Each week for the duration of the exhibition, we’ll focus on one work of art from Toulouse-Lautrec Illustrates the Belle Époque, on view Feb. 4 through April 30, 2017.

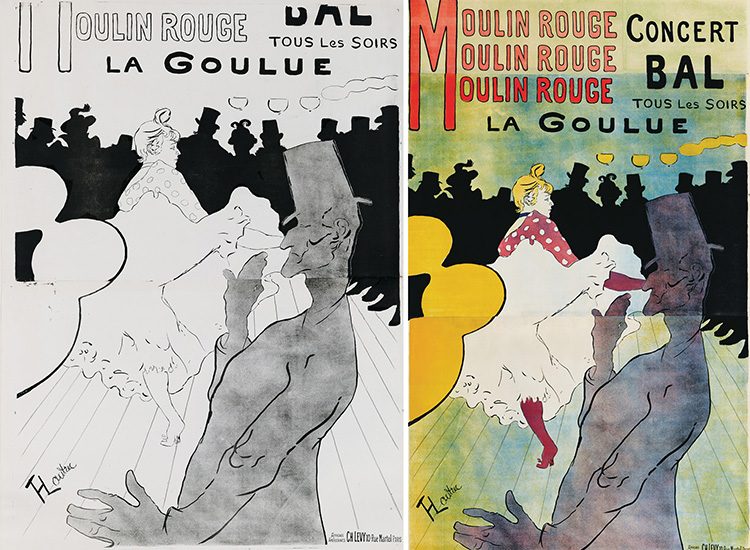

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (left) Moulin Rouge, La Goulue, 1891. Brush and spatter lithograph, printed in black on two sheets of wove paper. Trial proof, 65 3/4 × 46 7⁄16 in. Private collection (right) Moulin Rouge, La Goulue, 1891. Brush and spatter lithograph, printed in four colors. Key stone printed in black, color stones in yellow, red, and blue on three sheets of wove paper, 75 3⁄16 × 46 1⁄6 in. Private collection

The newspapers have been very kind to our offspring. I’m sending you a clipping written in honey ground in incense. My poster has been a success on the walls.—Toulouse-Lautrec to his mother, 1891

Toulouse-Lautrec’s first attempt at printmaking was this poster used to advertise Montmartre’s entertainment hotspot. With it, he innovatively transformed an image drawn from popular culture into an iconic work of art marked by its modernity. It was the first to feature a star attraction, dancer La Goulue (The Glutton) who took erotic provocation to the extreme, delighting audiences with the chahut, a vigorous cancan. She was described in Le Figaro Illustré as “bending her body so much to convince you she was about to break in half, the folds of her dress were on fire.”

For the poster, Toulouse-Lautrec created sketches and a nearly full-size drawing. He transferred the image onto the lithographic stone with brush and crayon, and worked closely with printers to correct proofs produced from four separately inked stones. Due to its size, the work was printed on three sheets of paper. The nuanced tone of dance partner Valentin le Désossé (The Boneless), the figure in the foreground, was achieved through an inventive spatter technique. The silhouetted onlookers include the artist’s cousin Gabriel Tapié de Céleyran, dancer Jane Avril, artist William Warrener, and others. A unique trial proof in black and white (with the essential design) and an extremely rare version of the poster (before final lettering) are presented here. Comparing the images shows Toulouse-Lautrec’s inventive use of color and design to highlight the dizzying atmosphere of the cabaret and to accentuate the hair and dress of La Goulue. The performer’s most alluring traits (her risqué style and notorious legs) are emphasized in a larger-than-life-size work that secured her celebrity and brought Toulouse-Lautrec fame.

This poster stunned the public when it premiered in some 3,000 impressions throughout Paris. Artist Francis Jourdain recalled, “the shock…. This highly original poster, was, I remembered, carried along the Avenue de l’Opera on a kind of small cart, and I was so enchanted that I walked alongside it.” Critic Félix Fénéon declared posters to be “real art, by God! and it cries out, it’s part of life itself, it’s art that doesn’t fool around and real guys can get it.”