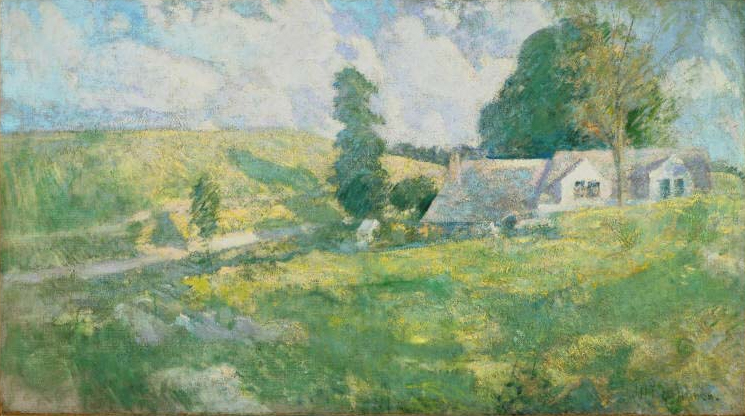

John Henry Twachtman, Summer, late 1890s. Oil on canvas, 30 x 53 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, Acquired 1919

“It’s a pretty painting,” I thought, looking at John Henry Twachtman’s Summer in a first floor gallery at the Phillips.

But no, I couldn’t say just that about a painting. I had to come up with a deeper analysis of it; I had to identify features that pertained to the style of the painter’s period, the symbolism that spoke to the culture of his own time, and the significance it had on the history of art in a bigger picture.

I racked my brain as I struggled to come up with a more specific analysis of the painting, getting closer to the work to capture details.

“The brisk brushstrokes of paint, the interplay of natural light, and the use of bright colors all contribute to the vibrancy to this plein-air painting. The well-blended layers of sky blue and hazy white create soft edges of the sky. As for the symbolism…”

Then I got stuck.

When I’m in a gallery, I often find myself struggling like this to apply academic and stylistic terms to the works. Of course, these are all important components to the general understanding of art history, but was this really what Twachtman was getting at?

“I feel more and more contented with the isolation of country life. To be isolated is a fine thing and we are all then nearer to nature,” Twachtman writes in a letter to fellow artist Julian Weir. Unlike myself, who tried to do an extensive interpretation of the work, Twachtman sought to immerse himself in nature, focusing on the momentary impression of color and light of the landscape.

What’s your first impression of Twachtman’s work? Throw out any words that come to your mind when you see the painting. No need for any fancy, technical terms—”pretty” was all I came up with. After all, it’s not fair that we do a lengthy, grandiloquent interpretation of Twachtman’s work, when what he really wanted to do was share an immediate glimpse of what he saw.

Come visit the Phillips and indulge yourself with Twachtman’s snapshot of the view; the serene colors, natural beauty, or anything about it that catches your eye. Don’t struggle; just marvel.

Summer Park, Marketing & Communications Intern