Curator at Large Klaus Ottmann is author of The Essential Mark Rothko. He’ll share his insights on the artist in a lecture tomorrow evening. Rothko is getting the spotlight in D.C. this season with John Logan’s Tony® Award winning play Red at Arena Stage. In anticipation, Klaus recently sat down with Phillips Communications Director Ann Greer to talk all things Rothko. The interview will be published in Arena Stage’s program book. Read a preview here.

Ann: Why do you think Mark Rothko looms so large in the ranks of 20th century artists?

Klaus: He was a unique artist in the way he dealt with color. He was very deeply involved in philosophy, religion, and he had an unusual ability to make his paintings communicate with the public. It was a well-known fact that people used to burst out in tears in front of his paintings, many times. I think he had a very emotional and very deep effect on the viewer – one very few artists have been able to have.

Ann: How do you think that sort of “alchemy”–if I can use that word–how does that happen?

Klaus: Well, of course, it didn’t happen overnight, he developed slowly into it. But, I think a lot of it has to do with the fact that he was deeply religious, he was very philosophical. It had to do with the fact that he very strongly believed that his paintings should communicate–that there was a dialogue going on. It has also to do with his background in theater, he always wanted to become an actor, and he believed his works to be plays, he believed his works were created to be emotional conversations with the viewer–similar to what a play can do . . .

. . . he kept thinking about the three dimensional space. That’s something I think is very important. It’s very clear to me when I sit in the Rothko Room at The Phillips Collection.

Ann: Of course, Klaus is talking about the Rothko Room at The Phillips Collection, which was actually the first public space devoted exclusively to work by Rothko. Rothko was very involved with Duncan Phillips in planning the dimensions, the light levels, the bench.

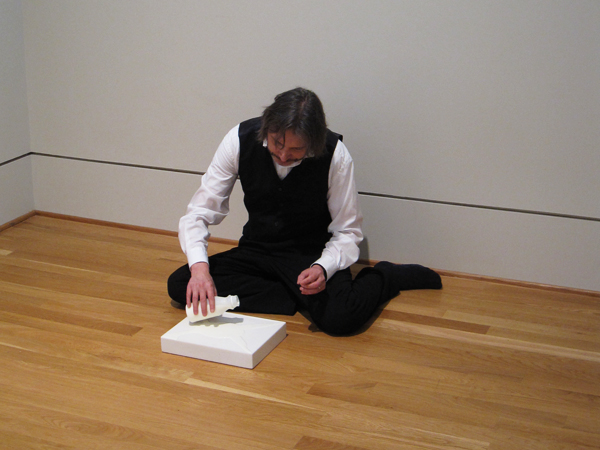

Klaus: There you are very close to the paintings, there are four paintings, one on each wall of the room, you are surrounded by them. You sit on the bench that Rothko put in the room, and you can feel the presence of the paintings. It’s not just an optical, visual presence, but an emotional presence. This is what he always wanted. He wanted the paint to come out and almost hover in the space in front of you and to touch you. So, he was always thinking of this three dimensional space like a stage. In a way, the Rothko Room is almost like a stage with four sides–you are in it and a part of it, and you are interacting with the other actors; you become part of that emotional play that he created. So, he never gave up that idea; the theater was always there, and it was always the framework that he used to conceptualize and make his art. To me, that’s very, very important.