Associate Conservator Patti Favero explains Moira Dryer’s unique choice of paint medium.

The works on display in Moira Dryer: Back in Business are remarkable for the artist’s distinctly individual style which includes unique structures, vibrant colors, and evocative paint layers.

Moira Dryer, The Debutante, 1987, Casein, lacquer on rubber, wood, 48 in. diam., Collection of Marguerite Steed Hoffman © Estate of Moira Dryer

As we installed the show in early February, I learned that Dryer’s unique approach extends also to her materials. Many of the works in the exhibition are painted on thin plywood panels, not more than 1/8-inch thick, that are shaped or mounted to come forward off the wall and into the space. One panel is even bent into a free-standing form, while another is combined with found objects in a sculptural assemblage. But it was Dryer’s unusual choice of casein as a paint medium that really interested me.

What is Casein?

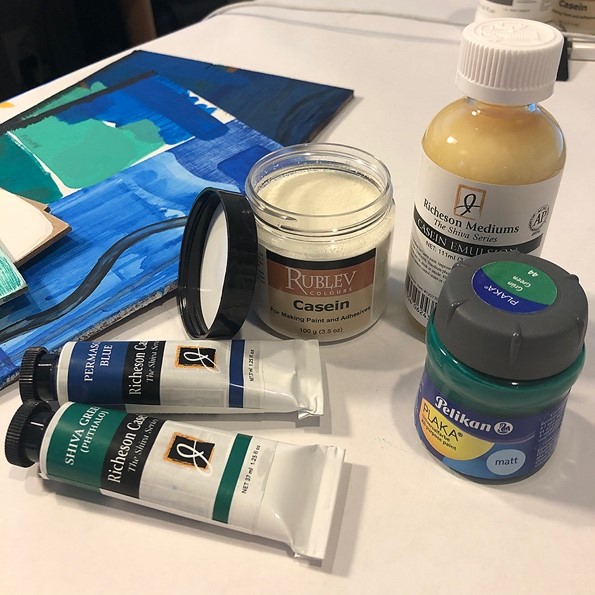

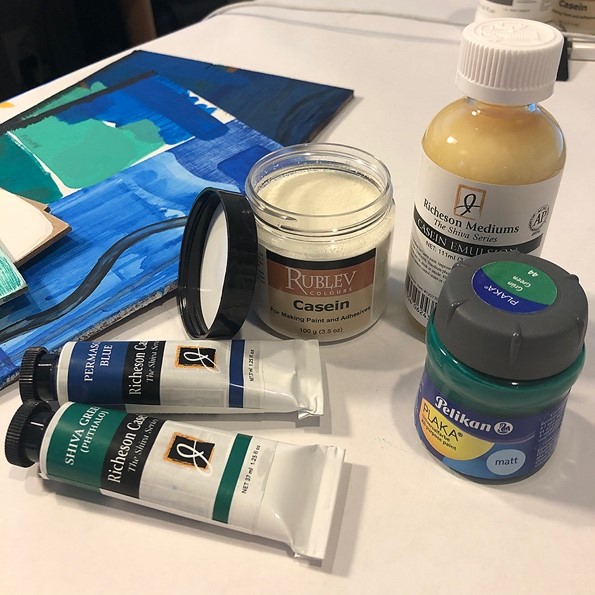

Samples of casein paints and mediums. Left to right: Richeson “Shiva” casein tube paints, pure casein powder from Rublev Colours (“For Making Paint and Adhesives”), Richeson “Shiva” casein emulsion medium, and Pelikan Plaka “All-purpose paint.”

Casein paints are based on caseinate, a protein found in milk. To make casein, the protein is separated from the whey and butterfat, then an alkaline material is added to break it down and allow it to mix with water. Casein has been used in a variety of forms for centuries. One medieval manuscript describes washing milk curds until the water runs clear, then mixing with quicklime into “cheese glue” for joining panels for altars and doors. [1] Another recipe for “milk paint” mixes casein powder, soaked in water, with Borax (sodium tetraborate) to make a water-thinned paint medium. [2]

Homemade casein will spoil after a few days, and it can be difficult to get consistent mixtures. Fortunately, artists have been able to buy stable, commercially-made casein paints for decades. This is probably the most reliable option and most likely what Dryer did.

Why Casein?

Casein is commonly associated with commercial artists and decorative painting—it is not a paint typically used by fine artists (with notable exceptions [3]). So why did Moira Dryer paint with casein?

