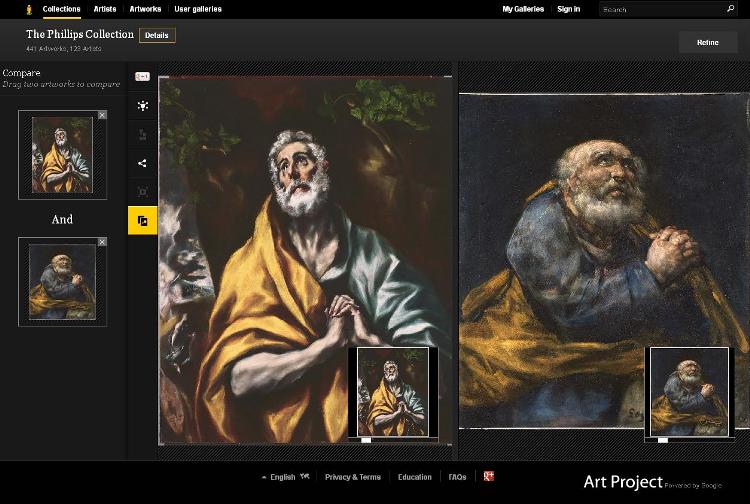

“Flame and Stone”–that’s how Duncan Phillips summed up The Repentant St. Peter by El Greco (1600-1605) and The Repentant St. Peter by Goya (1820-1824), respectively. Mr. Phillips loved comparing the two renderings of the saint, and their current side-by-side display in the Music Room (and in this Google Art Project comparison) reflects this tradition. As a graduate intern in the education department, I’ve led some of The Phillips Collection’s weekday noon spotlight talks. Having lived in Spain for a year and a half, I was immediately drawn to the work of Goya and El Greco, who lived and worked in Madrid and Toledo nearly 200 years apart. I thought their two versions of Saint Peter would make an excellent spotlight.

When giving a gallery talk on Goya’s The Repentant St. Peter, I often start by asking visitors to imagine the work as a movie poster and create a corresponding film title. I’ve received answers ranging from Dear God, Please Forgive Me! to Please Let Me Win the Lottery! Thinking about Goya’s canvas as a movie poster transforms this initially bleak and lackluster painting into an intensely-personal rendering of a man desperate for visitors. We discuss the way the dark, nondescript background and the modern cropping—similar to a close-up film shot—add to the poignancy of the image.

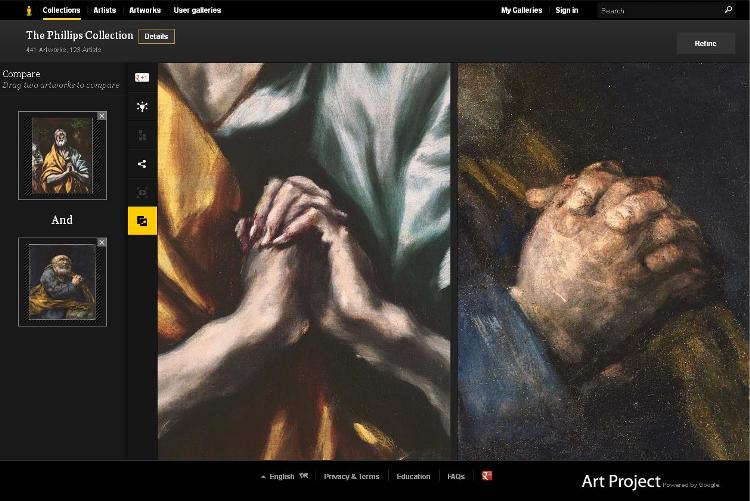

Visitors often shift the conversation to compare Goya’s painting with El Greco’s representation of the same subject without my prompting. Frequently, they remark on the icy quality of the light in El Greco’s canvas as well as the more “holy” and idealized appearance of his St. Peter. Goya’s St. Peter, they usually observe, looks more like a “grubby fisherman—a guy who works with his hands.” St. Peter’s hands are a recurring point of discussion. In comparison to the elegantly elongated fingers in El Greco’s painting, visitors note the stubby, tightly-clasped fingers of Goya’s St. Peter, stepping in for a closer look when they learn that Goya returned to the painting to shorten the fingers, a process which has left a visible trace. It’s wonderful to see how, so many years after Duncan Phillips first hung these paintings side by side, they continue to inspire conversations.

Kristin Enright, Graduate Intern for Programs and Lectures