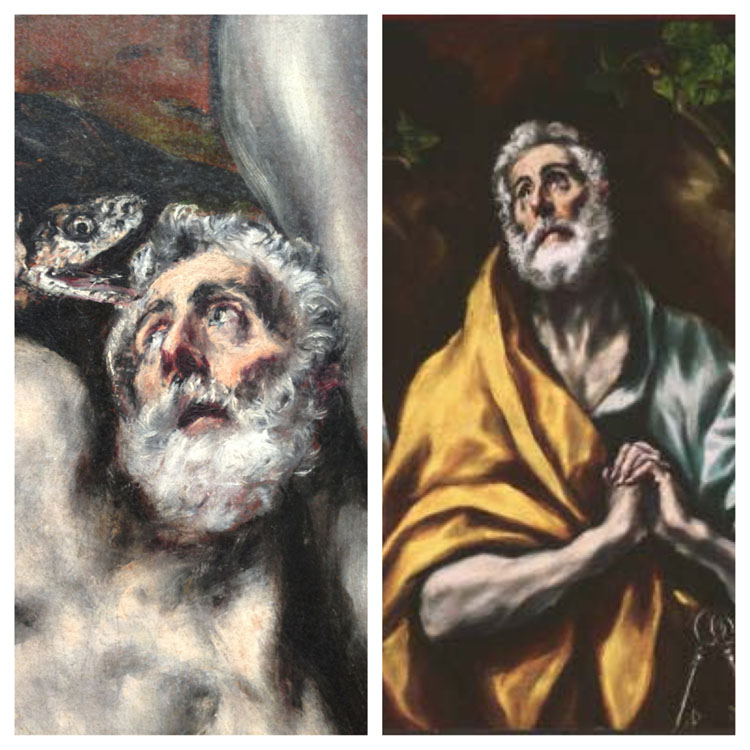

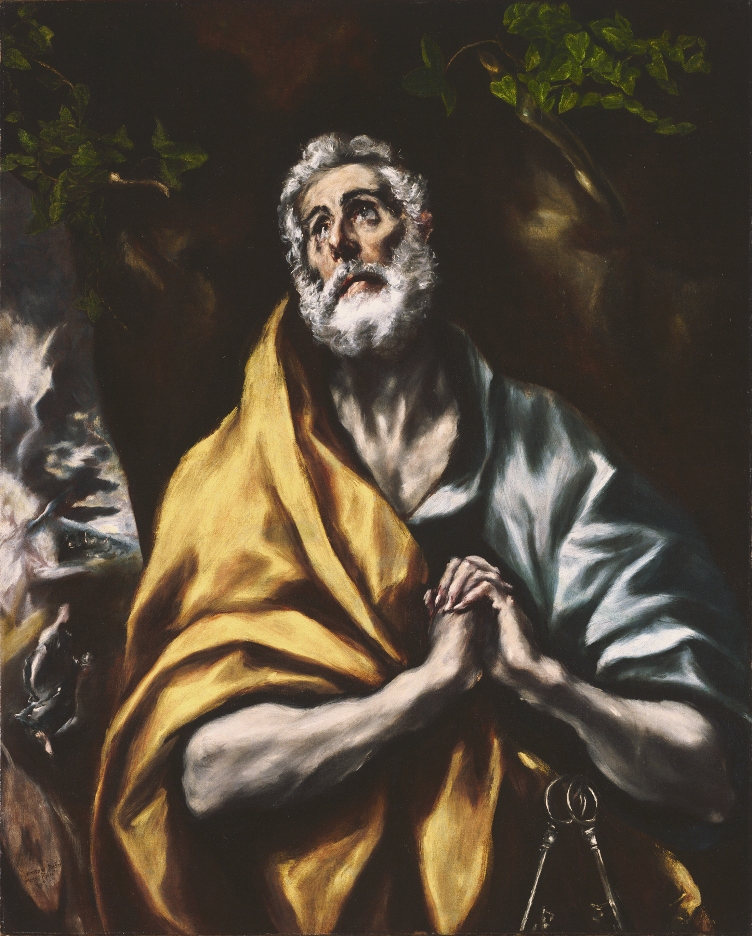

El Greco, The Repentant St. Peter, between 1600 and 1614. Oil on canvas,

36 7/8 x 29 5/8 in. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1922

Baltimore-based artist Bernard Hildebrandt gives El Greco’s The Repentant St. Peter (1600-1614) a face lift (literally) in the new Intersections project at The Phillips Collection. Two things about this project are interesting to me: the sound that echoes across the room and the placement of the art work. The sound to me is like a low growl emanating from St. Peter’s mouth, an agonized groan. It is mesmerizing. Moreover, the work is shown in low lighting, giving the room an eerie atmosphere. The project sits right in the