In interviews, Dryer discussed how her early work building theater sets and props influenced her art: “I was always very transfixed by the play before the actors came on or after they left the stage. That was my job and that was what I focused on. The lighting would be there, the tension and the audience would be there, but not the actors. Those props had an incredibly provocative effect.”[4]

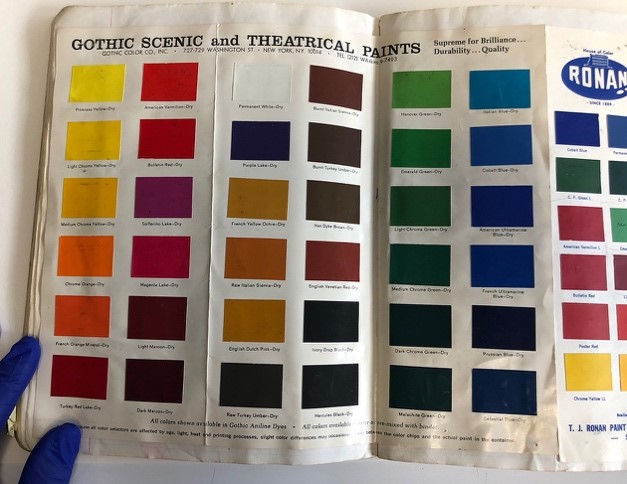

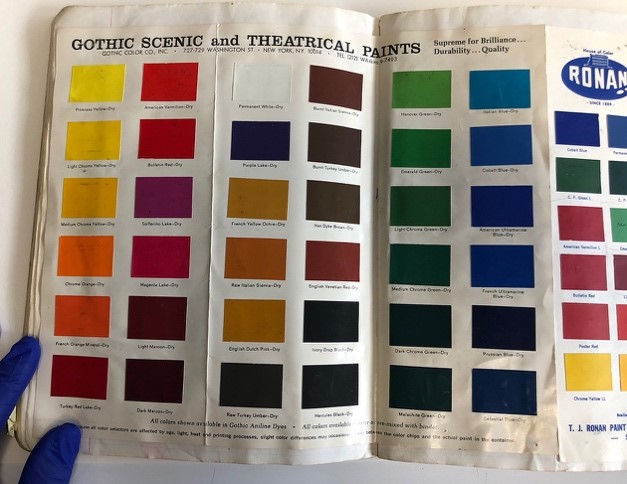

Dryer saved this color card for Gothic Scenic and Theatrical Paints in one of her notebooks. Gothic Color Company, Inc., made paints especially for theater and other scenic artists. They sold pure pigments and a variety of binders, along with a line of “Casein Fresco Colors” specifically developed for television studios.

While she doesn’t mention casein specifically, Dryer’s use of this medium also seems to come out of the scenic artist’s tradition. Scenic artists had particular criteria for their paints, including ease of use, vibrant color, and a flat, non-glossy surface that would evenly reflect stage lighting.[5] Casein paints have many of the properties valued by scenic artists. They can be thinned with water, which makes them practical and relatively safe to use, and they dry quickly. A high pigment load gives vivid color even when the paint is diluted, and the paint dries to a matte, even surface.

Painting with Casein

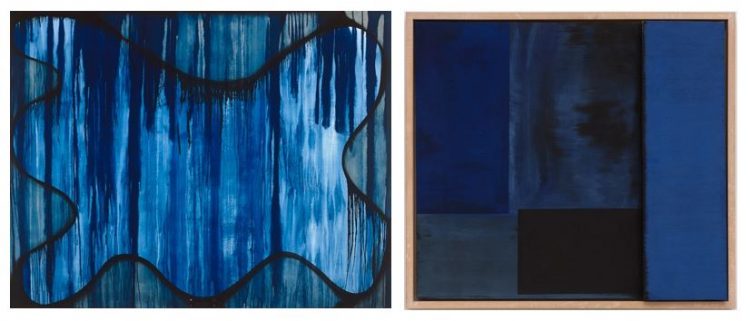

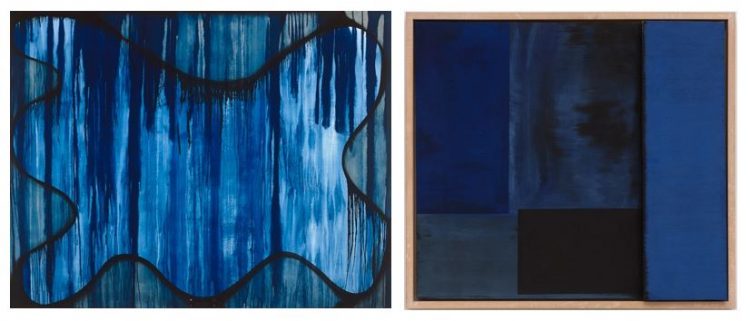

Casein dries quickly, but unlike acrylic the dry paint can still be manipulated somewhat. Dryer used these qualities to explore a number of visual effects in her striking compositions, such as the diaphanous washes of Suburbia or the opaque layers and dry-brush effects in Group Portrait.

