person but a bird perched on a roof or flying in the blue triangle of sky! A musical instrument, perhaps the glockenspiel? One of the row houses that has sheltered many families?

- What do you think happened just before this scene?

- What might happen next, when the parade moves down the street? As a character in the story, what will you do next?

Your story can be funny, silly, happy, sad, dreamy, realistic, or fantastical—whatever you wish! You are the storyteller.

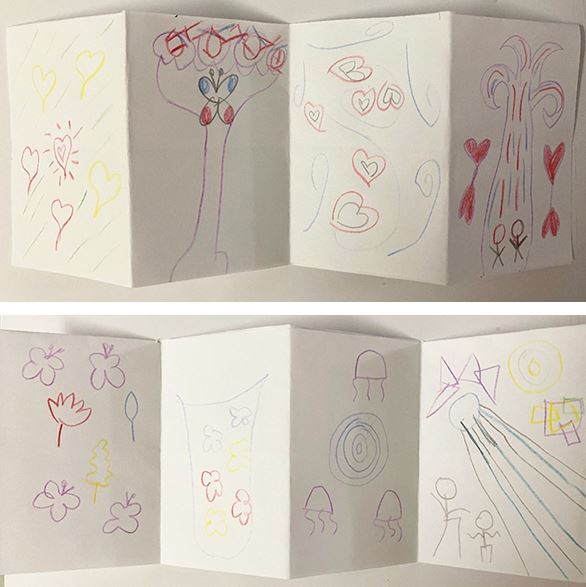

(STEP 4) Create an accordion book

Let’s fold one piece of paper into an accordion book for your story. Here are instructions from the National Museum of Women in the Arts, a museum in DC that has an impressive collection of artist’s books in its library. An accordion book opens and closes like the musical instrument. Do you think that is a good choice for a book about a marching band in a parade?

When you finish your story, don’t forget to write the title and the author’s name (that’s you!) on the cover.

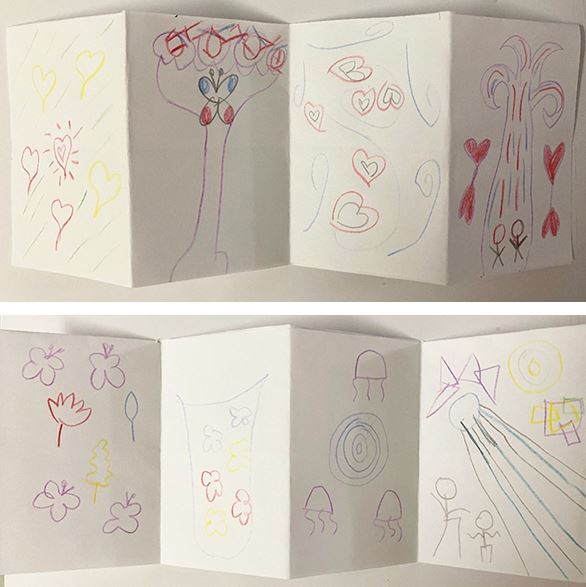

By Carina Araujo, age 8, Music and Dance, two-sided accordion book in response to Parade on Hammond Street. Carina’s story shows that “there is music and dance everywhere.”

Thank you for celebrating community and exploring Allan Rohan Crite’s Parade on Hammond Street. Please share your books with us! Email photos to: djonte@phillipscollection.org