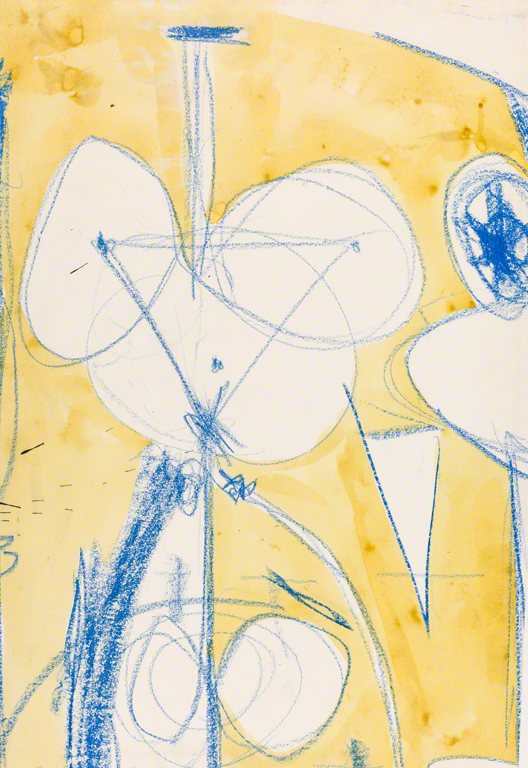

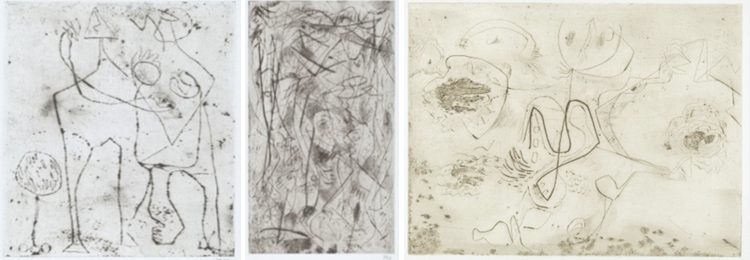

All works: Jackson Pollock, Untitled, 1944/45 (printed 1967). Engraving and drypoint in blown-black on white Italia wove paper. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. (1) and (2) The William Stamps Farish Fund, 2009; (3) Gift of the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, Inc., 2009

In 1930, Jackson Pollock confessed to his brother his frustration that his drawing was “rotten; it seems to lack freedom and rhy[thm].” That changed dramatically in 1944, when Pollock spent several months at Atelier 17, the printmaking workshop where he practiced the Paul Klee-inspired automatic writing taught by Stanley William Hayter. Hayter’s Atelier 17 was a central meeting place for avantgarde artists such as Pollock, William Baziotes, Adolph Gottlieb, and Mark Rothko.

These three works were printed from more than 10 plates that Pollock etched over several months at Hayter’s studio. Hayter, who had seen how the method of automatic drawing had invigorated French surrealist artists, saw the potential to convert more followers among the American abstract artists. He insisted that his acolytes etch directly into the zinc plates without any preparatory sketches and call upon their unconscious to generate line drawings. Hayter’s studio became a rite of passage for many Abstract Expressionists, although it had an especially profound impact on Pollock, who took from the experience an appreciation for spontaneous, nondescriptive line. The emphasis on the physical act of making art set the stage for Pollock’s breakthrough just a few years later to his drip paintings.

This work is on view in Ten Americans: After Paul Klee through May 6, 2018.