A small installation of works on paper by Ellsworth Kelly was recently installed in conjunction with Ellsworth Kelly: Panel Paintings 2004-2009, currently on view through September 22. Included in these works is a small maquette by Kelly, done in preparation for a 2004 sculpture commissioned by the Phillips, shown below.

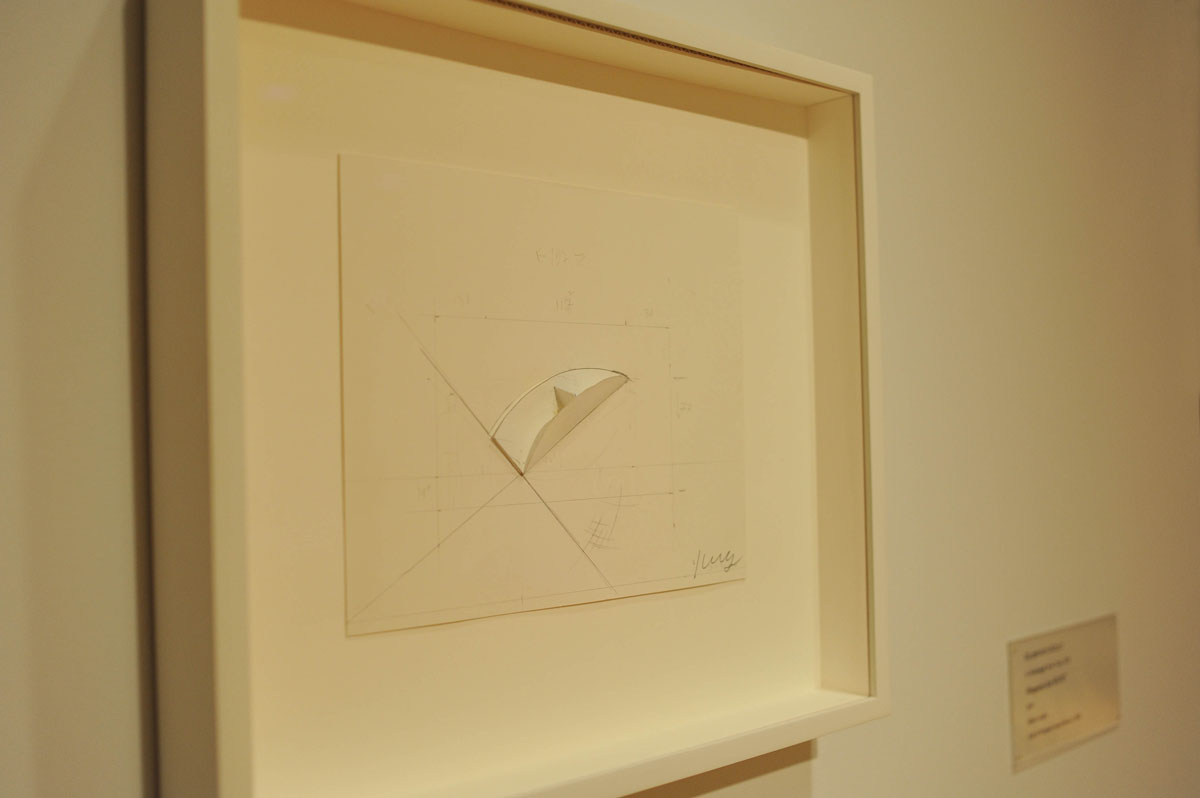

Installation view of Ellsworth Kelly’s Maquette for EK 927, 2005. Mixed media, 9 x 11 x 5/8 in. (22.9 x 27.9 x 1.6 cm). The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C., Acquired 2006. Photo: Joshua Navarro

To commemorate the new courtyard opening in 2006, The Phillips Collection commissioned Kelly to create a sculpture specifically conceived for the museum’s new courtyard as a gift of Phillips Trustee Margaret Stuart Hunter. Mounted at an unusual angle, Untitled (EK 927) (pictured below) is a large-scale bronze curve, perched elegantly on the west wall of the Hunter Courtyard. It reflects Kelly’s enduring interest in uncovering the reductive essentials in natural forms. There is a timeless and mysterious quality to the sculpture—a simple form of line, volume, and shadow that seems to defy gravity.

Ellsworth Kelly, Untitled (EK 927), 2005. Bronze. 17 in x 63 3/16 in x 1 in (297.2 x 160.5 x 2.5 cm). Commissioned in honor of Alice and Pamela Creighton, beloved daughters of Margaret Stuart Hunter, 2006. Photo: Lee Stalsworth

The sculpture and its corresponding maquette were both accessioned into the collection in 2006. You may be asking why the Phillips decided to acquire the model Kelly made for the sculpture and accession it into the collection as a work of art in itself. Maquettes, by nature, are simply stand-ins for the real thing, and are frequently discarded once the installation of art is complete. When they are created by an artist, however, maquettes reveal much about the artistic process involved in creating a larger-scale work. This particular maquette was presented in 2006 to then-director Jay Gates and Ms. Hunter by Kelly himself, who was at the museum overseeing the installation of the sculpture, as a gift in honor of the collaboration. Accessioning the maquette into the collection was a conscious decision by staff to highlight Kelly’s creative process and the personal relationship between Kelly and the Phillips. As we honor Kelly during the year of his 90th birthday, we wanted to emphasize our history with the prolific artist and shed light on the process behind one of our most important works by featuring the maquette alongside the fully-realized works currently on display.

On a side note, this isn’t the only time a maquette for a sculpture has been accessioned into the museum’s collection. In 2012, a model for Seymour Lipton’s Oracle (1966), a bronze and Monel sculpture at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, was accessioned into our permanent collection. Lipton is well represented at the Phillips with sculpture and drawings, but this model was an important acquisition to the curatorial team as it reveals the artistic intent behind a finished product, as well as draws interesting comparisons to other works by the artist in our collection.