The Phillips Collection galleries have been dark and empty and our staff and visitors have been missing our beloved collection. In this series we will highlight artworks that the Phillips staff have really been missing lately. Manager of Museum Evaluation & Data Analysis Kristen Paral on why she misses Helen Frankenthaler’s Canyon.

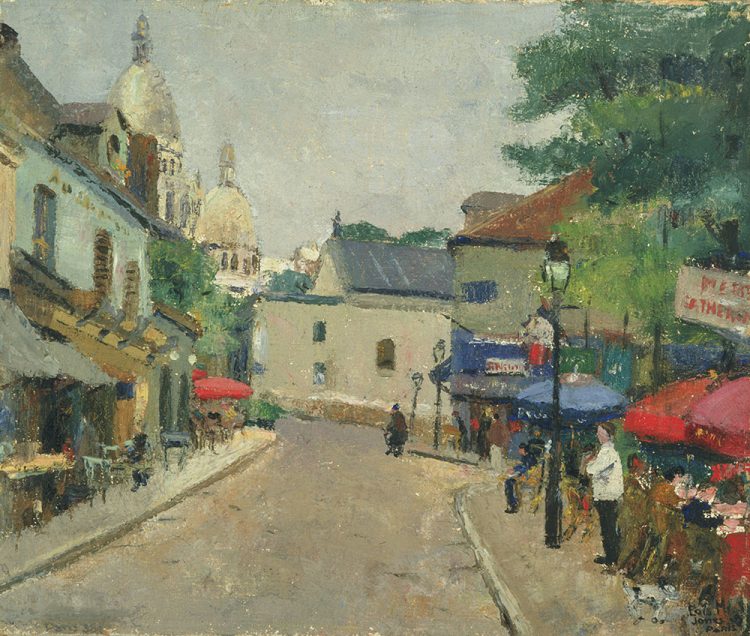

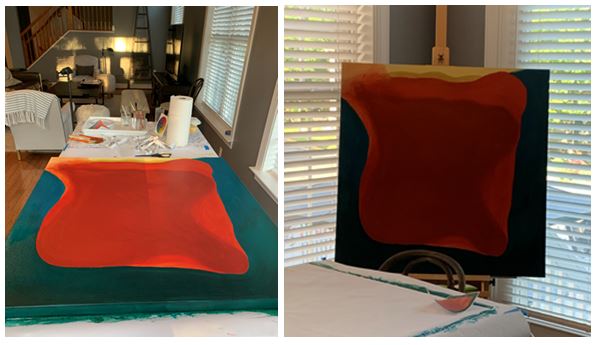

(LEFT) Helen Frankenthaler, Canyon, 1965, Acrylic on canvas, 44 x 52 in., The Phillips Collection, The Dreier Fund for Acquisitions and funds given by Gifford Phillips, 2001 (RIGHT) My re-creation of Frankenthalter’s process

Have you ever missed something so much that you tried to re-create it? When the pandemic hit, I found myself longing for, and trying to re-create, many aspects of my pre-COVID life. I missed my friends and so I arranged Zoom happy hours, which were unsatisfying compared to in-person conversations. I craved for all my favorite restaurant staples and so I learned to cook my own edition of crab cakes, refried black beans, crusted flounder, miso soup, and Greek hummus. Finally, and most poignant, I missed being surrounded by art.

I work at an art museum not only because I enjoy art, but because I believe it is central to our human experience. There is much that I can live without, as this pandemic made apparent, but I cannot live without art.

Within one week of the quarantine beginning, I kept glancing at an empty wall in my bedroom. I needed more art in my life and Helen Frankenthaler’s Canyon kept popping into my mind. So, like my favorite restaurant foods and happy hours with friends, I decided to re-create it.

Frankenthaler used her trademark soak staining technique to create Canyon in 1965. Soak staining is a combination of Jackson Pollock’s pouring technique with Frankenthaler’s innovative method of significantly diluting oil paint pigments with turpentine. Together the techniques yield an ethereal, watercolor-like effect.

My makeshift studio

The first challenge I faced in beginning the project was figuring out how to soak stain using acrylics; I couldn’t use fume-emitting oils paints in a studio space shared with children and pets. Next, I needed to set up a studio space. Frankenthaler created her artwork on the floor, where she poured and, pushed her diluted pigments into glorious abstract formations, often representing landscapes of the seaside near her studio in Provincetown, Massachusetts. I tried placing my canvas on the floor like Frankenthaler, but my back and knees ached; plus, I couldn’t keep my dogs away! So, I set up my studio on a table instead and completed a couple of studies. This experiment reiterated the point that to truly capture the effect of Canyon, the canvas must be laid flat, as mixing paint on canvas with a brush did not yield the signature of effect of Frankenthaler’s soak staining.

The first time that I poured diluted paint on my canvas, chills went down my spine. It felt all wrong! I quickly grabbed a paper towel in a panic and worked to rescue my canvas, but my frenzy dissipated as the magic began.

My experiment pouring diluted paint on a flat canvas.

I pushed and pulled the paint with a palette knife and paper towel. Suddenly the yellow blob of paint began to transform. I rushed to mix and dilute the red-orange color and poured it on the center of the canvas. Once again, I felt like I ruined my painting and so I returned to controlling the process with paint brushes. I alternated back and forth between the two techniques and somewhere along the way, an amalgam of Frankenthaler’s style with my own emerged from the swirls of paint.

Looking at the painting on the table versus on the easel.

I relished the crispness of my clean lines and divisions of colors, but admired Frakenthaler’s ability to make colors float together with seeming intention using soak staining. However, this edition of my painting was unbalanced and I didn’t understand why until I changed my perspective. I propped the painting up on my easel and the solution immediately came to me.

My version of Canyon was too controlled. With each harsh transition in color that I created by using a paintbrush and mixing on canvas, I forced myself to dilute pigment and pour it directly on the canvas to soften the edges. The process of pouring became more natural feeling as I worked. Finally, the painting was complete. But it wasn’t a true replica of Frankenthaler’s, nor was it an original artwork of mine. It is, instead, a process piece representing a journey of healing inspired by art.

My final piece!

I don’t like letting go of control and the pandemic has been testing my sense of having dominion over my life. I clung to my preferred methods of painting because I needed to make something work the way I expected it to. By forcing myself to use Frankenthaler’s soak staining method, I found peace in chance. I found truth in what is, instead of what I can make happen. I discovered a piece of myself that wanted to just let go and accept beauty wherever it can be found.

For now, this journey continues at home and I look forward to the day that it extends back into museums. Until then, I will continue to miss Frankenthaler’s Canyon.