In the Collection Comparison series, we pair one work from Gauguin to Picasso: Masterworks from Switzerland with a similar work from the Phillips’s own permanent collection.

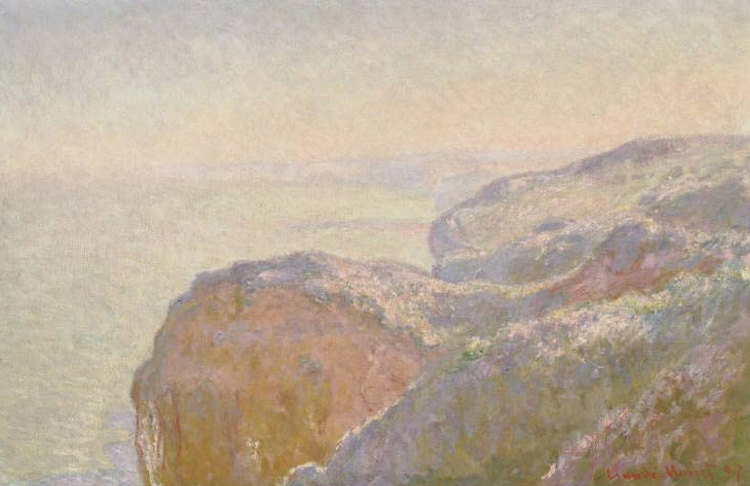

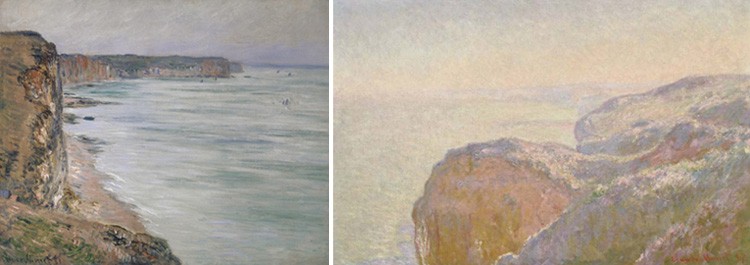

(left) Claude Monet, Calm Weather, Fécamp, 1881. Oil on canvas. The Rudolf Staechelin Collection (right) Monet, Claude, Val-Saint-Nicolas, near Dieppe (Morning), 1897, Oil on canvas 25 1/2 x 39 3/8 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1959

After the death of his first wife, Camille, in 1879, Monet returned to the Normandy coast of France, where he had spent his youth. Currently on view in the Gauguin to Picasso exhibition, Calm Weather, Fécamp records the natural beauty of the coast looking toward Yport. Positioned from a high vantage point and perhaps painted entirely outdoors, it shows Fécamp’s imposing cliffs, which hug the coastline and appear to emerge from the sea at low tide. This work was exhibited in the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition in 1882.

Compare this to the Phillips’s Val-Saint-Nicolas, near Dieppe (Morning) at right above and on view in a nearby gallery in the museum; what similarities or differences do you see? Monet’s Calm Weather, Fécamp was painted in 1881, while Val-Saint-Nicolas, near Dieppe (Morning) was created in 1897. What changes do you notice in the artist’s style?