John Cage seems to be everywhere. The Phillips participated in a city-wide centennial event back in September, one of many happening around the world. My Modern and Contemporary Poetry class from Coursera spent some serious time learning about Cage’s chance operations in poetry, generating passionate discussion online between people all over the globe. Our Duncan Phillips lecture by Rick Moody centered on Cage’s composition “4:33″. And yesterday came news that the Museum of Modern Art has acquired “4:33″, the score comprised of “just three folded sheets of almost blank onionskin paper”. If you’ve not experienced Cage’s “4:33″, the clip below demonstrates the fascination and awe over the surprising piece. [jwplayer config=”Single Video” mediaid=”14178″]

Tag Archives: John Cage

Listening to Rothko

In a stimulating Duncan Phillips Lecture, “John Cage and the Question of Genre,” which served as a keynote to this year’s International Forum Weekend dedicated to the confluence of art and music, the novelist and musician Rick Moody praised Cage’s chance works, such as his ineffable composition 4’33”, as a “a breath of fresh air in the midst of bourgeois individualism.” According to Moody, Cage disregarded any notion of genre in favor of “creative work whose primary intention is simply that it is creative, so that it might simply give a name to creativity itself.” 4’ 33”, first performed in 1952, was designated by Cage as a “composition for any instrument (or combination of instruments).” It consists solely of potential sound: the random noise that occurs during the duration of its “silent” performance.

Halfway through, Moody intermitted his lecture with a cunning act of bravura by playing the sounds of paintings and photographs he recorded in various museums with his iPhone: the incidental noises created by the crowds moving past them.

Afterwards, Moody took me aside and asked if he might be able to spend a few minutes in the Rothko Room in order to record the sound of Rothko’s paintings. I happily obliged, and we both intently listened to the paintings. Rothko may have approved: he once compared his paintings to the voices in an opera. And for a moment, ever so faintly, I thought I heard Rothko’s beloved Mozart emerge from the depth of the silence in the room.

Six Degrees of Separation: A Tour

1˚CAGE

Start your visit on the 2nd floor of The Phillips Collection, outside the Rothko Room, and discover watercolors by John Cage. Primarily known as an avant-garde composer, Cage turned the sounds of an audience’s awkward, ambient shuffling into music. (Return to the museum at 4 pm on September 6 for a full Cage experience, as part of the John Cage Centennial Festival, starting with a panel discussion on Cage’s work and collaborations, including his friendship with Jasper Johns, and culminating with a performance by Irvine Arditti of the impossible-to-perform Freeman Etudes for solo violin.)

2˚JOHNS

Continue up the curving stairway to special exhibition Jasper Johns: Variations on a Theme, and you’ll find prints by Johns that share in Cage’s sense of humor. Johns too makes art out of his audience in works like High School Days (1969), a lead embossed shoe of the kind that lends a naughty view when strategically polished and placed beneath a woman’s skirt. Johns has embedded a mirror in the toe so the curious viewer glimpses only his or her own eye. He made this innovative lead relief and others at Los Angeles print publisher Gemini G.E.L. Towards the end of the exhibition look for Ocean (1994), a lithograph of a dancer leaping over abstracted map forms. The dancer is none other than Merce Cunnningham, the avant-garde choreographer who was also a friend to Johns and Cage.

3˚STELLA

In 1967, Frank Stella designed a set and costumes for a dance piece by Cunningham named Scramble. That same year, he created his first prints and, like Johns, collaborated with Gemini G.E.L. In one print made that year, Marriage of Reason and Squalor, Stella revisited his iconic 1959 black painting. Walk from the Johns exhibition into the original Phillips house, through the Main Gallery, down a few steps, and past the Klees, and you’ll find Stella’s small work on paper, which was gifted to the Phillips in 1991.

4˚VILLAREAL

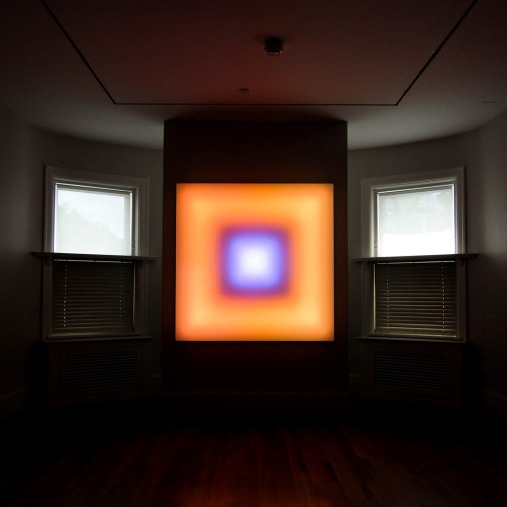

A luminous glow beckons you beyond Stella’s print, into a gallery with a fireplace, a single bench, and a solitary 60″ x 60″ (but digitally infinite) artwork. Scramble (2011) is Leo Villareal’s response to a conversation he shared with Frank Stella as part of a panel discussion on Kandinsky at the Phillips the previous year. Sharing a name with Stella’s Cunningham collaboration, this work reminds of motion and dance with LEDs relentlessly shifting (and never repeating) their patterns of color. Visitors remark that the contemporary color field is like millions of digital Rothkos.

5˚ROTHKO

With your mind thus saturated (and somewhat scrambled), you may now be craving a respite in the Rothko Room. Wind your way back to the 2nd floor of the Goh Annex, where you began with Cage, and enter the small chamber which is also appointed with a single bench (that was the artist’s idea). The Rothko Room is always there for you. (The permanent, meditative installation inspired a new commission, something to look forward to next year, but for now the scent of beeswax remains absent from your tour.)

6˚KELLY

Turn left out of the Rothko Room toward a stairway and red wall. Pause on the landing and look out the window. Straight ahead, on the far wall of the courtyard, floats Ellsworth Kelly’s swooping untitled bronze. Villareal’s recent body of work includes a Kelly-inspired piece, Coded Spectrum, in addition to his work in conversation with Stella.

Cecilia Wichmann, Publicity and Marketing Manager