Eliza Lafferty, an intern with the Major Gifts and Director’s Office, discusses the abstract works of Romare Bearden, an artist featured in Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition, on view at The Phillips Collection through January 3, 2021. This post is based on a seminar paper with Professor Elizabeth Prelinger at Georgetown University and was awarded the Misty Dailey Award in Art, Diversity, and Healing.

Romare Bearden (1911-1988) is highly acclaimed for his collages from the American Civil Rights movement. Although a celebrated African American artist, scholarship often forgets to account for the entirety of his art historical contributions—including his abstract works that do not directly engage his race. The omission of Bearden’s abstract paintings from the Western canon is a result of systemic racism in the art world; many abstract paintings by African American artists are forgotten, unsuccessful in the art market, or assumed to reference trauma and/or racial struggle. To combat the common erasure of abstract works by African American artists, scholarship must engage Bearden’s abstract works in conjunction with his collages.

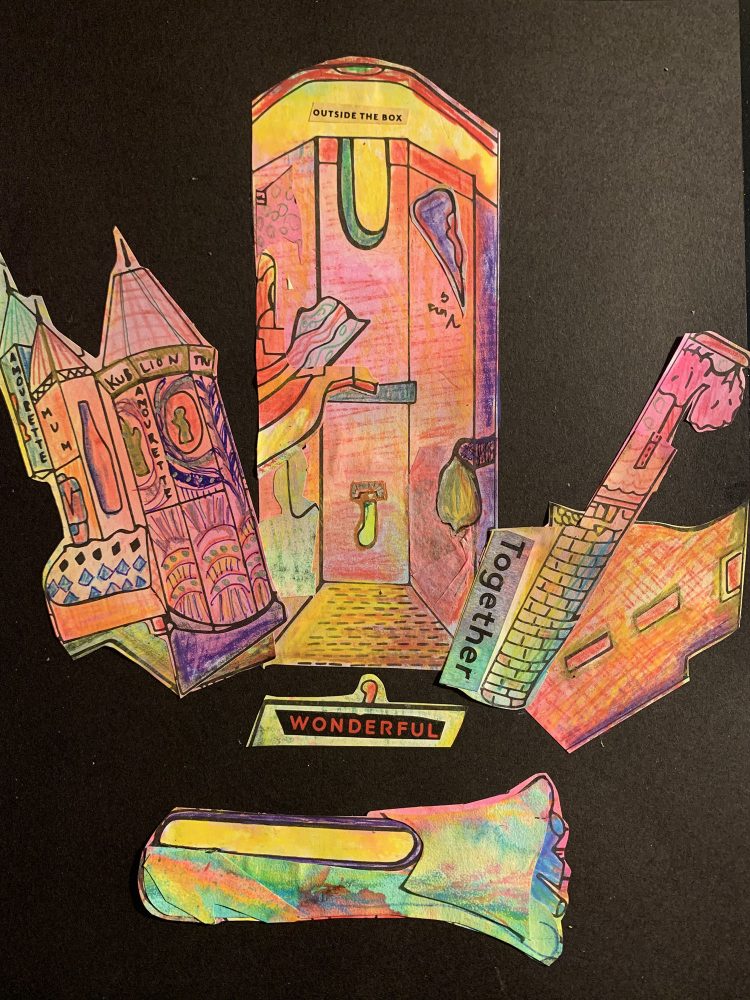

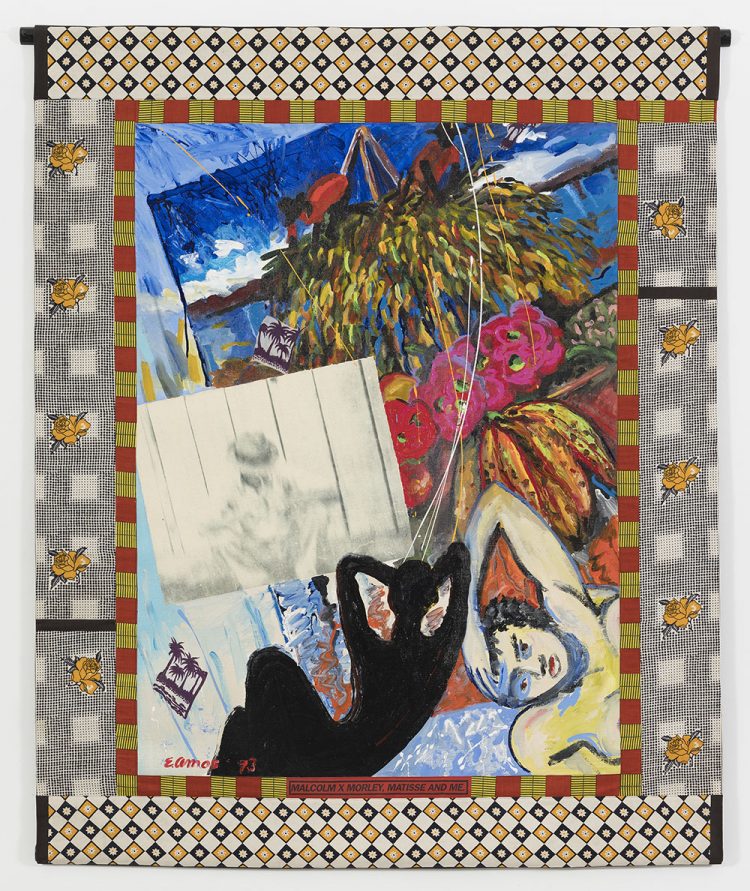

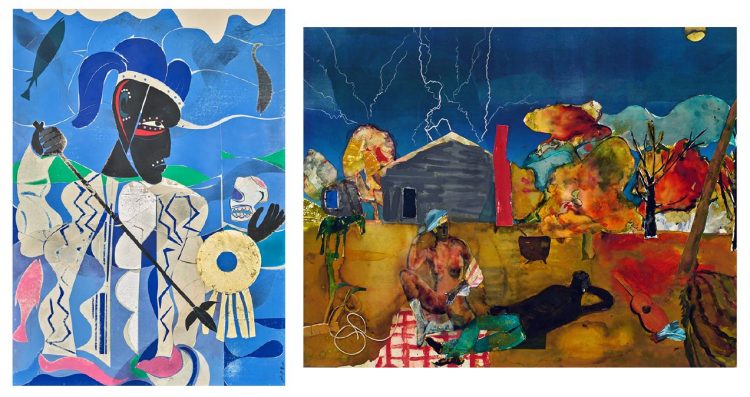

Collages are Bearden’s signature style and elevated him to fame from 1963 and 1964. His use of the collage began simultaneously with his involvement in the Spiral group of African American artists operating during the Civil Rights Movement. Bearden’s collages address narratives surrounding Black movement, migration, and diaspora. Riffs displays two collages by the artist—Mecklenburg Autumn: Heat Lightning Eastward (1983) and Odysseus: Poseidon, The Sea God-Enemy of Odysseus (1977). Mecklenburg Autumn echoes Edouard Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass (1862) and depicts a black couple, with the woman’s face as an African mask, picnicking outside a Southern home.[1] Odysseus adapts Homer’s Odyssey to chronicle the Great Migration. Elements of the collages are abstract: in Mecklenburg Autumn, Bearden paints nebulous foliage in the background and simple blocks of gray and red to detail the house; Bearden also employs a variety of shapes and vibrant color blocks in Odysseus. Still, the figuration in the collages contrasts the purely abstract canvases Bearden painted earlier in his career.

