Each week for the duration of the exhibition, we’ll focus on one work of art from Toulouse-Lautrec Illustrates the Belle Époque, on view Feb. 4 through April 30, 2017.

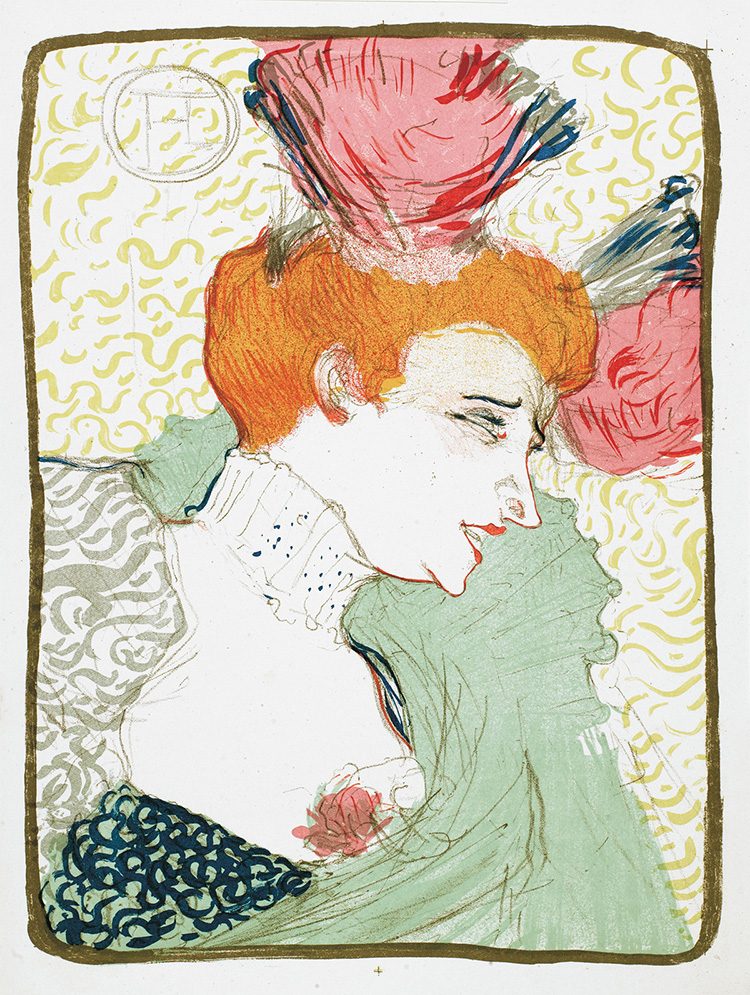

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Mademoiselle Marcelle Lender, Half-length, 1895. Crayon, brush, and spatter lithograph, printed in eight colors. Key stone printed in olive green, color stones in yellow, red, dark pink, turquoise-green, blue, gray, and yellow-green on wove paper. State IV/IV, 12 15⁄16 × 9 5⁄8 in. Private collection

Marcelle Lender found fame as Galswinthe in Hervé’s operetta Chilpéric, revived by the Théâtre de Variétés in 1895. Toulouse-Lautrec attended 20 performances, making sketches from the audience. He immortalized the red-headed actress in the painting Marcelle Lender Dancing the Bolero in Chilpéric and in 13 prints. After developing sketches and trial proofs for this lithograph, Toulouse-Lautrec worked closely with master printer Henri Stern at Ancourt to manage its production in four editions. Printed in eight colors from eight separate stones, it stands as proof of Toulouse-Lautrec’s mastery of lithography. Its fourth state, seen here, was reproduced in the influential German art magazine Pan. Its reference to performance, make-up, costumes, and stylish coiffures shows the influence of Japanese prints like Moatside Prostitute by Utamaro.