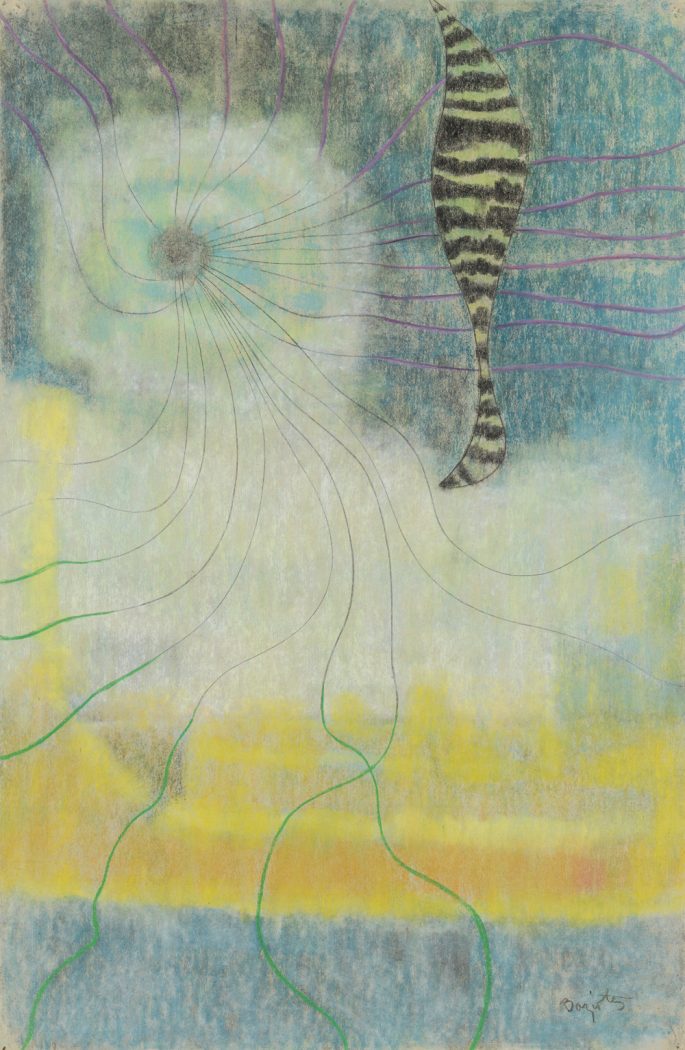

“My last show of symbol paintings are just Klee blown-up large.”—Gene Davis

Gene Davis acknowledged the profound impact of Paul Klee—“his very first mentor”—on his artistic development. Beginning in the 1940s, Davis made regular visits to “the Klee room” at the Phillips, where Klee’s small masterpieces left an “unforgettable impression.” These untitled works by Davis with playful, flat forms were among a series of symbol paintings the artist made at the end of his life that harken back to his early experiments of the 1950s, when he painted freehand compositions with organic motifs (for example, Black Flowers). Davis attributed his “urge to do whimsical, free-hand drawings” to his “early infatuation with Paul Klee and children’s art.” Like Klee, Davis valued spontaneity and intuition over intellect—aspects that lay at the heart of Davis’s artistic methods, whether in his stripe paintings (such as Red Devil) or in his more gestural works.

This work is on view in Ten Americans: After Paul Klee through May 6, 2018.