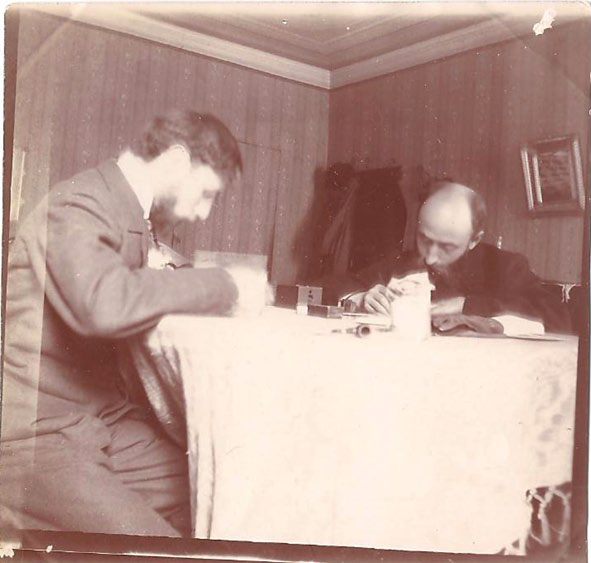

In this photo, taken by Vuillard, note the camera, likely Bonnard's, sitting on the table, pointed at the viewer. Edouard Vuillard, Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard in the dining room, Rue des Batignolles, 1897. Gelatin silver print, 3 1/2 x 3 1/2 in. (9 x 9 cm.). Private Collection.

The biggest idea that I took away from our staff tour of Snapshot: Painters and Photography, Bonnard to Vuillard, was how experimental, private, and exciting the medium of photography was for these artists. They were not photographers, they were painters. They were men with a passion for visual exploration, enchanted by this easy, instantaneous little device, the snapshot camera. They brought cameras into their homes, took them on trips to the beach, set them on tables in restaurants. They took photos of their children sleeping, their lovers’ gazes, themselves reflected in mirrors, their bustling cities. These images were visual diaries of a sort, little notes about the light of the day, the activities, the emotions. They were never exhibited, occasionally traded, often collected in boxes with letters and other keepsakes. This show brings viewers into the life of these seven artists, not just with their intimacy, but with the feeling that these memories could belong to any of us.