It’s a two-for-Thursday here on the blog, as we enter day four in our celebration of FotoWeekDC. Both of the images we’re featuring today from Shaping a Modern Identity: Portraits from the Joseph and Charlotte Lichtenberg Collection stem from photographers who worked for the Farm Security Administration, documenting the federal government’s efforts to restore rural communities affected by the Great Depression. The similarities between the two images, however, end there.

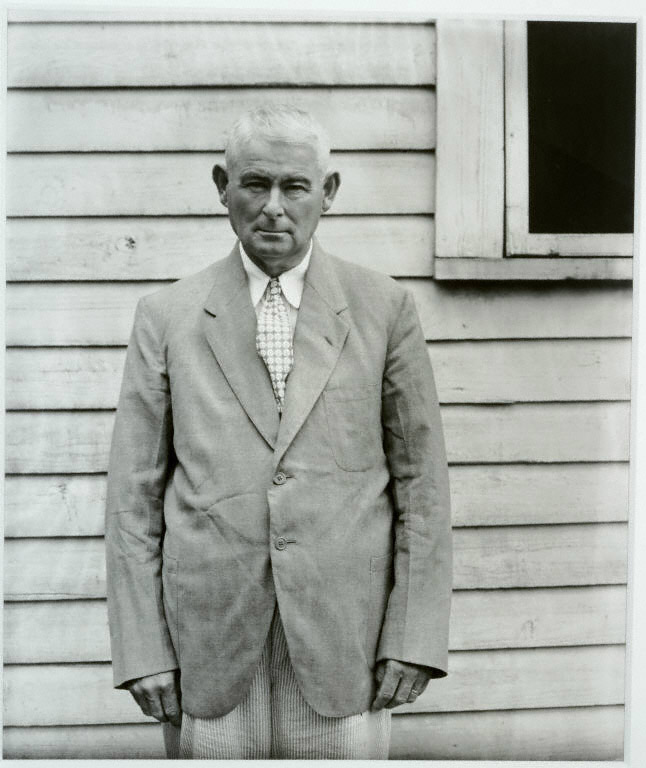

Walker Evans, Landowner, Moundville, AL, 1936. Gelatin silver print. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C., The Joseph and Charlotte Lichtenberg Collection, Partial and promised gift of Joseph and Charlotte Lichtenberg, 2005.

Walker Evans’s photographs went beyond the intentions of the FSA’s agenda, as he sought to capture the essence of the true consequences of the Depression on ordinary American life. In the summer of 1936, Evans took a leave from the FSA to work independently with writer James Agee to capture the people and scenery of Moundville, Alabama. In his portrait Landowner, Moundville, AL we see a man standing in front of the siding of a building, looking straight into the camera in an expressionless manner, his arms casually at his sides. Evans portrays him as an archetype of those affected by the Depression: his wrinkled suit, the lack of emotion, the low contrast between the man and the background, all suggest the everyday struggles of any man in the subject’s situation. In this depiction, Evans isolates the subject from the glorification which often accompanies portraiture (as seen in Serrano’s depiction of “Sir Leonard”) and approaches his subject as the everyman. He does little to explore him emotionally but rather presents a frank image with somber undertones of the impending economic circumstances of the time.

Jack Delano, Bootleg Coal Miner near Pottsville, PA, 1938. Gelatin silver print. Joseph and Charlotte Lichtenberg Collection.

On the other hand, Jack Delano sought to personally connect with his subject matter, carefully composing his images to highlight what sets his subject matter apart, individualizing them. “To do justice to the subject has always been my main concern,” he wrote in his autobiography published in 1997. “Light, color, texture and so on are, to me, important only as they contribute to the honest portrayal of what is in front of the camera, not as ends in themselves.” In 1938, Delano spent a month living amongst and photographing the men at a mine in eastern Pennsylvania and due to this constant proximity with his subject matter, his photographs demonstrate a special connection with and compassion for the miners. In Bootleg Coal Miner near Pottsville, PA, the subject appears scruffy and worn, his mouth is open revealing missing teeth, and a cigarette rests on his lower lip. The photographer has cropped the man’s face tightly within the frame as the miner extends diagonally across the composition. This is no everyman; he has a definite identity. While Evans’ subject in Landowner seems to blend into the background and thus becomes more of an idea or archetype than an actual person, Delano’s miner confronts the viewer head-on, declaring himself an individual, albeit one of many struggling to make ends meet in tough economic times.