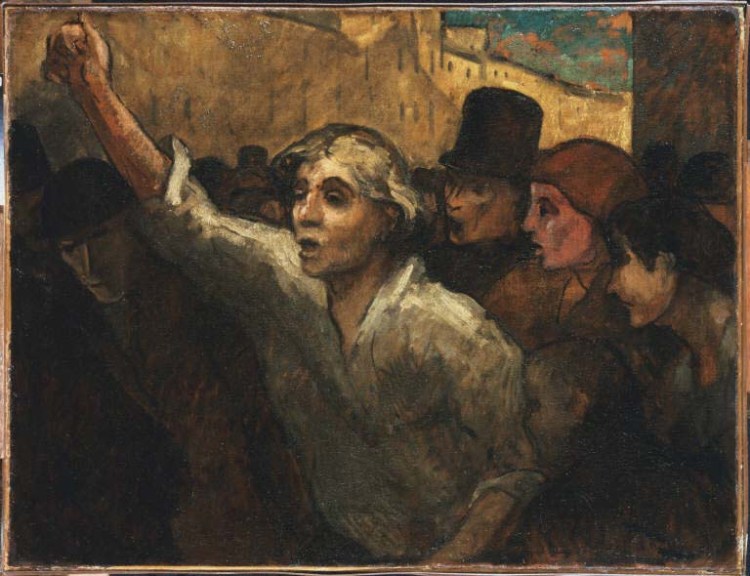

Honoré Daumier, The Uprising, 1848 or later. Oil on canvas, 34 1/2 x 44 1/2 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1925

Given the current political uprisings in Egypt, this week’s Spotlight Talk on Honoré Daumier’s The Uprising (1848 or later) seemed eerily contemporary. The talk, led by Paul Ruther, Manager of Teacher Programs, focused on the timelessness of the work’s subject matter, what Duncan Phillips described as a “symbol of pent up human indignation.”

Paul began by asking members of the group what themes and images they saw in the painting. The desire for change and revolution immediately came to mind, with several participants comparing the imagery presented in the work to that of the current revolutions in Egypt and the Middle East. The painting is thought to portray the 1848 revolution in France and subsequent overthrow of King Louis-Philippe. In the painting, there is a crowd of people all dressed in similarly colored clothing except for one man, the central figure, who, dressed in white, has a raised fist. The crowd is flanked by tall buildings, creating a city-like setting, with only a slight glimpse of sky and sunlight visible at the top right corner of the painting. Paul noted the feeling of claustrophobia present in the painting, which results from Daumier’s use of light and color—while there is apparent sunlight in the painting, the crowd is darkly colored with little to no light being shed on them, helping create this tight, closed-in feeling. Paul explained how Daumier uses the harsh diagonal line of the raised fist that seems almost to try to reach the light above. I noticed how the only person touched by light is the man with the raised fist, and perhaps he is the symbolic representation of social change that the light conveys.

Many art historians during Daumier’s time considered this work “unfinished,” because of the lack of dark coloring at the base of the image. One tour attendee brought up the idea that perhaps Daumier created an impressionist-style painting years before his time!

And, because it is always nice to end with a Phillips connection tidbit, this work was not publicly displayed until Duncan Phillips purchased it in 1925. Phillips referred to it as the “greatest painting in the Collection.”

Hannah Hoffmann, Marketing Intern