Read part one of Jenna’s remembrance of James McLaughlin and history of the staff show here.

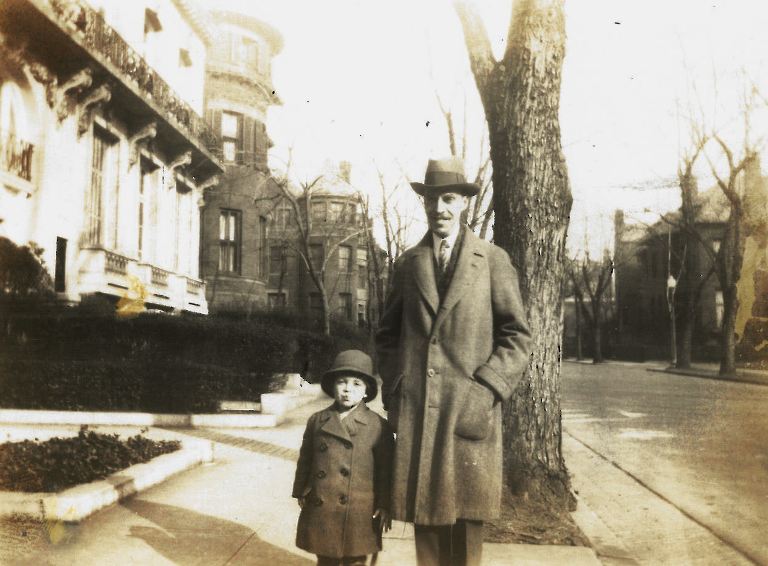

James McLaughlin with a group of young museum-goers, holding Marjorie Phillips's painting, Night Baseball. Photo courtesy Phillips Collection Archives.

Duncan and Marjorie Phillips’s son Laughlin described his fondness for James McLaughlin and his character at McLaughlin’s 1982 memorial service:

Jim was in many ways my mentor. When he first came to the Collection, he was 24 and I was 9. I didn’t come to the gallery much those days. But, during summer visits to our family home in Pennsylvania, he taught me about the woods and the mountains, and how to mix paints, and hammer a nail and throw a curve. His enthusiasms were legion and irresistible.

My mother and I feel a great personal loss and a great loss to the Collection. Jim knew every painting here. Every nook and cranny of the building. He approached his work with the creative spirit and sensibilities of an artist – never those of a museum bureaucrat.

He was fiercely loyal to the Collection and proud of it. And well he might be, because everything here has been under his care, for 49 years.

Jim was the sort of a person we would all like to be, but aren’t. He was a man of principle and deep conviction. Strong, and yet extraordinarily sensitive. A gentleman. Independent and able.

The personal memories and anecdotes shared by Phillips staff that knew him make McLaughlin a legendary figure in the museum’s history. According to Alec MacKaye, McLaughlin built and carved many wooden frames specifically for paintings included in The Phillips Collection. Beyond the walls of the Phillips, Bill Koberg recalls that McLaughlin built his own house. Koberg, a preparator here for 40 years, worked closely with and learned from McLaughlin.

Through McLaughlin’s memory and legacy of a staff show, The Phillips Collection continues to cultivate the artistic community that McLaughlin encouraged and esteemed during his lifetime.

Jenna Kowalke-Jones, Young Artists Exhibitions Program Coordinator