middle of the permanent collection. Just around the corner is the cheerful Luncheon of the Boating Party (1880-81) by Renoir.

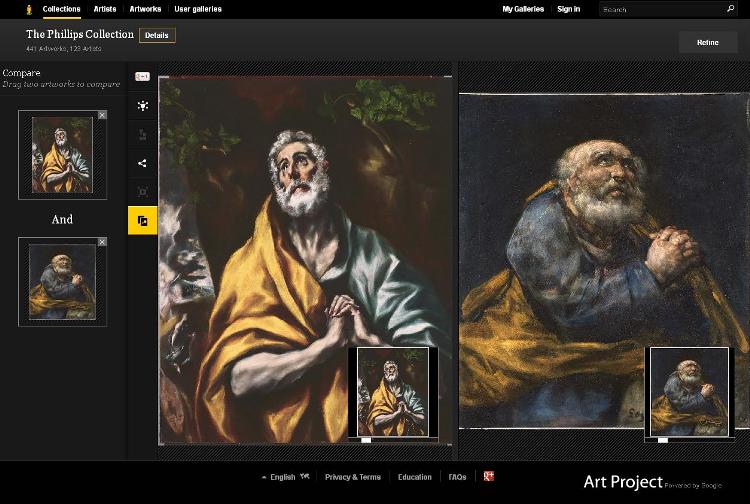

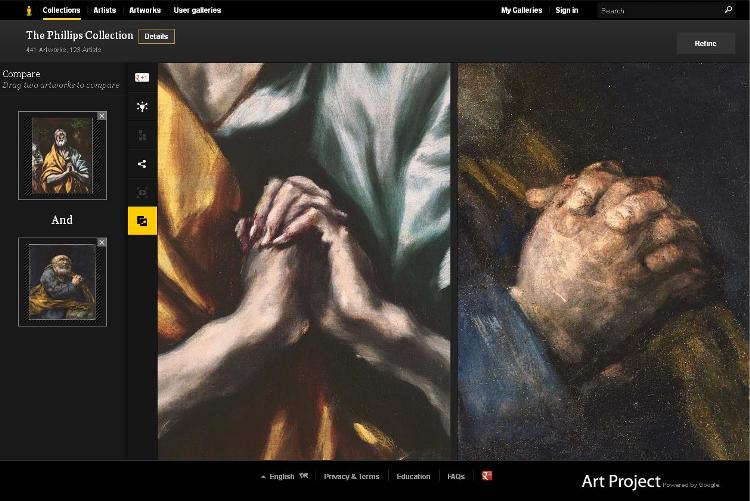

El Greco was recalling the traditions of Byzantium icon paintings with his up-close view of the holy man’s face, but in the then-contemporary Baroque style depicting high drama and emotion. Hildebrandt brings El Greco’s work into the 21st century by converting a series of images into a new medium–video.

We will have a chance to hear more from Hildebrandt about the process behind his work in an Artist’s Perspective talk this Saturday, July 20, at 3 pm. I wonder what El Greco would have thought of the intersection?

Jane Clifford, Marketing Intern