(LEFT) Romare Bearden, Odysseus: Poseidon, The Sea God-Enemy of Odysseus, 1977, Collage on fiberboard, 43 3/8 x 31 3/8 in., The Thompson Collection, Indianapolis, IN; (RIGHT) Romare Bearden, Mecklenburg Autumn: Heat Lightning Eastward, 1983, Collage and oil on fiberboard, 31 x 40 in., Collection of Ginny and Conner Searcy

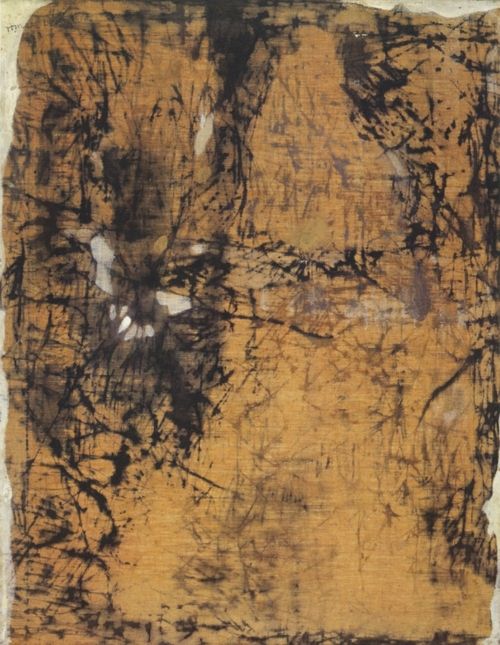

While scholarship aptly recognizes Bearden’s collages, it rarely acknowledges his work that does not engage identity, including his abstract creations from 1950-1964. Bearden’s Old Poem from 1960 divorces Black narratives and instead finds inspiration from Chinese Zen paintings. During an interview in 1972, Bearden remarked how he found inspiration in Chinese classical painters’ use of space to direct gazes across the canvas. He adopted the technique in Old Poem and provided vacant, warm, yellow space near the bottom horizontal line of the canvas.[2] Old Poem is one of Bearden’s many abstract pieces—all of which are moreover forgotten from public memory. In 2017, The Neuberger Museum of Art in New York hosted the first public showing of many of Bearden’s abstract watercolor paintings, mixed media collages, and stain paintings; prior to the exhibition, most paintings were in storage.[3] Bearden’s abstract works, which disengage his identity, should be absorbed into the greater conversation of his career.

Romare Bearden, Old Poem, 1960, Oil on linen, Private collection

Analysis of Bearden’s portfolio reveals the expectation for African American artists to create narrative, identity-specific pieces. His fame is predicated on attaching raced identity to artists, creating “African American Art.” While Bearden chose to engage and disengage his Blackness in certain works, we must seek to understand the whole artist—not just the parts that appeal to Western expectations. Modern scholars should address Bearden’s wide-ranging portfolio. Memory of Bearden’s work must not flatten his contributions but engage his dynamic shifts in style and inspiration, and in the process, reimagine the depths of his contributions to the Western artistic canon.

[1] Adrienne L. Childs, Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition (Washington, DC: The Phillips Collection; New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2020), 106.

[2] Mary Schmidt Campbell and Sharon F. Patton, Memory and Metaphor the Art of Romare Bearden, 1940-1987 (New York: Studio Museum in Harlem, 1991), 36.

[3] Natalie Espinosa, “Romare Bearden: Abstraction,” American Federation of Arts, October 4, 2019, https://www.amfedarts.org/romare-bearden-abstraction/.