This is a multi-part blog post; read Part 1 here.

Though we usually associate abstraction with the medium of painting, Aaron Siskind’s photograph Chicago 30 is decidedly abstract.

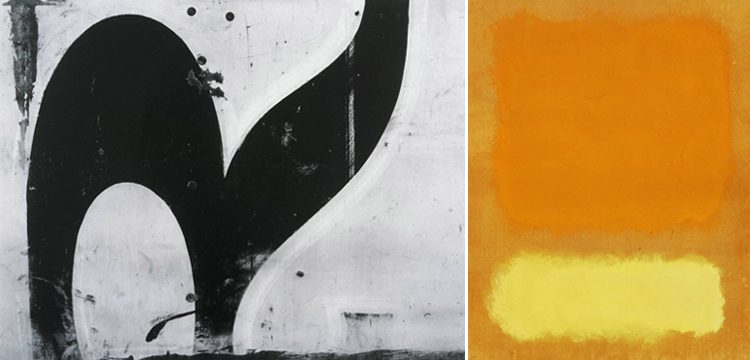

(left) Aaron Siskind, Chicago 30, 1949. Gelatin silver print, 13 3/4 in x 7 1/2 in, The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Gift of the Phillips Contemporaries, 2004 (2) Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1968. Acrylic on paper mounted on hardboard, 23 13/16 x 18 11/16 in. Gift of the Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc., 1985 © 2005 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Can a photograph be painterly? If it fools the eye enough, can it have the same visual appeal of a painting? Of course there are key differences between the mediums of painting and photography, but for centuries the aim of painting was to trick the viewer; to create something so real and present that the viewer forgot that it was simply paint on canvas. The advent of photography and the emergence of modernism and then abstract expressionism helped shift the art world away from exact reproduction of the physical world. Compared with Mark Rothko’s untitled 1968 abstract expressionist painting (above right), the flourish of black in Siskind’s work appears almost like a brush stroke while Rothko’s appears devoid of the artist’s hand.

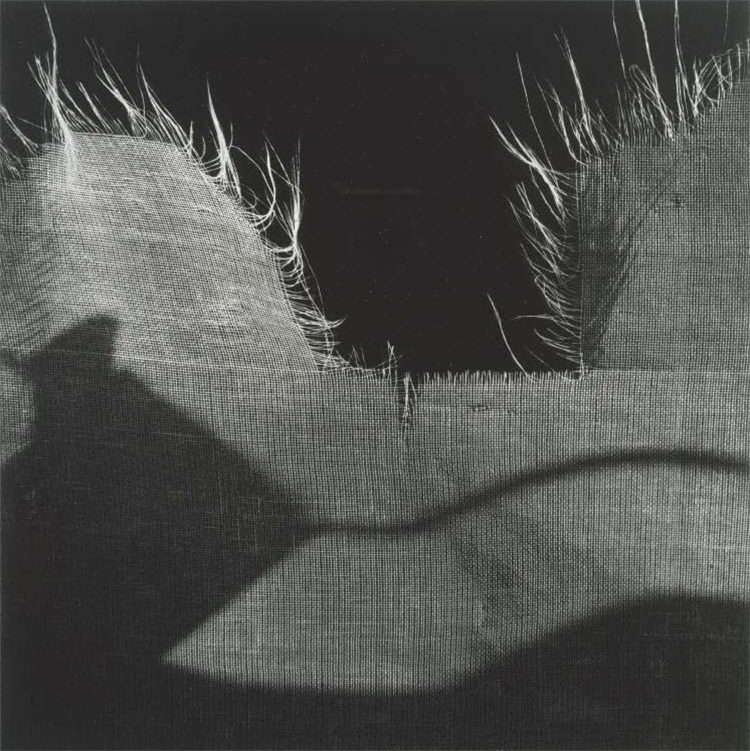

Aaron Siskind, Mexican 32, 1982. Gelatin silver print, 20 in x 16 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Gift of Marie M. Martin, 2005

Siskind’s Mexican 32 is also an abstract work, but it contains a hint of context. The identifiable shadow creates a sense of space in the work; the fraying fabric provides texture, as well as a three dimensionality and depth to the photograph (although this depth is lessened by the stark black background).

Siskind explored abstraction through his camera. These works are an important contribution to the abstract expressionist movement, in which Siskind was socially and professionally involved, but these works are also an intimate window into how Aaron Siskind understood and viewed the world around him.

Emma Kennedy, Marketing & Communications Intern