In anticipation of her installation of her work Contingency on Wall at the Phillips, artist Dove Bradshaw sat down with Phillips blog manager Amy Wike to discuss her artistic process.

Amy Wike: I thought we would begin with you describing your creative process. Generally speaking, from the inception of an idea, how do you begin; what does your creative process look like?

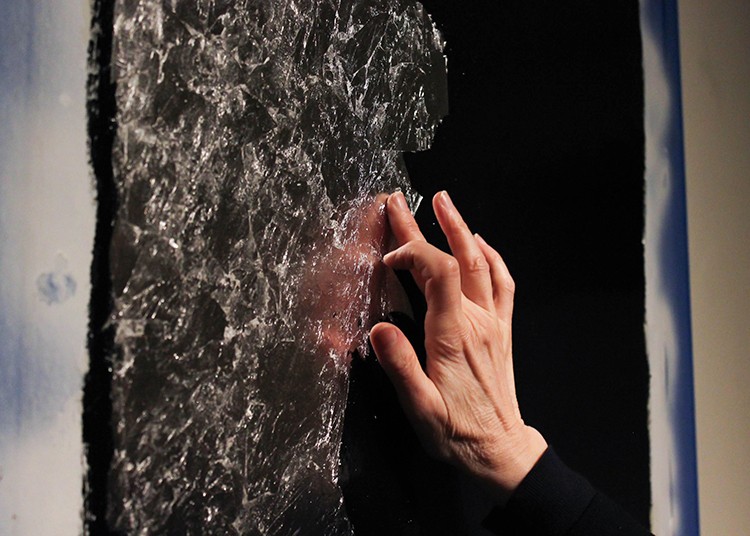

Dove Bradshaw: Wow! What a question. Nearly every idea comes in a different way. For instance, let’s talk about the piece I’m doing here, and how I got the idea . . . In 1984, I covered works on paper with silver leaf and then painted and poured this chemical, liver of sulfur, on it to create phenomenological kinds of images having to do with the topography of the paper; [for example] if it was handmade paper it was rough, it would pool, and so on. And the piece that I’m doing here is a mural. The first time I thought of the idea was in 1988, where I was re-creating an installation of twenty years before Plain Air . . . I had decided to put on the wall rectangles of plaster and of silver leaf. In the end, I didn’t execute it in that piece but that was when I conceived of it and did it later in my studio, my home. And the piece I’m doing here has no chemical, it’s just a skim coat of plaster, then gesso, varnish, and silver leaf, and I leave the leaf to sulfurize in the air. Light, air, humidity, all affect silver. So in the course of a year, you’ll see the changes. The longer it’s up, folks at the museum, the longer you’ll see the changes!

AW: That leads nicely into another question I have, which is: do you ever consider a work finished?

DB: Yeah! Yeah I do. William Anastasi (with whom I have lived with for four decades) titled a whole series of works Abandoned Paintings with Willem de Kooning‘s notion that paintings are never finished, they’re merely abandoned, in mind. However, I do finish work. Unlike writing; I find that you can come in and tweak it, tweak it and tweak it, right? . . . . In painting, I find, rarely do I want to come back and change something.

AW: You’ve worked a number of different mediums and forms—performances, stage design, sculpture—how do these all relate to each other? You did just speak quite well to that, do you have any other examples of that kind of cross-reference in your very different mediums?

DB: Well when I worked for sets, costumes, and lighting with Merce Cunningham, the first piece I used I was influenced by Mondrian. He believed that color should be integrated into architecture not as a decorative element, but as an essential element to the structure and the movement. I thought that this would be great for dance, of course, and by coincidence, there happened to be fourteen different colors in Wall Work II, 1943-1944, where the primaries were on colored cardboard squares of different sizes. There were fourteen dancers in Merce’s company, so it was perfect, it seemed as though the pasta had fallen on the sauce. And so I thought, “Merce will be in grey and the dancers will all be in color.” It made a beautiful pattern; at any moment on the stage, there could be a cluster of five red and one primary blue and mix it up, or just a couple of white accents, and so on.

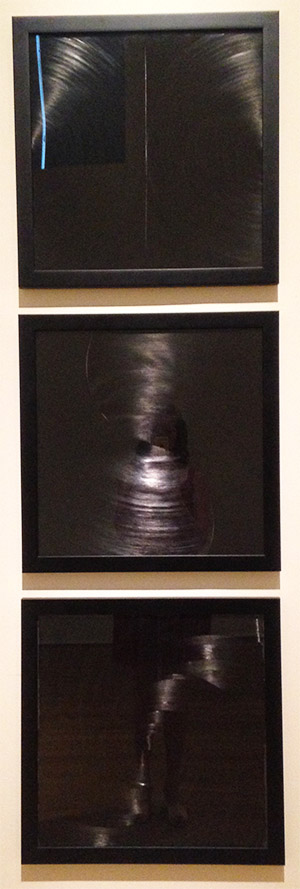

And then after that was my own work, I would transfer whatever I would be thinking of at the moment to a set design. Most notably in Fabrications I had one where I had . . . an inner ear valve and intestines which looked very beautiful because they were a diagram, two spirals, and I had the dancers in [their colored] dresses. The dresses…were in silk and so the swirl of the dresses connected to the spirals of those intestines.