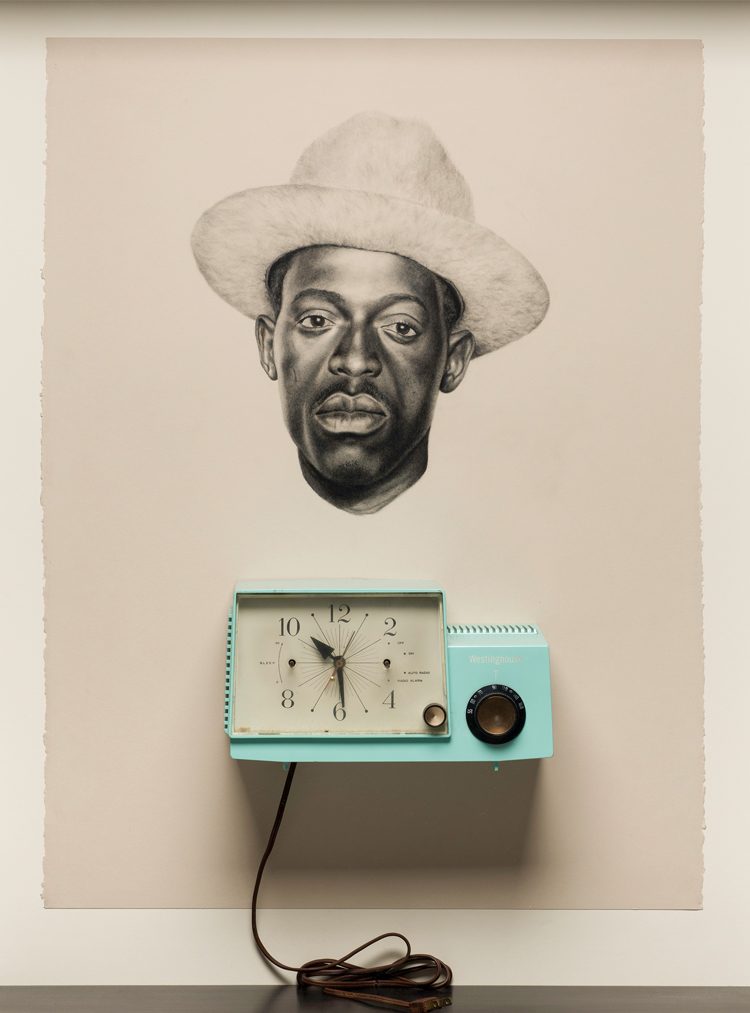

Whitfield Lovell, Kin XXXV (Glory in the Flower), 2011. Conté on paper, vintage clock radio, 30 x 22 3/4 x 5 3/4 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, The Dreier Fund for Acquisitions, 2013 © Whitfield Lovell and DC Moore Gallery, New York

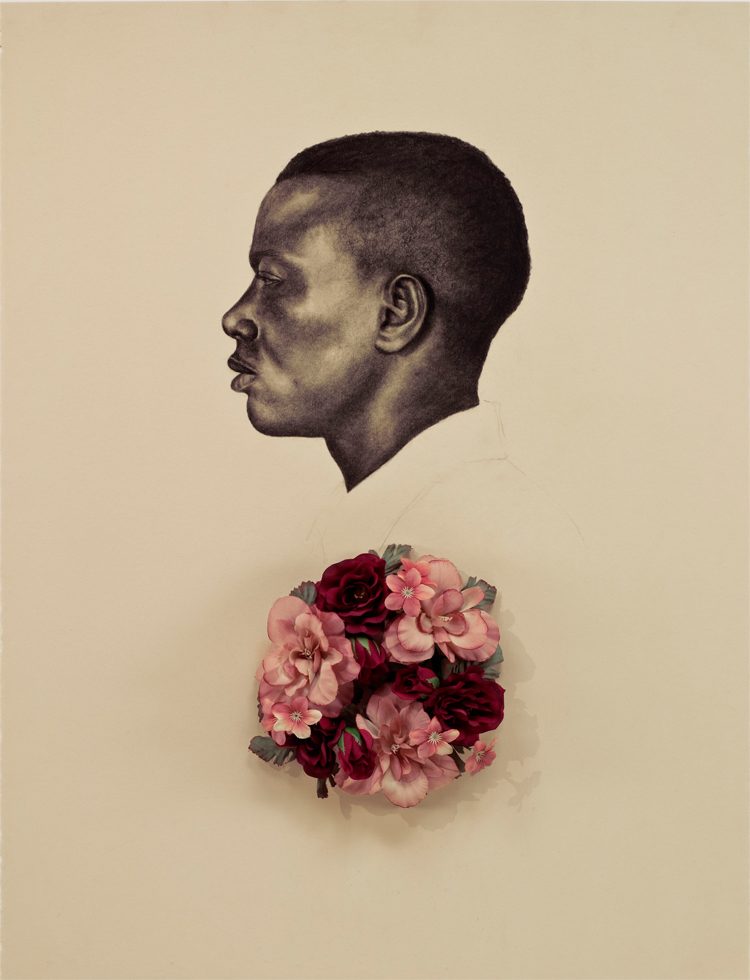

The subtitle of this work by Whitfield Lovell, a recent acquisition for the museum, is “Glory in the Flower,” which references the below poem by William Wordsworth. Why do you think Lovell chose this particular phrase for this work? Why do you think he chose a clock as the accompanying object to this portrait?

Though nothing can bring back the hour

Of splendor in the grass, of glory in flower;

We will grieve not, rather find

Strength in what remains behind;

In the primal sympathy

Which having been must ever be;

In the soothing thoughts that spring

Out of human suffering;

In the faith that looks through death,

In years that bring the philosophic mind.

–William Wordsworth, “Ode on Intimations of Immortality” from Recollections of Early Childhood, 1804

Whitfield Lovell: The Kin Series and Related Works is on view through Jan. 8, 2017.