(LEFT) Moira Dryer, Suburbia, 1989, Casein on wood, 66 x 84 in., Collection of Michael Straus (RIGHT) Moira Dryer, Group Portrait, 1985, Casein on wood, 24 x 26 1/2 in., Collection of Nancy Morawetz © Estate of Moira Dryer

To learn more about what it’s like to work with casein, I made small mock-Moira Dryer paintings. I experimented with both casein and also Flashe acrylics, which Dryer used near the end of her short career. I explored techniques seen in some of her paintings, such as sanding or layering over dry paint, and creating layered washes to approximate her surfaces.

Mock-up panel, 8 1/4 x 7 x 1/8 in., primed with Liquitex acrylic gesso and painted with Richeson “Shiva” Casein paints, in blue at right and dark green at lower left, and Flashe acrylic color in blue and light green at upper left

The casein was a lot of fun to work with. I tried using it straight from the tube and thinned, with water, to different strengths. Because of the heavy pigment load, the paint doesn’t lose its brilliance when diluted, and a little goes a long way. The dry casein was readily soluble again in water. This allowed me to easily create a series of wash and drip effects. When I tried to re-create Dryer’s even, dark veil of black over blue in Suburbia, however, I found it was difficult to avoid disturbing the thin blue layers beneath the black.

Making mock-ups is usually an exercise in appreciating the artist’s mastery of their materials, and this experiment was no exception.

(LEFT) Detail of Suburbia, bottom center (RIGHT) Detail of Mock-up panel, upper right corner

Notes on Preservation

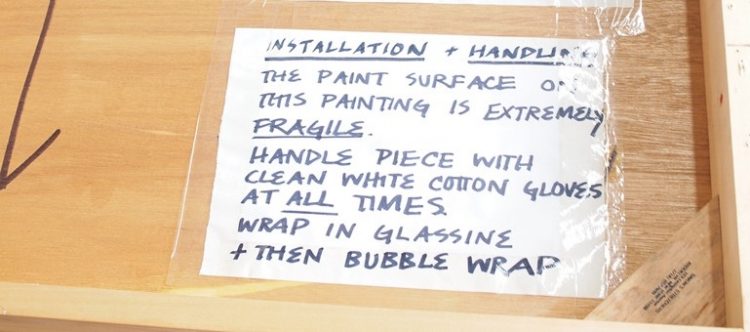

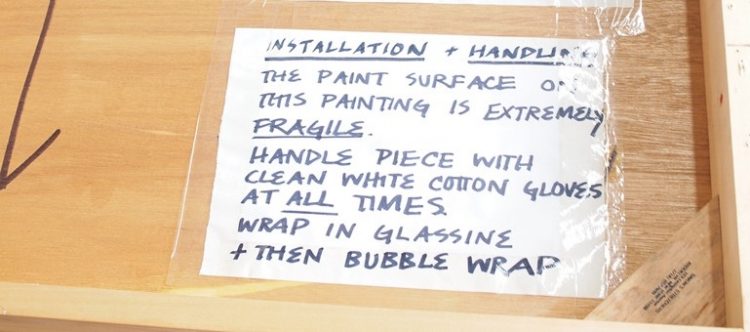

Although casein has a reputation for being durable, casein paint surfaces are in fact quite fragile. They are susceptible to fingerprints, scuffs, and burnishing if not handled carefully. Ideally (and contrary to the artist’s instructions) they would be stored and transported with nothing touching the surface. The dried paint also remains sensitive to water to some degree, despite what is written. A water droplet left on the surface will leave a tideline, and even a carefully rolled conservator’s swab can pick up color.

Moira Dryer’s handwritten notes on installation and handling, which are found on the backs of many of her paintings

Notes

[1] Theophilus, On Divers Arts, John G. Hawthorne and Cyril Stanley Smith, trans. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. 1979.

[2] Kremer Pigments Catalog: “Raw Materials for Fine Arts, Conservation, Woodfinishing, Design,” New York: Kremer Pigments, 2002. P58.

[3] See Elizabeth Steele “The Materials and Techniques of Jacob Lawrence” in P. Nesbett and M. DuBois, eds., Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence. Seattle: University of Washington Press, in association with Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation, 2001. 247-265.

[4] Moira Dryer in conversation with Klaus Ottmann, Journal of Contemporary Art, Spring/Summer 1989

[5] Gothic Color Company, Inc., Scenic Artist’s Handbook, ca. 1965.