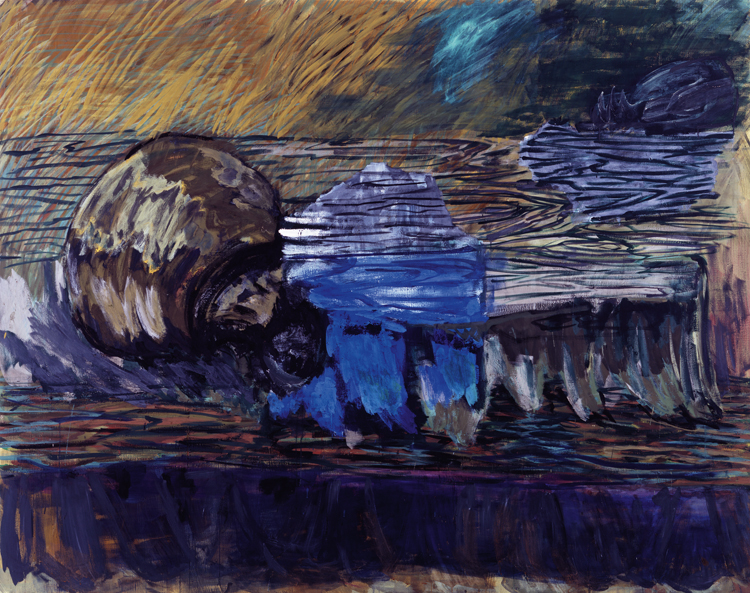

(left) Mathematical Object: Algebraic Surface of Degree 4, c. 1900. Wood, 3 1/8 x 2 3/8 in. Made by Joseph Caron. The Institut Henri Poincaré, Paris, France. Photo: Elie Posner (middle) Man Ray, Mathematical Object, 1934-35. Gelatin silver print, 9 1/2 x 11 3/4 in. Courtesy of Marion Meyer, Paris. © Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2015 (right) Man Ray, Shakespearean Equation, All’s Well that Ends Well, 1948. Oil on canvas, 16 x 19 7/8 in. Courtesy of Marion Meyer, Paris. © Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2015

Above is an example of what you’ll see in Man Ray–Human Equations: A Journey from Mathematics to Shakespeare, opening in less than two weeks. The exhibition centers on Man Ray’s (1890–1976) Shakespearean Equations, a series of paintings inspired by photographs of mathematical models he made in Paris in the 1930s. Within the galleries, you’ll see the original mathematical models, Man Ray’s inventive photographs of the objects, and the corresponding Shakespearean Equation painting displayed side-by-side for the first time.