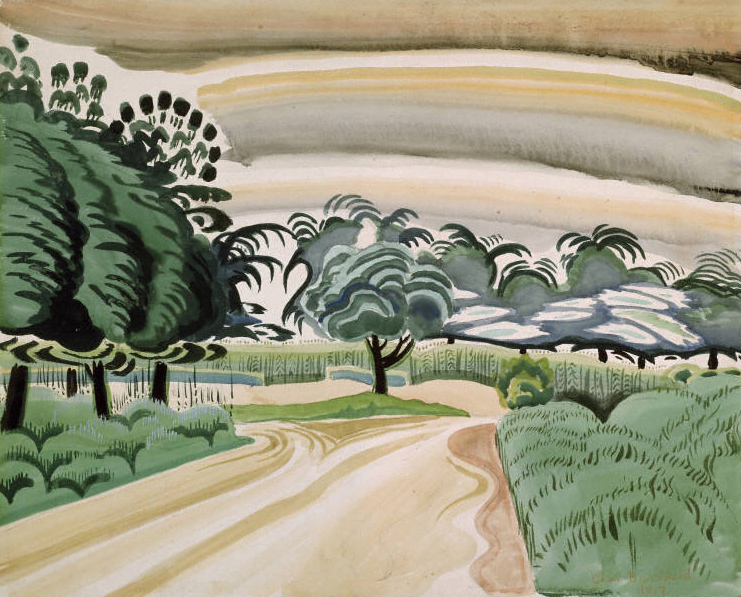

(Left) Charles Burchfield, December Moonrise, 1959. Watercolor on paper, 30 x 36 in. Gift of B. J. and Carol Cutler, 2009. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC (Right) Edouard Manet, Spanish Ballet, 1862. Oil on canvas, 24 x 35 5/8 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1928

One of the hazards pleasures of being a gallery educator at the Phillips is that so many of our visitors are distinguished by their sophistication and knowledge of modern art. I can’t count the number of people who are familiar with the nuances of the relationships between Renoir’s friends in Luncheon of the Boating Party. On one tour of the permanent collection, a gentleman from Argentina told me the precise name of the dance being performed in Manet’s Spanish Ballet. And during Angels, Demons, and Savages, it seemed everyone had either seen the Jackson Pollock biopic with Ed Harris or knew the footage of Jackson himself working in his studio on a canvas on the floor.

Made in the USA is particularly interesting for me because my academic work has been on modernism—European and American. The era between the turn of the 20th century up to World War II is rich in history, experimentation, rule-breaking, and epic attempts to change the world, and all those qualities show in the willful energy of so many of the works in the exhibition.

A standout for me is Charles Burchfield—I have long loved his quivering, ecstatic (and sometimes playful) depictions of nature’s immanence. December Moonrise is an almost over-the-top example of his passionate exaltation of nature as a place of spiritual transcendence. I always stop there on my tours of the exhibition to talk about it. Sometimes I call it the “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” painting. People seem to like it. Thinking about the painting as a place—or a moment—existing in Burchfield’s imagination, I was taken aback when I was told by a tall young man from Canada that far from being an imaginary land/skyscape, the constellations in the sky (which are casting shadows from the moonlight) are true to nature. He pointed out Orion, on the right side, and Corona Borealis, on the left. Apparently these two constellations, visible in northern skies, are only seen together in the month of December. So in fact the painting is a very specific description of nature at a specific time of year.

I can safely say that facts about astronomy are not in my area of expertise, but learning about Burchfield’s respect for the actual sky and stars shining on that December night makes me love his painting even more.

Dena Crosson, Gallery Educator