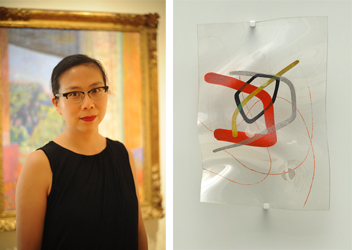

(Left) Joyce Tsai, Photo: Joshua Navarro. (Right) László Moholy-Nagy, B-10 Space Modulator, 1942. Oil on incised and molded Plexiglas, mounted with chromium clamps on painted plywood, Plexiglas: 17 3/4 × 12 inches (45.1 × 30.5 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection 47.1063 © 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Joyce Tsai will be giving a talk, “Modulating Modernism“, tonight at 6:30 at our Center for the Study of Modern Art.

László Moholy-Nagy’s Space Modulators (a great example at the Guggenheim, right), executed late in his career, are beautiful, but slightly odd painting/sculpture hybrids made in clear plastic. I came across them while I was researching his oeuvre for my book, Painting after Photography, and was drawn to them because they look so radically different from the photography and rigorous, geometrical abstract painting he made at the Bauhaus. These late works on plastic are biomorphic, replete with undulating curves and are difficult to categorize for all sorts of reason. They’re materially fragile, prone to damage, and age unpredictably. The more I worked on these objects, the more I began to see how important they were to the artist, how much they sought to synthesize his life’s work.

Joyce Tsai, 2013-2014 Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center for the Study of Modern Art and the George Washington University