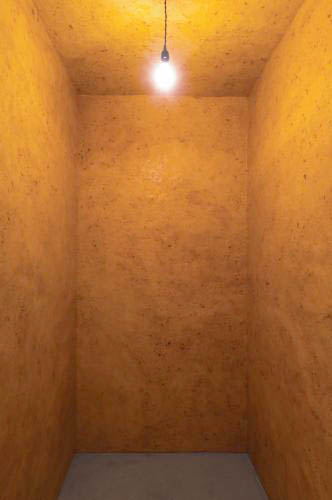

The Phillips Collection galleries have been dark and empty and our staff and visitors have been missing our beloved collection. In this series we will highlight artworks that the Phillips staff have really been missing lately. Manager of Teacher Initiatives Hilary Katz on why she misses the Wax Room.

The Laib Wax Room at The Phillips Collection. Photo: Lee Stalsworth

Wolfgang Laib’s Wax Room immerses us in a space covered in beeswax; the sights, smells, and practically the taste consume our senses. We are transported inside a beehive, but instead of swarming bees, we find ourselves. Instead of dripping honey, we find a solitary hanging lightbulb. Instead of hexagonal honeycombs, we find smooth layers of hardened beeswax.

But what happens when we cannot physically walk inside works of art, such as the Wax Room? What happens when we can’t smell—in this case the beeswax—through our digital devices? How can site-specific, immersive artworks be experienced from the comfort and safety of our homes?

Museums should always prioritize accessibility; now, the public health crises of covid-19 and racism have intensified the need for accessibility. Covid-19 has led to the closure of the physical museum space, forcing us to find alternate ways of opening our doors. Racism, flagrant throughout America in 2020 and the past 400 years, has incited protests and momentum in the Black Lives Matter movement, demonstrating how urgent it is for us to make our spaces accessible and provide a platform for reflection and action. As a museum educator, I aim to increase access to the museum in everything that I do. With my background educating through contemporary art, I relish teaching through immersive artworks—a daunting task to do while we’re at home.

The full title for the installation—Wax Room: Wohin bist du gegangen – wohin gehst du? (Where have you gone – where are you going?)—adds layers of complexity. Who is the “you” to which the title refers? Is it the bees? Is it someone the artist seeks? Is it us—the viewers, the participants?

Does Laib want us to consider how essential bees are to our survival, yet climate change threatens them? Alternatively, does the title serve as a metaphor for the people that come and go? Perhaps the singular lightbulb demonstrates the emptiness and loneliness one feels when someone is “gone.” Since only two people can fit in the Wax Room, the experience is solitary, something we can relate to all too well right now.

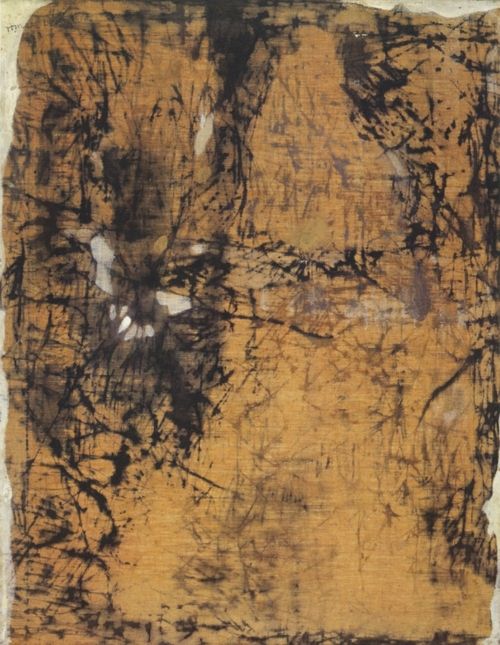

Laib engaged in a ritualistic process to melt over 440 pounds of beeswax (at an even temperature to ensure a consistent color) and apply the layers to the walls and ceiling, using a spatula, spackle knife, electric heat gun, and warm iron. Photo: Rhiannon Newman

Yet the Wax Room inspires hope. You can practically taste sweet honey through the beeswax emanating from every surface of the room. Laib’s meditative installation process, combined with the intimate size of the space (6 x 7 x 10 ft.), allows us to enter into another world upon stepping into the Wax Room.

Just as bees are interconnected to human survival, we are all interconnected through our collective goal to survive this pandemic (of both disease and systemic racism). Art can provide a moment of solace, distraction, and hope during difficult times. Although I continue to dream of the days when I can walk by a physical work of art, allowing my senses to be engulfed, I have found other ways to savor those memories. Now is the time to tap into our imagination and bring to life the Wax Room from home: stir honey into a glass of steaming hot tea, eat a bowl of Honeycomb cereal, smell a beeswax candle, grab a spoonful of sticky and gooey fresh honeycomb, sit and meditate underneath a single lightbulb, go for a walk outside and look for a bee pollinating a flower.