Each week for the duration of the exhibition, we’ll focus on one work of art from Toulouse-Lautrec Illustrates the Belle Époque, on view Feb. 4 through April 30, 2017.

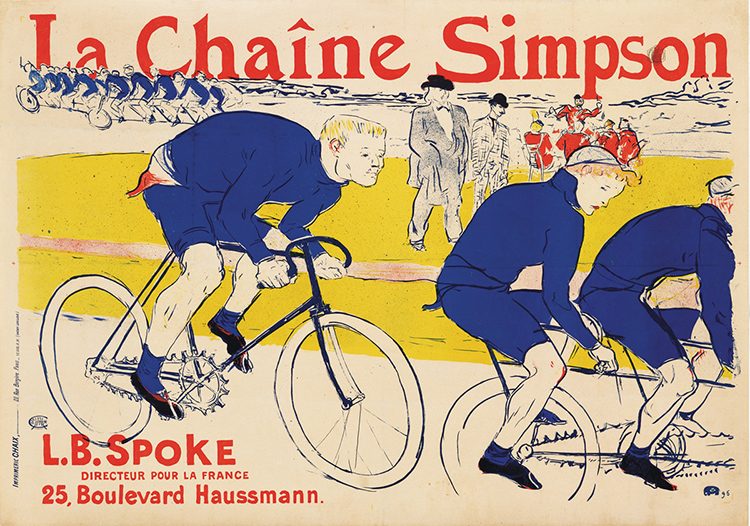

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, The Simpson Chain, 1896. Brush, crayon, and spatter lithograph, printed in three colors. Key stone printed in blue, color stones in red and yellow on wove paper, 32 5⁄8 × 47 1/4 in. Private Collection

Following the invention of the pneumatic tire in 1888, cycling became a fashionable, modern-day sport. Competitive cyclists raced at Vélodrome Buffalo and Vélodrome de la Seine on Sunday afternoons, with Toulouse-Lautrec in attendance. In 1896, Louis Bouglé, the French representative of the English Simpson cycling company, commissioned Cycle Michael, which advertises a bicycle chain. Bouglé also managed Welsh racing champion Jimmy Michael, shown here sucking a toothpick as he is timed by trainer “Choppy” Warburton.

Bouglé rejected the poster design due to the inaccurate rendering of the chain product. Toulouse-Lautrec printed 200 impressions in olive-green for cycling fans.

The Simpson Chain—Toulouse-Lautrec’s second attempt at the Simpson cycling company’s commission—was a success. For this work, he accurately depicted the chain and infused the scene with dozens of cyclists zipping around the track, their blurring wheels creating the effect of speed. French cyclist Constant Huret follows two pacing riders, the first partially cropped to reinforce movement. In the center of the ring stand Bouglé and company owner William Spears Simpson.