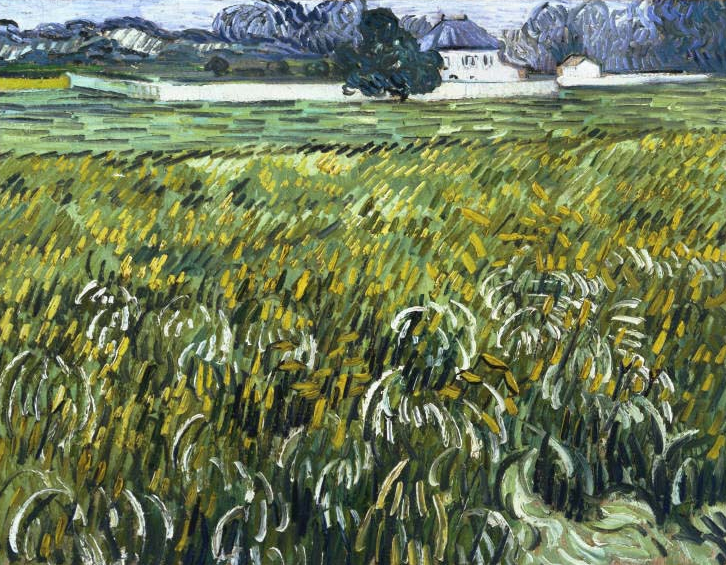

Vincent van Gogh, House at Auvers, 1890. Oil on canvas, 19 1/8 x 24 3/4 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1952

Re-opening the original Phillips house galleries this June allowed the curatorial team to create new dialogues between artists. One of the more surprising, on the surface, is the side-by-side installation of Vincent van Gogh’s House at Auvers, 1890, and Francis Bacon’s Study of a Figure in a Landscape, 1952. Painted more than 60 years apart, these paintings would never be hung together in a traditional, chronological museum installation. Luckily for everyone, the Phillips was founded with the belief that works be hung in conversations with one another regardless of art movement, time period, etc.

Francis Bacon, Study of Figure in a Landscape, 1952. Oil on canvas, 78 x 54 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1955 © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. / DACS, London / ARS, NY 2015

Bacon and van Gogh shared similar mental struggles that manifested themselves in their work. Their respective feelings of anxiety and alienation find parallels not only in subject matter but style. In fact, Bacon admired van Gogh, and it’s safe to assume van Gogh’s brushwork influenced this work in particular.

The high horizon lines that draw your eye back into the pictures along with the staccato brushstrokes of the fields create an almost foreboding sense of dread. In van Gogh’s painting, it seems as though we will never reach the home across the turbulent field. The hope for safety (and, perhaps, sanity) lies in the walled-off home that is almost being pushed out of the painting’s frame, out of view.

In Bacon’s, however, we are being pushed to confrontation with a crouching figure who appears to have just materialized like a hallucination. The open brushwork and the exposed, unprimed canvas leave us nowhere to hide. We are face to face with an embodiment of the artist’s anxiety and psychosis. Is the subject a predator, or someone seeking solitude?

Both paintings seem to be paused in time, a snapshot of each artist’s travails, with no beginning and no end.